In the summer of 1814, the fledgling U.S. republic was on the brink of a catastrophe, one that would test its resiliency as a nation and its ability to sustain its sovereignty and independence for the long haul. The war that it declared on Great Britain two years earlier, with considerable enthusiasm, was proving to be a debacle. Many of the strategic assumptions that underpinned the U.S. march to war were erroneous, while poor military leadership, a lack of professional soldiers and an overall shortage of supplies and equipment led to defeat after defeat. With each passing setback, opposition to the war increased and there was growing talk of secession amongst the New England states who were always opposed to what they called “Mr. Madison’s War.”

By July 1814, American fortunes had taken another turn for the worse. For two years the British regarded the conflict with the United States as a side show while they battled Napoleon for mastery of Europe. Consequently the American war was fought with whatever money, manpower and naval force that could be spared. With Napoleon’s defeat and subsequent exile in May, the British were now able to shift their focus. Thousands of battle-hardened redcoats began arriving in the Chesapeake ready to strike a decisive blow. By the end of August, the American capital of Washington D.C. would be in flames and the entire American experiment under siege.

The March to War

The War of 1812 is perhaps one of the least known and least understood wars in American history. It is the United States first war, post-independence, and one the country was ill-prepared to fight. It is a conflict that seems as if it could have and should have been avoided. Understanding the reasons and rationale for the war and how and why the decision to declare war was made are critical for appreciating how the United States found itself in such a terrible predicament in the Summer of 1814.

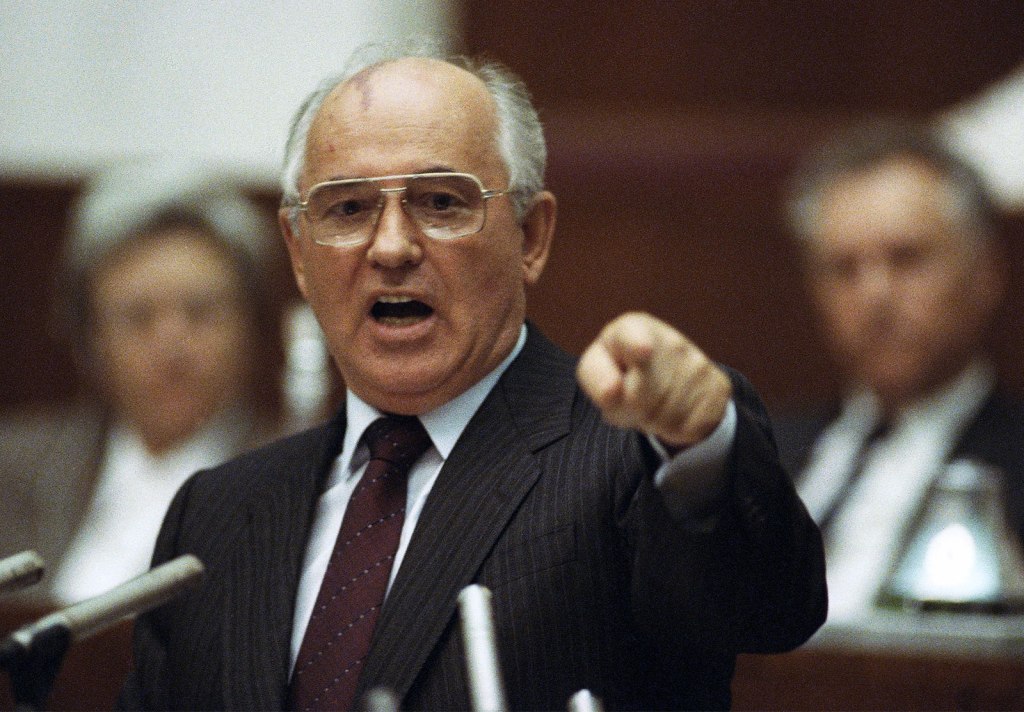

The United States declared war on Great Britain on June 18, 1812. Anti-British sentiment in the country had reached a fevered pitch by this time and there were strong voices, including that of President James Madison, clamoring for war. Other officials, mostly Federalists from New England that benefited from trade with Britain, were less enthusiastic. In his call to arms, Madison presented a detailed summary of hostile British conduct towards the United States denouncing the practice of impressment and Great Britain’s continued harassment of U.S. shipping. He also accused the British of inciting Indian attacks on frontier settlements in the Great Lakes region and Mississippi territories. In the end Madison and the War Hawks argued that Great Britain forced the United States to either surrender its independence or maintain it by war. One prominent War Hawk, Congressman Felix Grundy from a Tennessee declared that he would rather have war than further “submit” to British insults.

