Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries the Ottoman Turks terrified European Christendom on both the land and on the sea. The Turkish conquest of Constantinople in 1453 marked the collapse of the Byzantine Empire and opened the gates of Europe to the Ottoman scourge. The refusal of Western Christendom to come to the assistance of their Eastern brethren also revealed the vulnerability of a Europe beset by religious conflict. Fast forward more than a 100 years later and Christian Europe—now divided between Catholics and Protestants—once again faced an existential threat from the Ottoman Turks but this time from the high seas. On October 7, 1571, an assembly of Catholic nations and city states, known as the Holy League, defeated the Ottoman navy in epic fashion off the coast of Southwestern Greece in the battle of Lepanto. The battle of Lepanto is the largest naval battle of the Renaissance involving over 500 ships. It is also the last major naval engagement fought primarily between rowing vessels.

The Growing Ottoman Menace

After the fall of Constantinople, the Ottoman Empire steadily increased its holdings across the Mediterranean and Southeastern Europe. By the mid-16th century, the Ottomans had expanded as far North as Budapest. Europeans were too distracted by conflict amongst themselves to rally and blunt the Ottoman advance. The Ottomans also pioneered advances, in shipbuilding, gunnery, and naval tactics, emerging as the dominant naval power in the Mediterranean by this time. The Ottomans controlled lucrative trade routes in he Mediterranean Sea and Turkish galleys roamed the sea with impunity. Raiding parties routinely landed along the coast of Spain, France, and Italy for the purpose of capturing slaves. Males would be forced into bondage as galley slaves while females were sent to harems in the East.

And the Pope Cast his Arms Abroad…

From the Vatican, Pope Pius V watched the growth of Ottoman power and might in the Mediterranean with grave concern. The continued enslavement of his flock certainly troubled the Pope but what was more likely in the forefront of his mind was the inevitable question of when would the Ottomans directly attack Italy and the Vatican itself, especially as the Europeans continued to fight amongst themselves.

For five years, the Pope sought to create an alliance of Roman Catholic states to push back against the Ottoman menace. However, there was little consensus among these states which were preoccupied with other challenges. France and the Hapsburgs were preoccupied with the challenges of the Protestant Reformation. Great Britain was in he process of rejecting Catholicism and forming its own state church. Spain was eager to participate, viewing the Pope’s proposal as a means of asserting its power and influence, but it’s state coffers were practically empty. Venice, the most powerful Catholic maritime power in the Mediterranean, preferred to avoid conflict with Ottomans so as not to jeopardize their lucrative trade routes. It was also concerned about growing Spanish influence on the Italian peninsula. Nonetheless, the Pope refused to give up hope of drawing Venice and the smaller Italian states into an alliance with Spain.

The situation changed dramatically in the Spring of 1571. The previous summer, the Ottomans declared war on Venice and invaded Cyprus, after Venice refused to voluntarily handover the island to the Turks. In May 1571, Pope Pius V, Philip II of Spain and the Venetians agreed to put aside their differences and combine forces in the form of a Holy League. They hastily assembled a vast Christian armada of more than 200 ships, 40,000 sailors and 20,000 troops led by Philip II’s half-brother Don Juan of Austria. In the summer of 1571, the fleet set sail to lift the siege of Cyprus. When Don Juan learned of the fall of the last Venetian stronghold on that island he headed for the Gulf of Patras where the Ottoman fleet was being refit.

As the forces of Christianity and Islam inched closer to an epic battle the outcome was far from certain. Each side possessed distinct advantages and disadvantages. In terms of sheer numbers, the Ottomans outnumbered the Holy League fleet in ships and manpower. The Ottoman fleet consisted of roughly 300 ships. These vessels were manned by 37,000 oarsmen and sailors and carried approximately 34,000 soldiers. In contrast, the Holy League fleet consisted of 206 ships, crewed by 40,000 oarsmen and sailors, carrying only 20,000 soldiers. Nonetheless, the Christian fleet enjoyed a clear advantage in terms of firepower. The Holy League ships had a total of 1,815 cannons. The Turks had only 750 with insufficient ammunition. Moreover, the Holy League troops were armed with muskets and arquebuses while the Ottomans continued to rely on their feared composite bowmen. The Holy League’s advantage in firepower would prove decisive in the forthcoming battle.

