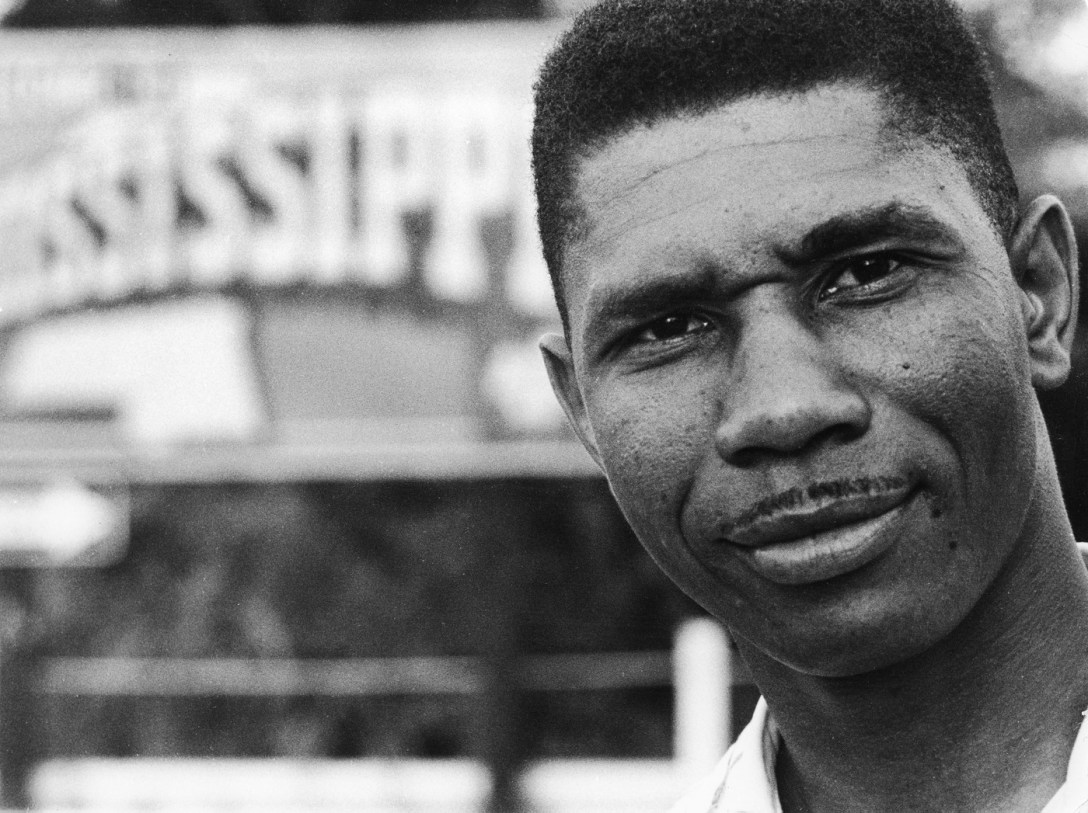

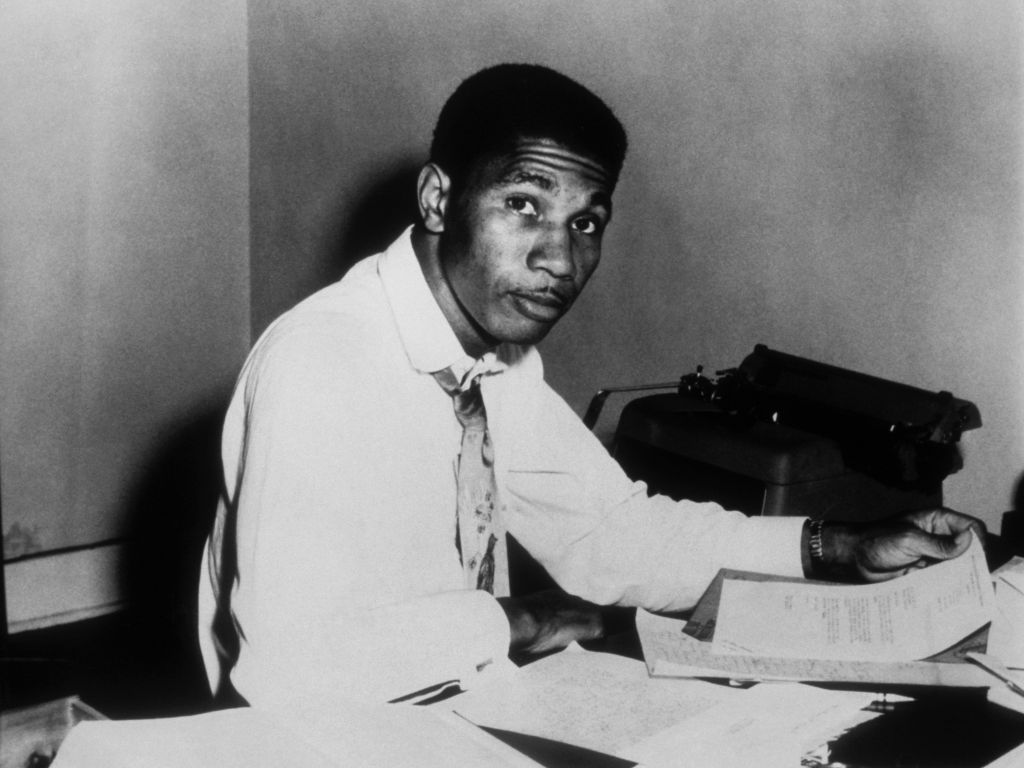

On June 12, 1963, civil rights activist Medgar Evers was gunned down in his driveway outside his home in Jackson Mississippi by white supremacist and segregationist Byron De La Beckwith. Emerging from his automobile after a late night NAACP meeting, Evers was shot in the back by Beckwith who had been positioned across the street waiting to ambush him. The bullet pierced through his heart but he managed to stagger to his door. Evers’ wife, Myrlie, and his three children—who were still awake after watching an important civil rights speech by President John F. Kennedy—heard the gun shot and hurried outside. They were soon joined by neighbors and police. Evers was rushed to the hospital where he was initially denied admission because of his race. He died less than 50 minutes later at the age of 37. Evers was buried on June 19 in Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors.

Evers was a decorated World War II veteran who had fought at Normandy in 1944. However, like many other African-American veterans, he returned to a nation that denied him his citizenship rights at the polls. In 1946, Evers attempted to cast a ballot but twenty armed white men, some of whom had been his childhood friends, had learned of his plans to vote and turned up to threaten him. Evers feared for his life. “I made up my mind that it would not be like that again,” he vowed.

Shortly after the landmark Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, Evers volunteered to challenge segregation in higher education and applied to the University of Mississippi School of Law. He was rejected on a technicality, but his willingness to risk harassment and threats for racial justice caught the eye of national NAACP leadership; he was soon hired as the organization’s first field secretary in Mississippi.

Evers was one of Mississippi’s leading civil rights activists. He fought racial injustices in many forms from segregation to how the state and local legal systems handled crimes against African Americans. Evers’ work put him squarely in the crosshairs of the White Citizens Council, a white supremacist group formed in the aftermath of the Brown ruling devoted to preserving segregation. He garnered national attention for organizing demonstrations and boycotts to help integrate Jackson’s privately owned buses, the public parks, Mississippi’s Gulf Coast beaches as well as the Mississippi State Fair. He led voter registration drives, and helped secure legal assistance for James Meredith, a black man whose 1962 attempt to enroll in the University of Mississippi was met with riots and state resistance.