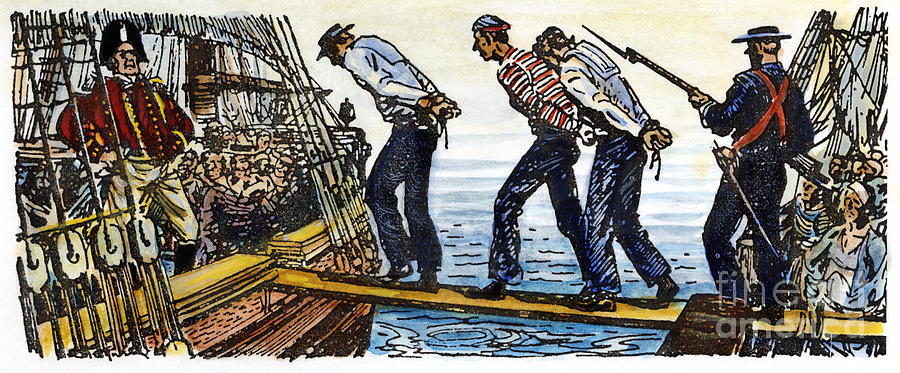

Of all the causes of the war, the British practice of impressment was the most important and most vexing for America. Great Britain’s ongoing war with Napoleon put increased manpower demands on the Royal Navy. Unable to meet these quotas through voluntary enlistments, the Royal Navy resorted to impressment. For almost a decade the United States suffered the ignominy of having its neutral merchant ships boarded by the Royal Navy and crew members suspected of being British subjects removed and forced to serve on British ships of war. According to estimates, between 5,000-10,000 seamen were taken from U.S. ships from 1806-1812 with approximately 1,300 of them born in America. Although American politicians rattled their sabers in public, in private they admitted that fully half of the sailors on American merchant ships were actually British subjects who had either abandoned or avoided service in the Royal Navy, which was often cruel and harsh. Nonetheless, many Americans continued to view these actions as an insult to the young nation, a challenge to its honor, and evidence that Great Britain did not accept the independence of the United States.

Many of the War Hawks in Congress were also driven by territorial ambitions and viewed war with Great Britain as on opportunity to seize all or at least part of Canada. Since 1775, when Generals Richard Montgomery and Benedict Arnold led a military expedition across the frozen wilderness of Maine to seize Quebec, American politicians dreamed of acquiring Canada. Speaker of the House Henry Clay, a Kentuckian, argued that Canada was so vulnerable that an attack on the British colony would force Britain to make concessions. At the same time, he claimed that the conquest of Canada would remove a longstanding threat to America’s security on the North American continent and restore national honor. “I believe that in four weeks from the time a declaration of war is heard on our frontier, the whole of Upper Canada and a part of Lower Canada will be in our power,” bragged South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun.

A Not Ready for Prime Time Military

In June of 1812, the United States had neither the army nor the navy to fight and win a war against Great Britain, despite the bravado of American politicians. In the years following independence, the creation and maintenance of a large standing professional army was not a priority for the young republic and there was little interest in investing in one. The prevailing assumption was that state militias would form the basis of any army in times of need, so at the outbreak of the war the regular army consisted of less than 12,000 men. Congress authorized the expansion of the army to 35,000 men as war sentiment increased but service was voluntary and unpopular because it paid poorly. Moreover, because of the heavy reliance on state militias there were few professional and experienced officers. President Thomas Jefferson authorized the establishment of the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1802 but it’s primary purpose early on was to produce a corps of engineers to drive infrastructure improvements.

