In the early morning hours of June 25, 1950, the army of the People’s Democratic Republic of Korea stormed across the 38th parallel into the Republic of South Korea in an attempt to unify the Korean Peninsula under Communist rule. The war would see-saw back and forth over the next three years with no clear victor. The fighting would end in June 1953 with the belligerents agreeing to an armistice at Panmunjom. However, no peace treaty was ever signed and both sides technically remain at war. The Korean War would demonstrate that the United States would not shrink in the face of Communist aggression. It would also exert powerful influence over the U.S. defense establishment, introducing a new concept known as “limited war,” give birth to the Eisenhower administration’s New Look defense policy, and shape U.S. attitudes toward intervention in and the conduct of what would later become the Vietnam War.

One Peninsula Two Koreas

After Japan’s surrender in World War II, the Korean peninsula was divided at the 38th parallel split two zones of occupation – the U.S.-controlled South And the Soviet-controlled North. There was an understanding between the United States and the Soviet Union that the division was a temporary condition until the Koreans were deemed ready for self-rule. Beyond this rather vague agreement, however, much about the future of Korea was left uncertain.

By 1948, the Cold War was in full swing and the dividing lines in both Europe and Asia, once thought to be temporary, became permanent. The Soviets established a socialist state in the north under the totalitarian leadership of Kim il-Sung and a capitalist state in the south emerged under the authoritarian strongman Syngman Rhee who was installed as the South Korean leader by the Office of Strategic Services, the predecessor to the Central Intelligence Agency. Both governments of the two new Korean states claimed to be the sole legitimate government of all of Korea, and neither accepted the border as permanent.

It was clear early on that Kim il-Sung had ambitions to reunite the two Koreas through military force. The North Koreans had been sponsoring a communist insurgency inside South Korea and provoking border clashes with South Korean military forces since 1948 but the naturally cautious leader of the Soviet Union, Josef Stalin, whose assistance and approval would be necessary for any invasion of the South was reluctant to give the go ahead. Stalin worried how the US would respond to any invasion of South Korea but three factors would influence his decision making calculus. In 1949, the Soviet Union would successfully test its own atomic weapon and and in October the Chinese Communist under Mao Zedong finally defeated Chiang-Kai-Shek and his nationalists to gain power in China. Lastly, in January 1950, Secretary of State Dean Acheson delivered a highly publicized speech at the National Press Club in which he laid out the United States’ vital interests in Asia and those it was willing to go to war for. In his speech Acheson mistakenly omitted South Korea.

In April 1950, Stalin reportedly gave Kim permission to attack the government in the South under the condition that Mao would agree to send reinforcements if needed. Stalin made it clear that Soviet forces would not openly engage in combat, to avoid a direct war with the US. Kim met with Mao in May 1950 . Mao was concerned the US would intervene but agreed to support the North Korean invasion. China desperately needed the economic and military aid promised by the Soviets.However, Mao sent more ethnic Korean PLA veterans to Korea and promised to move an army closer to the Korean border.Once Mao’s commitment was secured, preparations for war accelerated.

The Cold War Turns Hot

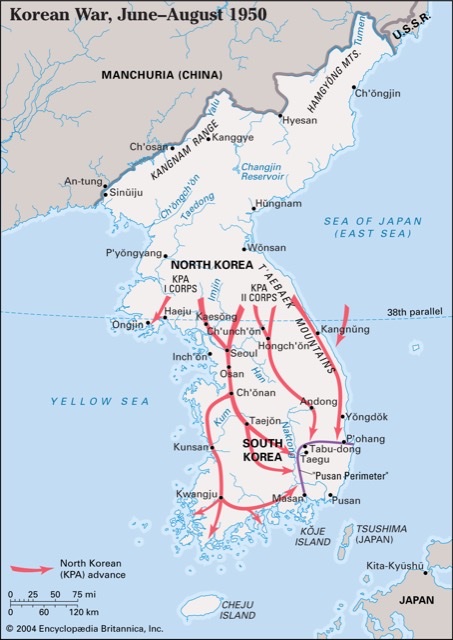

The North Korean Peoples’ Army (NKPA) invaded South Korea at Dawn on the morning of Sunday, June 25, 1950, under the fabricated pretext that South Korean military forces attacked first. Catching South Korean and U.S. military forces completely by surprise, the North Korean penetrated deep into South Korea. U.S. military planners had been fixated on the potential for a major military conflict with the Soviet Union in Europe and did not anticipate that the first test of U.S. resolve and the first military conflict between the United States, the Soviet Union, and their proxies in the new Cold War would be a localized war in Asia on the remote Korean Peninsula.