Beckwith was arrested on June 21, 1963 for the murder of Evers but would escape conviction for most of his life, largely due to the racist system of justice that dominated the deep South in the 1960s. He was tried twice in February and April 1964 but in each trial the two all white juries failed to reach a verdict resulting in two mistrials. Beckwith received the support of some of Mississippi’s most prominent citizens, including then-Governor Ross Barnett, who appeared at Beckwith’s first trial to shake hands with the defendant in full view of the jury. After his release Beckwith bragged about his skill with a rifle and hinting to segregationist friends that, indeed, he had killed Evers.

That Beckwith would not be held accountable, while reprehensible, was hardly surprising and consistent with what was increasingly the norm across the South. African-Americans and civil rights activists could expect little legal protection from the courts and law enforcement in the 1960s South which operated largely to preserve segregation and often ignored the facts when white defendants were accused of harming African-Americans. Moreover, most African-Americans were still disenfranchised by Jim Crow laws and therefore ineligible for jury duty. The two white men who murdered fourteen year old Emmet Till eight years earlier for allegedly whistling at a white woman were acquitted . The Ku Klux Klan members that perpetrated the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama later that year also escaped justice. The same for the murderers of three civil rights workers in Mississippi the following year.

Evers was one of Mississippi’s leading civil rights activists. He fought racial injustices in many forms from segregation to how the state and local legal systems handled crimes against African Americans. Evers’ work put him squarely in the crosshairs of the White Citizens Council, a white supremacist group formed in the aftermath of the Brown ruling devoted to preserving segregation. He garnered national attention for organizing demonstrations and boycotts to help integrate Jackson’s privately owned buses, the public parks, Mississippi’s Gulf Coast beaches as well as the Mississippi State Fair. He led voter registration drives, and helped secure legal assistance for James Meredith, a black man whose 1962 attempt to enroll in the University of Mississippi was met with riots and state resistance.

Evers’ assassination was a pivotal moment in the Civil Rights movement, a bloody milestone in the fight for racial equality that began with the murder of 14 year-old Emmett Till eight years earlier. It would also prove to be a harbinger of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. by James Earl Ray five years later.