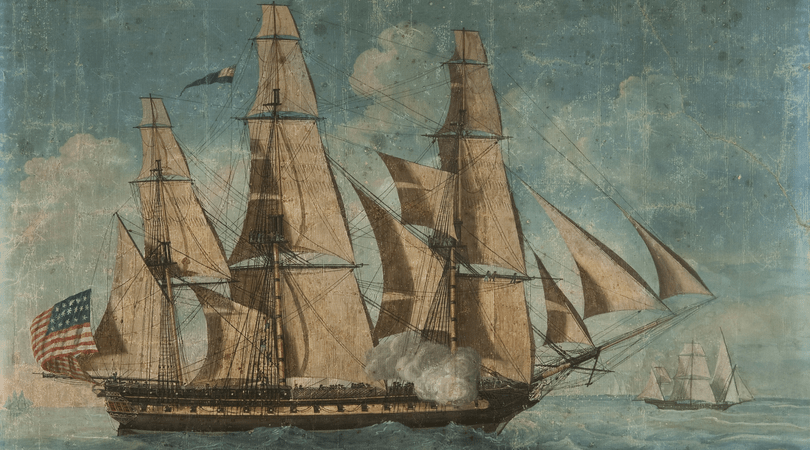

The U.S. Navy was in just as poor shape as the army. Never large to begin with, the navy consisted of less than a dozen ships at the outbreak of the war and included only three frigates. Rather than appropriate funds for a Navy capable of defending U.S. maritime interest, Congress preferred to go the cheaper route and rely on privateers during wartime. In terms of manpower, the U.S. Navy had roughly 5,000 sailors and 1000 marines. The Royal Navy, on the other hand, had 130 ships of the line with 60-120 guns and 600 frigates and smaller vessels as well as 140,000 sailors and 31,000 well trained marines. However, the British had only a fraction of their fleet for use against the United States in the summer of 1812 — one ship of the line, seven frigates, and a dozen smaller vessels — because most of their navy was focused on fighting the French.

War Along the Borderlands

During the first two years of the war, the primary theater of combat was the border lands between the United States and Canada. That fighting would center in this area was hardly surprising. American politicians and military leaders had long coveted Canada and many of the War Hawks in the country were quite transparent about their territorial ambitions. They believed American forces would be welcomed by the Canadians as liberators. Canada was also the closest and easiest place to strike at Britain. On paper, the United States had a clear advantage. The U.S. population totaled roughly 7.5 million compared to about 500,000 Canadians, which included 300,000 of French descent that were not considered reliable. The United States had about 10,000 men under arms at the start of the war with thousands more available for call-up compared to 4,500 British troops spread along the border. Nonetheless, the British were better led, better trained, and better equipped which the Americans would soon realize.

Less than a month after declaring war on Britain, the United States carried out a three pronged invasion of Canada that would ultimately end in failure. The entire operation was marred by gross military incompetence, an over reliance on militia, and poor coordination. On July 12, 1812, a combined force of 2,000 U.S. Army regulars and militia, under the command of General William Hull, a 59 year old veteran of the Revolution crossed into Canada from Detroit. Hull lost his nerve after a series of attacks by Britain’s Indian allies and retreated back to Detroit. Hull later surrendered Detroit to a small British force after being deceived into believing he was surrounded by a larger army. He was later court-martialed and convicted of cowardice and neglect of duty.

In October, General Stephen Van Rensselaer, an inexperienced political appointee, and 3,5000 men, crossed the Niagara River into Canada and attacked a much smaller force of British Redcoats, and their Indian allies at Queenston Heights. The attack was foiled by political infighting amongst the army commanders, a refusal by a large body militia to cross into Canada, and the exploits of a more capable and adept British commander.

In November, General Henry Dearborn, another older veteran from the Revolution, led a 6,000 man force from Albany to the north shore of Lake Champlain. Their goal was to capture Montreal but once again the militia refused to leave the United States. The force retreated without ever entering Canada. The results of the entire Canadian operation were best summed up by a Vermont newspaper, it produced nothing but “disaster, defeat, disgrace, and ruin and death.”

The United States regrouped the following year and with the help of new commanders and more experienced troops attacked Canada again with better results. However, it was still unable to score that decisive victory that would force Britain to the negotiating table. In April, the Americans capture York (now Toronto) and burned several government buildings, an act that later would be avenged when the British burned Washington D.C. in 1814. In September, Admiral Oliver Hazzard Perry destroyed the British fleet on Lake Erie, famously declaring “We have met the enemy and they are ours.” The following month, American troops re-captured Detroit and defeated a combined British-Indian force at the Battle of the Thames, which drove the British from southwestern Ontario. American troops ended the year with the capture of the strategically important Fort George near the mouth of the Niagara River. More fighting took place along the Niagara River in 1814, but the conflict’s center of gravity shifted southward to the Chesapeake by August 1814.

The Chesapeake Shuffle

Following Napoleon’s defeat in April 1814, Britain was now free to focus all its military might on the United States and the target of that focus would be the Chesapeake Bay where American defenses were weak and the British could exploit their greatest advantage, their navy. The previous year, British naval forces under the command of Rear Admiral George Cockburn instituted a naval blockade of the Chesapeake Bay and began raiding coastal towns up and down the Bay in an effort to relieve pressure along the US-Canadian border. Cockburn’s raids made him the scourge of the Chesapeake, and the target of much animus from the U.S. press but they did little to draw large numbers of American troops from the Canadian border.