The Holy League also believed that they had the Blessed Mother Mary on their side against the heathen Turks. Pope Pius asked Christians throughout Europe to pray the Rosary, seeking the intercession of the Blessed Mother with her Son for a Christian victory. The Pope also ordered churches to conduct continuous periods of Eucharistic adoration and ordered the Rosary Confraternities in Rome to organize processions during which the Rosary was prayed. The faithful of Europe were all fervently praying at the same time for the same purpose: to save Christianity.

A Battle for the Ages

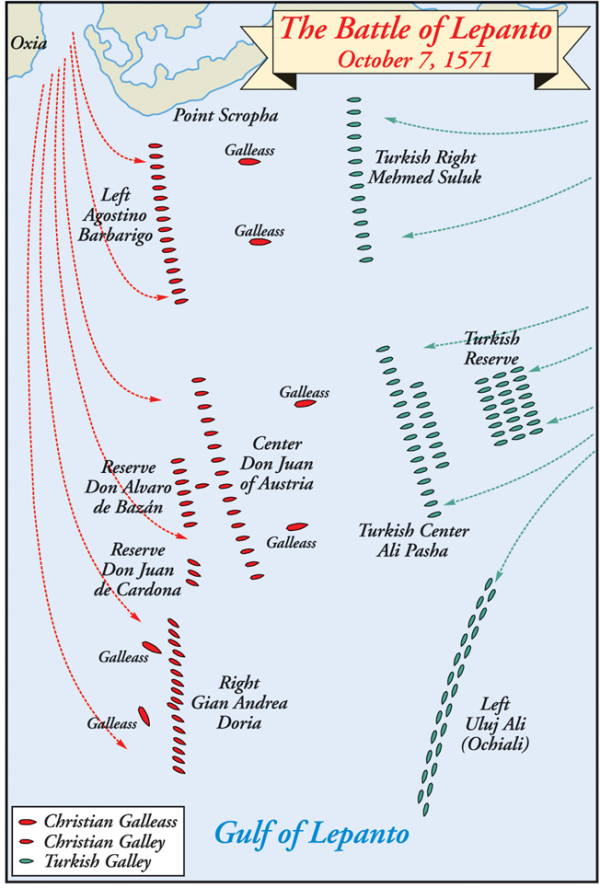

The Holy League fleet entered the Gulf of Patras early on the morning of 7 October and it spotters quickly identified their Ottoman adversaries far off in the distance. Both sides were determined to give battle that day and began the necessary preparations as they moved to close the distance between them. The Ottomans, under Ali Pasha, had their ships arrayed in the form of a crescent and proceeded to advance West with the wind at their backs. The Holy League found itself in the less enviable position of heading East into the wind and it was uncertain whether the fleet would be able to form a battle line before the Ottomans engaged. Miraculously and unexpectedly, the wind completely reversed directions as if there was a divine intervention, and it was now the Holy League with the advantage.

Don Juan, divided his command into four squadrons. On the left, he placed the soft-spoken but fierce-fighting Venetian Agostino Barbarigo. Juan led the central squadron, supported by the Venetian Admiral Sebastiano Veniero and the papal commander, Marc Antonio Colonna. On the right, Genoese Admiral Gian Andrea Doria was placed in command. Juan also prudently created a reserve squadron, under the command of the Spaniard, Marquis de Santa Cruz, the Holy League’s most respected admiral. At the head of each of his front squadrons, he placed two Venetian galleasses—larger, heavily armed ships, with higher sides that were difficult to board— to break up the Turkish attack.

By nine o’clock the two lines were fifteen miles apart and closing fast. The men of each side steeled themselves for the forthcoming battle. Priests bearing large crucifixes administered the Sacrament and heard final confessions. The Holy League’s battle standard, a gift from the Pope was unfurled and men up and down the battle line cheered as they saw the giant blue banner bearing an image of the crucified Jesus Christ. In the Ottoman fleet gongs and drums blared while the sacred banner with Allah’s name stitched in gold calligraphy was raised.

