Early on the morning of April 12, 1861, South Carolina militia forces opened fire on the Federal garrison, Fort Sumter, in the middle of Charleston harbor. After a sustained heavy bombardment of the fort, garrison commander, United States Army Major Robert Anderson, reluctantly surrendered the following afternoon. This brazen attack would prove to be the opening spark of the American Civil War, a four year conflict that would claim the lives of over 600,000 Americans and leave an indelible mark on the historical development of the nation.

A Nation on the Brink

The United States in the decade before the Civil War was a country fraying apart at the seams. It was an increasingly polarized nation bitterly divided over the issue of slavery, which permeated all political discourse and debate. The Founding Fathers largely sidestepped the issue of slavery at the Constitutional Convention in order to create a document acceptable to all. However, in doing so they left a number of questions unanswered, most importantly the extension of slavery. In a number of compromises designed to placate slaveholders, the Constitution implicitly endorsed the institution of slavery where it already existed, but it said nothing about whether slavery would or would not be allowed in any new territories or states that might enter the union subsequently. As the nation steadily expanded its frontiers in the first half of the 19th century, that question alone tore the nation asunder, especially because with the admission of each slave or non-slave state the existing balance of power between pro-slavery and anti-slavery forces shifted. As such, American politics became a constant struggle between pro-slavery and anti-Slavery forces for political power and what side would gain the upper hand. The tension inside the country was summed up succinctly by the New York Tribune publisher, Horace Greeley, in 1854, “”We are not one people. We are two peoples. We are a people for Freedom and a people for Slavery. Between the two, conflict is inevitable.”

The 1850s were a particularly tumultuous decade that only served to sharpen the dividing lines between those who supported slavery and its unlimited expansion and those who did not. For the opponents of slavery, the decade was a series of setbacks that only served to increase their anger. In 1850, Congress adopted a controversial Fugitive Slave Law as part of a larger compromise to admit California to the union as a free state. This new law drew the scorn of many northerners because it forcibly compelled all citizens to assist in the capture and return of runaway slaves. In 1854, the Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed allowing people in the territories of Kansas and Nebraska to decide for themselves whether or not to allow slavery within their borders, effectively invalidating the 1820 Missouri Compromise, which precluded the admission of any new slave states north of Missouri’s southern border. The act would touch off a bloody guerilla war in Kansas between pro and anti-slavery forces while infuriating many northerners who considered the Missouri Compromise to be a binding agreement. Three years later the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in its infamous Dred Scott decision, that the Federal Government had no authority to restrict the institution of slavery. All of these developments only served to convince the more radical anti-Slavery elements that the Federal Government was under the thrall of “slave power,” a cabal of wealthy Southern slaveholders who wielded disproportionate influence in Washington and that more deliberate and decisive action would be needed to end slavery.

For all the angst that permeated the abolitionists and the anti-slavery forces about the disproportionate influence that the South wielded over the Federal government, pro-slavery elements were equally uneasy about their standing. The slave holding states continued to view Northern abolitionists as a persistent threat to their prosperity and way of life. They clearly understood that if slavery did not continue to expand they would soon find their political power and their ability to defend their interests eroded with the admission of each new free state to the union. Southerners enthusiastically supported the annexation of Texas in 1845 and most favored war with Mexico a year later as a means to acquire more territory to create additional slave states, despite opposition from anti-slavery forces in the north. At the same time, increasingly aggressive agitation by Northern abolitionists stoked ever present fears in the South of violent slave insurrections. For many Southerners, John Brown’s attempt to incite a slave revolt with his raid on the Federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry in October of 1859 was only confirmation of their worst fears.

The Election of 1860

If John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry was confirmation for the South of Northern abolitionists’ malign intent, the 1860 election of Abraham Lincoln was the last straw for many Southerners, who now saw no other alternative than to secede from the Union. The 1860 election was divisive from the start, featuring four major candidates. Abraham Lincoln was the nominee of the newly minted Republican Party. The Democratic Party split along regional lines. The northern wing of the party nominated Lincoln’s long standing rival, Senator Stephen Douglass of Illinois. The southern wing of the party named the pro-slavery former Vice President, John J. Breckinridge of Kentucky as its candidate. Lastly, the hastily formed Constitutional Unionist party, former conservative Whigs who argued for compromise on the slavery issue and opposed secession, selected John Bell, a Tennessean, as its standard bearer. Lincoln prevailed overwhelmingly, winning both the electoral college and the popular vote by considerable margins. However, he did not win a single electoral vote from any state below the Mason-Dixon Line.

“The issue before the country is the extinction of slavery…The Southern States are now in the crisis of their fate; and, if we read aright the signs of the times, nothing is needed for our deliverance, but that the ball of revolution be set in motion.”