Cockburn resumed his raids on the coastal Chesapeake towns in early 1814 but he believed the only way to force the Americans to see that the war they were fighting wasn’t worth pursuing was to lead a large force against the US capital itself. In August, an army of 4,500 veteran British troops who’d fought the French for the last 20 years, anchored in the lower Chesapeake under the command of Major General Robert Ross. The arrival of Ross’ army in the Chesapeake unnerved the American leadership prompting heated debate over where the army was likely to strike. Secretary of War John Armstrong strongly believed that the British would most likely try to attack Baltimore because of its commercial importance and did little to strengthen the defense of the capital. In 1814, Washington, DC, had roughly 8,200 residents and many of its major structures, including the Capitol Building, were still works in progress. Nevertheless, it presented an appealing means of retaliation for an American attack against the Canadian Capital of York a year earlier.

On August 19, Ross’ army landed at Benedict, Maryland on the shores of the Patuxent River and began their 35 mile march north toward Washington D.C. In less than a week, they would be at the gates of the capital. A hastily cobbled together force of 6,500 soldiers, sailors, marines, and militia, under the command of General William Winder, engaged the British at Bladensburg, Maryland just five miles from the capital. Although Winder’s men outnumbered their British foes, they were mostly poorly trained militia and no match for the battle-hardened British. Under heavy British pressure, the left flank of the American line of defense crumbled. With their left flank enveloped, the Americans fell back in chaos and a rout that would become known as the “Bladensburg Races” ensued. By 4:00 pm the battle was over and the door to Washington wide open.

Winder’s defeat put the capital in a panic. President Madison, who was at the battle with Winder retreated back to Washington. In his absence his wife supervised the evacuation of the White House. Foregoing their personal items, Mrs. Madison gathered important papers and some national treasures, such as Gilbert Stuart’s revered portrait of George Washington and left the city that evening just before the arrival of the British.

The British Army entered Washington only to find the city largely abandoned. Under orders from General Ross and Admiral Cockburn the British troops proceeded to burn Washington. One British officer described how the British soldiers “proceeded, without a moment’s delay, to burn and destroy every thing in the most distant degree connected with government.” The Capitol was the first building set aflame followed by the White House. Around midnight Ross and Cockburn entered the White House to find that the president’s dinner was still on the table undisturbed. The men proceeded to enjoy their first hearty meal since departing their ships with Cockburn facetiously offering a toast “Peace with America, Down with Madison.” After finishing their meal, the chairs were placed atop of the table and lit on fire. Before the British were done, the Treasury, State Department, and other federal buildings were on fire as well as the Navy Yard. One British officer remarked that if it hadn’t been for Ross, who urged caution, Cockburn would have burned down the whole city. In what can only be viewed as an act of divine providence, Washington was saved from further destruction when a very heavy thunderstorm and tornado passed over the city the following day and put out many of the flames. President Madison returned to the city two days later. Congress briefly considered abandoning Washington to make a capital somewhere else but the city was eventually rebuilt.

On to Baltimore

After the storm had passed, the British army returned to their ships and prepared to contemplate their next move. Following intense debate within the British command over their next course of action, the British fleet sailed north to Baltimore. Baltimore, unlike Washington, had formidable defenses, including Fort McHenry which guarded entry to the city’s inner harbor. Its 13,000 defenders were not just militia but U.S. Army Regulars, Dragoons, sailors, and marines. They were also more ably led by Major General Samuel Smith, a sitting U.S. Senator, who commanded the Maryland militia before the outbreak of the war.

The British plan was to land troops on the eastern side of the city while the navy reduced the fort, allowing for naval support of the ground troops when they attacked the city’s defenders. Encountering no opposition, the British landed a combined force of soldiers, sailors, and Royal Marines at North Point, a peninsula at the fork of the Patapsco River and Chesapeake Bay, on September 12. Determined to conduct an active defense of the city, Major General Smith, sent Brigadier General John Stricker and his 3rd Brigade to Patapsco neck to delay the British advance. Stricker’s brigade numbered about 3,000 and was one of the most capable of all Baltimore’s defenders. Around 1:00 pm Stricker deployed 250 skirmishers and engaged the advanced guard of the British army at North Point. Upon hearing the sounds of battle, the British commander, General Ross, rode forward to evaluate the situation and to order his men to drive the Americans from the field. In the midst of battle, Ross was shot in the chest by an American marksman and fell to the ground mortally wounded.