The United States reacted swiftly to the news of the invasion by immediately taking steps to convene the United Nations Security Council. For, the United States this was not simply a intra-Korean conflict but war against international communism. On June 27th the Security Council asked UN members to provide military assistance to help South Korea repel the invasion. The United States appeal to the UN was successful only because the Soviets were boycotting the UN in protest because of its refusal to recognize the new Communist Peoples’ Republic of China as the legitimate government of the Chinese people. U.S. forces entered the conflict on June 30th but by this time the North Koreans had taken the South Korean capital of Seoul and continued to drive South. Because of the extensive defense cuts after World War II and the emphasis placed on building a nuclear bomber force, none of the U.S. Armed Forces were in a position to make a robust response with conventional military strength. By August, the North Koreans had pushed the South Korean military forces and the U.S. Eighth Army back to the port of Pusan in what would become desperately known as the “Pusan Perimeter.” The North Koreans continued to press the attack on the Pusan perimeter as the US continued to ferry troops in from Japan in an attempt to buy time.

To relieve the pressure on the Pusan perimeter, General Douglass MacArthur, the overall commander of U.N. and South Korean military forces, planned a bold and audacious amphibious landing behind enemy lines at Inchon. On September 15, 1950, over 50,000 American troops from the 1st Marine Division and the 7th Infantry Division landed at Inchon taking the North Koreans completely by surprise and within two weeks liberated the capital of Seoul. With their supply lines now threatened by the loss of Seoul the North Korean army began to fall back from Pusan and across the 38th Parallel.

The retreat of the NKPA back across the border presented the United States and its U.N. allies with a conundrum, whether or not to pursue them across the 38th Parallel. Up until this point of the conflict, the US and its allies had been on the defensive. The U.N. mandate for intervention only pertained to resisting North Korean aggression. It authorized no offensive operations to reunite the peninsula under democratic rule. Lastly, Chinese leaders began to issue not so subtle warnings to the US that China would intervene militarily in the conflict if the US crossed the 38th Parallel into North Korea. On 27 September, the Joint Chiefs of Staff sent to General MacArthur a comprehensive directive to govern his future actions: the directive stated that the primary goal was the destruction of the North Korean army, with unification of the Korean Peninsula under Rhee as a secondary objective. Three days later, Secretary of Defense, General George C. Marshall authorized MacArthur to cross the border into North Korea but to be watchful for any signs of Chinese intervention.

The Chinese Counterattack

MacArthur’s decision to pursue the retreating North Korean army back across the 38th Parallel prompted a great deal of angst in Moscow and Beijing. Chinese Prime Minister Zhou Enlai publicly warned:”The Chinese people will no supinely tolerate seeing their neighbors savaged by the imperialists.” In a back channel warning to the United States, Zhou told the Indian ambassador, that if the American troops entered North Korea, China would intervene in the war. On 1 October 1, 1950, the day that UN troops entered North Korea the Soviet ambassador to China forwarded a telegram from Stalin to Mao Zedong requesting that China send five to six divisions into Korea, and Kim Il-sung sent frantic appeals to Mao for Chinese military intervention. At the same time, Stalin made it clear that Soviet forces themselves would not directly intervene.

Chinese military intervention to save the North Koreans was not a certainty, despite the repeated warnings that Beijing was sending. MacArthur’s rapid advance posed a clear and present danger for China which could not be sure that the UN forces wouldn’t cross over the Yalu River and try to topple the new Peoples’ Republic or at a minimum install a hostile regime along its border. Mao clearly supported the idea of intervening but other members of the Chinese Leadership were more wary. In a series of emergency meeting from October 2-5, Chinese leaders debated the merits of a military intervention in the Korean conflict before reaching a consensus in favor of such action. To enlist Stalin’s support, a Chinese delegation led by Zhou Enlai arrived in Moscow on October 10. Stalin initially agreed to send military equipment and ammunition but warned Zhou that the Soviet Air Force would need two or three months to prepare any operations. In a subsequent meeting, Stalin told Zhou that he would only provide China with equipment on a credit basis and that the Soviet Air Force would only operate over Chinese airspace, and only after an undisclosed period of time. Stalin did not agree to send either military equipment or air support until March 1951.