Around 10 am, the battle commenced. The Holy League drew first blood as four Venetian galleasses opened fire, sinking several Turkish galleys. As the two fleets drew closer, more cannons erupted, arrows rained on the Christians, and Spanish arquebuses spat back balls of lead at the Turks. The first direct engagement between the two fleets occurred on the Christian left, where the faster Turkish galleys tried to outflank the Catholic fleet, but were driven back against Scropha Point. Amidst the melee, ships rammed one another with the decks of the tangled galleys serving as a floating battleground for hand to hand combat. Here the soldiers of the Holy League, mostly armed with arquebuses and muskets, were able to decimate the Turkish archers. During the course of the battle, the commander of the Holy League squadron Admiral Agostino Barbarigo fell with an arrow through the eye. His Ottoman counterpart, Mahomet Sirocco, was killed in action and beheaded by one of Barbarigo’s Venetian soldiers. Ill-prepared and out-gunned, the Ottoman galleys began to sink below the waters or were taken by the Holy League as prizes. By early afternoon, the Catholic left had emerged victorious.

In the center the fighting was even more fierce and desperate. Both the Ottomans and the Holy League placed the preponderance of their ships in the center of their line. It is also where the two fleet commanders Don Juan and Ali Pasha deployed their flagships. Usually, the flagships would stand off from the heat of battle, but not this time; both supreme commanders set a hard course for each other. Ali Pasha’s Sultana gained the initial advantage by ramming into the Real. Don Juan grappled the two ships together and boarded. Instantly, a dozen Turkish ships closed in behind Ali Pasha, supplying him with thousands of janissaries. The janissaries had almost taken the Real before the Papal flagship, the Capitana, under Marcantonio Colonna, appeared alongside and mounted a counterattack. The surging Catholic forces drove back the Ottoman janissaries in what had become an infantry battle fought across ships’ decks. The entire crew of the Sultana was killed, including Ali Pasha himself, who was beheaded and had his head foisted on a pike for all to see. The banner of the Holy League was raised on the captured ship, breaking the morale of the Turkish galleys nearby. After two hours of fighting, the Turks were beaten left and center although fighting continued for another two hours.

Ottoman forces attacking on the Holy Leagues right had one last chance to steal a victory out of defeat. The Turkish commander Uluch Ali feigned a flanking maneuver leading the Holy League ships to shift their positions creating a gap between the Catholic right and center. Many Ottoman galleys penetrated the gap, inflicting heavy casualties on the Maltese contingent that bore the brunt of the attack. However, disaster was averted by the timely intervention of the Holy League reserve squadron that drove back the Turks and closed the gap.

By 4 PM, the battle was over. The Ottomans lost 187 ships sunk or captured. Human losses reached around 20,000 killed, wounded, and captured. During the course of battle, about 12,000 Christian slaves were liberated from the Turkish galleys. Holy League loses were more modest, including 13 ships and 7500 killed, wounded and captured.

Aftermath

Lepanto was a decisive victory for the Holy League, one that stopped Ottomans’ expansion into the Mediterranean confirming the de facto division of the Mediterranean into an eastern half under Ottoman control and a western half under the Hapsburgs and their Italian allies. It also showed that the previously unstoppable Turks could be beaten.

The Holy League collapsed in 1573, consumed by political infighting and the Ottomans quickly rebuilt their fleet within six months. By 1572, about six months after the defeat, more than 150 galleys, 8 galleasses, and in total 250 ships had been built, including eight of the largest capital ships ever seen in the Mediterranean. With this new fleet the Ottoman Empire was able to reassert its supremacy in the Eastern Mediterranean but it no longer posed the same threat to the Western Mediterranean it once did.

Word of the great naval victory at Lepanto reached the Vatican on October 22. People were jubilant, Church bells rang and joyful praise was given to the Blessed Mother for her intercession. Soon the pope added a feast day, Our Lady of Victory, as an obligatory memorial to the Church calendar, celebrated every October 7. The victory at Lepanto and the intercession of the Blessed Mother garnered from the faithful praying the rosary, would thus be perpetuated in Catholic memory. The name of the feast changed over the centuries and became known by the current title, Our Lady of the Holy Rosary.