Command of the British land forces now passed to Colonel Arthur Brooke who gathered the main body of the British army and pressed the attack. Expecting the American forces to flee as they did at Bladensburg, the British were surprised when they held strong and inflicted heavy casualties on their ranks. By the late afternoon the Americans began to give way after repeated assaults by the British and retreated back to Baltimore in good order. The British were forced to pause their advance and regroup allowing U.S. time to prepare better defensive positions. The next day the British would find their advance blocked by 10,000 American troops and 100 cannon. Outnumbered 2 to 1 the British would need naval support to dislodge the defenders and Fort Mc Henry would have to be neutralized.

The Rockets Red Glare…

The British began their bombardment of Fort McHenry early in the morning of September 13. For the next 27 hours British warships hammered the fort with cannon balls, shells, and the relatively new Congreve rockets, seeking to pulverize the fort into submission. Francis Scott Key, a Baltimore lawyer, who was held on board a British warship, negotiating a prisoner release, watched the nighttime attack on the fort from the ship’s deck. At that moment he would compose the famous words, “the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air,” that would go on to become our national anthem in 1931. Over 1,500 pieces of ordnance were fired but it inflicted only minor damage to the fort. The shelling ceased by 7:00 am and an enormous American flag was raised over the fort, signaling victory. Following the failed bombardment of Fort McHenry, Colonel Brooke was forced to abandon the land assault on Baltimore. The British troops returned to their ships, defeated, and set sail, leaving the Chesapeake Bay.

Give Peace a Chance!

Great Britain’s defeat at Baltimore and the United States’ inability to make greater headway in Canada served as great impetus for both sides to sit down at the negotiating table and hammer out a peace agreement. Peace talks between the two sides had started in early August in the Belgian city of Ghent, even before the British attacks on Washington and Baltimore. However, negotiations hit an immediate impasse because of the maximalist positions of each side. British representatives demanded that the United States give control of its Northwest Territory to its Indian allies. They also asked that the United States give part of the state of Maine to Canada, and make other changes in the border. The Americans made equally tough demands. The United States wanted payment for damages suffered during the war. It also wanted the British to stop seizing American sailors for the British navy. And the United States wanted all of Canada. The British representatives refused to even discuss the question of stopping impressment of Americans into the British navy. And the Americans would surrender none of their territory.

Word that the British attacks on Baltimore and Plattsburgh, NY failed, combined with the financial strain that the war was putting on both sides brought a new flexibility to the negotiations. Both Great Britain and the United States struggled to finance the war. The British Prime Minister was aware of growing opposition to wartime taxation and the demands of merchants in Liverpool and Bristol to reopen trade with America. He realized that Britain had little to gain and much to lose from prolonged warfare. On the American side, the country’s finances were in shambles and national debt was ballooning because of the war. In the Spring, Congress had authorized Madison to borrow $32.5 million to pay for the war but by summer the investment climate for U.S. Treasury bonds was dismal, and the government’s inability to borrow money hampered its ability to pay for the defense of Washington. In addition, opposition to the war was growing and the New England states were organizing a convention in Hartford Connecticut to discuss the possibility of secession.

After four months of difficult negotiations the two sides agreed to a peace on December 24, 1814. Remarkably, the treaty said nothing about two of the key issues that started the war–the rights of neutral U.S. vessels and the impressment of U.S. sailors. There were also no territorial concessions. In the end, all the treaty did was establish a return to the antebellum status quo. They simply agreed to end what both sides had come to view as a colossal mistake.

The Republic Lives On!

Even though the War of 1812 ended in a stalemate with no territorial concessions or other prizes, just a return to the antebellum status quo, it doesn’t mean the war was without importance. In the simplest terms, the United States proved it could survive. The war also taught the young republic valuable lessons and opened the door to future territorial expansion.

The United States went toe to toe with arguably the strongest military power of the day and fought it to a draw. In doing so, it demonstrated it could and would fight to preserve its sovereignty and independence. It confirmed the separation of the United States from Great Britain once and for all and forced the British to accept United States as a legitimate national entity.

In the military sphere, it proved that a well funded professional military was necessary and that the young nation could no longer rely on state militias and privateers for its security. Future President John Quincy Adams would write, “The most painful, perhaps the most profitable, lesson of the war was the primary duty of the nation to place itself in a state of permanent preparation for self-defense.”

Lastly, the war opened the door to further territorial expansion. For decades, the British strategy had been to a create a buffer to block American expansion and incited Indian attacks along the United States Western frontier. With the smashing of the Tribal Confederacy, Britain’s Indian allies, a major obstacle to further U.S. expansion West was eliminated.