– Charleston Mercury on November 3, 1860

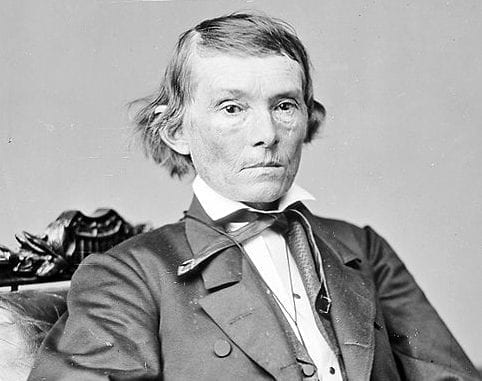

Rabid secessionists or “Fire Eaters” in the South, as they were called, who had long argued that the South should secede from the Union, now found their casus beli with the election of Lincoln. Lincoln was no abolitionist. Even though he personally opposed slavery, especially its extension into the territories, Lincoln was prepared to sustain the institution where it was already established in order to preserve the Union. Nonetheless southern Fire Eaters argued Lincoln was or would come under the thrall of Northern abolitionists and called urgently for secession. On December 20, 1860 by a vote of 169-0, the South Carolina state legislature enacted an “ordinance” that stated “the union now subsisting between South Carolina and other States, under the name of ‘The United States of America,’ is hereby dissolved.” South Carolina was soon followed by Mississippi which seceded on January 9, 1861, Florida (January 10), Alabama (January 11), Georgia (January 19), Louisiana (January 26) and Texas (February 1). Representatives from these seven states gathered in Montgomery Alabama and proclaimed a new Confederate States of America with Jefferson Davis of Mississippi as President and Alexander Stephens of Georgia as Vice President.

The Crisis Unfolds

Following their secession, the seven former states of the Confederacy almost immediately set about asserting their sovereignty and independence. In practical terms, that meant seizing all federal property on their territory, most importantly forts, shipyards and other military installations. In South Carolina, the birthplace of secession, all attention was focused on several forts and batteries protecting Charleston Harbor. Most important among these was Fort Sumter which controlled all access to and from Charleston Harbor.

Almost immediately after South Carolina’s secession Governor Francis W. Pickens demanded that all federal forces evacuate these facilities and turn them over to the South Carolina militia. Unwilling to give in to rebel demands but cognizant of their vulnerability and isolation, Federal military forces began to consolidate at Fort Sumter. For the secessionist, this brazen act of defiance was an outrage and indication that the situation would not be resolved easily.

President James Buchanan was reluctant to provoke a crisis with South Carolina out of concern the other slave states might secede but he also understood the small garrison at Fort Sumter was now effectively under siege and could not be expected to hold out long without reinforcements or resupply. On January 5, 1861, Buchanan sent a merchant ship from New York, the Star of the West, with some 200 reinforcements and provisions for the fort. As the ship approached Charleston Harbor on January 9, cadets from the Citadel opened fire on the ship with artillery, forcing the crew to abandon its mission. No further resupply efforts were made in the waning days of the Buchanan administration.

On March 1, the Confederate States government assumed control of the military operations in and around Charleston Harbor. President Jefferson Davis, sent Brigadier General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard to take command and supervise the siege. Beauregard was a well-trained military engineer and strategically placed artillery at various points around Charleston Harbor, effectively ringing the fort. He also took steps to ensure that no supplies from the city were available to the defenders, whose food was running low.

With conditions in Fort Sumter deteriorating rapidly, the newly inaugurated Lincoln Administration now faced its first crisis. Determined to show strength and resolve in the face of rebel belligerence, President Lincoln notified Governor Pickens on April 6 that he was sending On April 6, Lincoln notified Governor Pickens that he was sending two ships to resupply the fort with provisions and as long as these operations were not interfered with no further efforts strengthen the fort with additional men, weapons and ammunition would be made without further notice. Lincoln’s gambit only provoked another ultimatum from the Confederates, demanding that Federal troops immediately evacuate Fort Sumter or risk annihilation.

Davis ordered Beauregard to continue to press for the fort’s surrender and if it did not, to shell the fort into submission before the relief expedition arrived. Early on the morning of April 11, Beauregard again urged the fort to surrender but its commander Major Robert Anderson refused commenting, “I shall await the first shot, and if you do not batter us to pieces, we shall be starved out in a few days.” The next day Beauregard sent a follow up message to Anderson seeking further clarification and to see if there was a way to avoid any unnecessary bloodshed. In the message Beauregard wrote, “If you will state the time which you will evacuate Fort Sumter, and agree in the meantime that you will not use your guns against us unless ours shall be employed against Fort Sumter, we will abstain from opening fire upon you.” Anderson replied that he would evacuate Sumter by noon, April 15, unless he received new orders from his government or additional supplies. Judging Anderson’s reply unacceptable the Confederates prepared to bombard the fort.

The Attack Begins

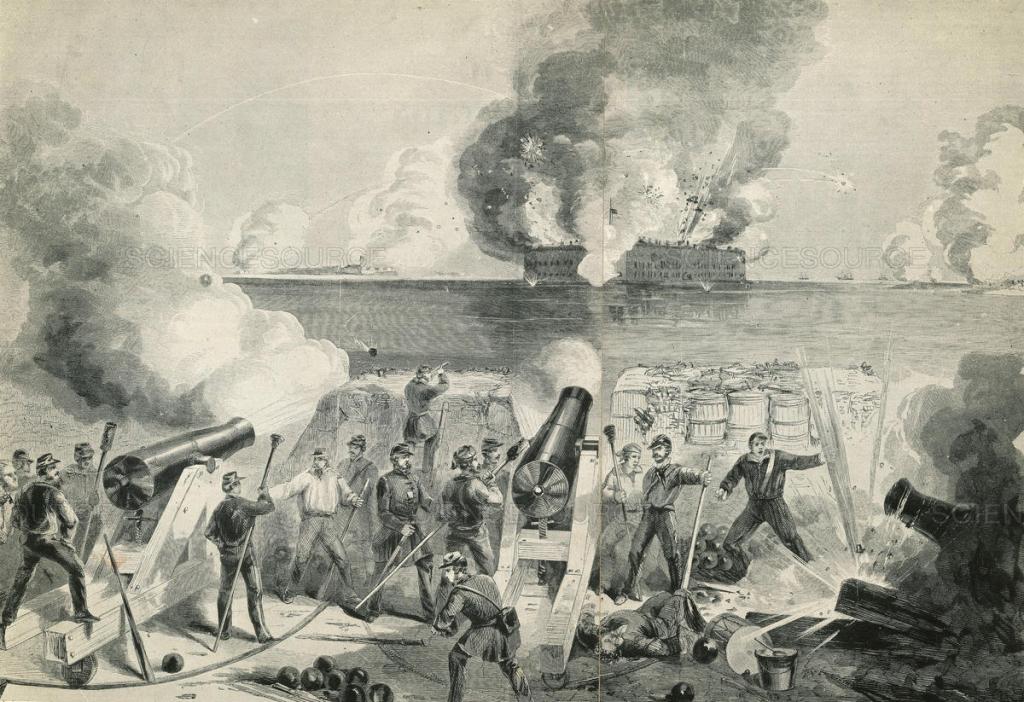

At 4:30 am, on April 12, 1861, a single mortar shell from Confederate artillery deployed at Fort Johnson exploded over Fort Sumter signaling the beginning of the attack. Within minutes 43 Confederate artillery pieces of varying accuracy and power began to methodically shell the beleaguered fort going in a clockwise direction around the harbor, two minutes between each shot. Two hours had passed and the Confederates fired over 200 shots before the fort’s defenders returned fire. Anderson was well aware of the garrison’s shortages of powder and shot and didn’t want waste any firing aimlessly in the dark.

As the battle raged, all of Charleston turned out to watch. Business was suspended and people surged out into the streets and down to the Battery in the south end of the city to get a better view. Wealthy residents climbed to the roofs of their stately manors with picnic baskets and every steeple and every cupola in the city were crowded with spectators. It was a festive atmosphere as excitement drowned out any sense of worry or fear about what would come next.

Confederate solid shot continued to pound away at the stone walls of the fort while exploding shells and heated shot set fire to the wooden structures inside the fort. Because of limited man power, Fort Sumter’s defenders could only fire 21 of its 60 cannon at a time. Moreover, shortages of cartridge bags, projectiles and other necessary equipment forced Anderson and his men to be more conservative in their return fire. Because of these shortages, Anderson reduced his firing down to only six guns.

Night fell and by 7pm the Confederates had scaled back their fire to four shots per hour. Anderson and his men stopped their fire for the evening to conserve their rapidly diminishing resources and a timely rain shower managed to extinguish some of the fires that were raging inside the fort. Outmanned, outgunned, undersupplied, and nearly surrounded by enemy batteries, the garrison was was holding on but just barely. They would live to see another day.

The following morning, the Confederate bombardment resumed with the same intensity as the day before. The Confederates were firing hot shot almost exclusively with devastating effect and by noon most of the wooden buildings in the fort and the main gate were on fire. Around 1:00 the fort’s flagpole was shot down and the flag re-raised from the ramparts on a make-shift staff. With prospects for surviving another day diminishing, Anderson ordered his men to double their rate of fire. He would go down fighting. By 2:30, it was clear that Federal troops could hold on no longer and Anderson surrendered.

Aftermath

Remarkably, neither side suffered any casualties during the bombardment but the consequences of the attack were enormous. In South Carolina and the rest of the states in rebellion, Anderson’s surrender was celebrated as a great victory and provided a patriotic jolt for the new Confederacy with only little concern for what would come next. In Washington, the brazen attack would prompt Lincoln to issue the call for 75,000 volunteers for 90 day enlistments to suppress the rebellion. Lincoln’s plea would lead Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas and Tennessee to join their Southern brethren in the new confederacy but the remaining states where slavery was permitted would stay true to the Union, Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware. Nonetheless, even though these states would remain in the Union many were anti-war there were strong southern sympathies in some of these states. A week after Lincoln’s call for volunteers, rioters in Baltimore attacked the train cars carrying Massachusetts militia heading to Washington to help protect the capital. The Civil War had begun.