Pushing further North, the UN forces captured the North Korean capital of Pyongyang on October 19. That same day, Beijing ordered more than 250,000 “volunteers” under General Peng Dehuai to secretly cross over the Yalu into North Korea. The Peoples’ Volunteer Army (PVA) as it became known, launched its first combat operation on October 25, routing the South Korean II Corps at the Battle of Onjong. A week later, the PVA surprised U.S. military forces, encircling the entire 8th Cavalry Regiment at the Battle of Unsan in one of the most devastating U.S. loses in the entire war. The surprise Chinese assault sent the US forces reeling back to the Ch’ongch’ on River unsure whether they were attacked by Chinese or North Korean military forces. In retrospect the events on the battlefield in late October and early November 1950 were harbingers of disaster ahead. They had been foreshadowed by ominous “signals” from China, signals relayed to the United States through Indian diplomatic channels. The Chinese, it was reported, would not tolerate a U.S. presence so close to their borders and would send troops to Korea if any UN forces other than ROK elements crossed the 38th Parallel.

By the second week of November, MacArthur and the rest of UN command finally acknowledged that Chinese military forces had indeed entered the conflict but continued to downplay the significance of the intervention and vastly underestimate the number of forces involved. The PVA had pulled back to regroup after the battles of Onjong and Unsan because of ammunition and food shortages which reinforced MacArthur’s preconceived ideas that any Chinese involvement in the conflict was minimum. MacArthur argued that there were no more than 25,000 Chinese troops inside North Korea, when in fact the PVA now numbered closer to 300,000. Overconfident from his previous success and undaunted by this new foe, MacArthur planned a new “end the war” offensive, a drive to the Yalu, which he promised would end the war by Christmas. The Chinese had other plans.

The UN forces launched their “Christmas Offensive” on November 24 and for the first twenty-four hours they encountered little enemy opposition. However, the Chinese were waiting in ambush and the following evening they carried out a series of surprise attacks against the U.S. Eighth Army along the Ch’ongch’on River Valley almost encircling the entire army. It was soon apparent that the bulk of the enemy forces were not NKPA but organized Chinese Communist units and that there were many more than the 70,000 U.S. military intelligence assessed. On November 27, the Chinese attacked the U.S. X Corps near the Chosin Reservoir, encircling the 1st Marine Division. These forces would eventually breakout after nine days of heavy fighting, and carry out a successful withdrawal to the coast. Pressing their advantage, the Chinese pushed the UN forces 300 miles back down the peninsula and across the 38th parallel with the South Korean capital changing hands a third time on January 4, 1951. The operation which began with such confidence and optimism, was a complete disaster and perhaps the greatest debacle the U.S. armed forces suffered in the entire twentieth century.

As UN forces retreated back down the peninsula and across the 38th parallel, MacArthur warned that the United States now faced “an entirely new war.” He refused to accept any responsibility for the flawed offensive or that he had disobeyed a specific order from the Joint Chiefs to use no non-Korean forces close to the Manchurian border. He denied that his strategy had precipitated the Chinese invasion and argued his inability to defeat the new enemy was due to restrictions imposed by Washington that were “without precedent,” instead of acknowledging his own failure to take the Chinese threat seriously. In December 1950, MacArthur requested permission to use nuclear weapons against the Chinese. He also called for instituting a naval blockade of China, authorization to bomb Chinese military installations in Manchuria and bridges across the Yalu, the deployment of Chiang Kai-shek’s Chinese Nationalist forces in Korea, and launching of an attack on mainland China from Taiwan. Truman flatly refused these requests and a very public argument began to develop between the two men.

The President vs. the General

The complete and abject failure of MacArthur’s offensive and China’s intervention into the war forced a great deal of soul searching amongst U.S. political and military leaders as to what the US and its UN allies could realistically achieve in Korea. Truman and MacArthur each derived completely different lessons from the Chinese intervention. For Truman, it was clear the idea of unifying the Korean Peninsula under democratic rule was pure folly. Beijing made clear that it would never allow such an outcome and further efforts in that direction only risked escalation and a broader conflict. In Truman’s mind, the time had come to return to the pre-war status quo and to end the conflict honorably. For MacArthur, such an approach was tantamount to surrender. MacArthur essentially believed that World War III had begun in Korea and the U.S. had to wage it.

Truman was looking for was an opportunity to exit the conflict with U.S. credibility in tact and that opportunity came early in the new year. The U.S. Eighth Army had regrouped from the disaster of the previous year and now under the able leadership of General Mathew Ridgway, began a series of offensives at the end of January 1951 to push the Chinese back across the 38th parallel. The PVA, for all its battlefield success, still suffered from an underdeveloped logistics network. In advancing too far south the PVA had outpaced its supply lines, leaving it vulnerable to a counterattack. On March 18, Seoul changed hands a fourth time, as the Chinese retreated back across the 38th parallel. For Truman and his Pentagon and State Department advisers, the time was ripe to press for a negotiated end to the conflict. The pre-war status quo had been restored and prospects for a much better outcome were dim. Moreover, the mood of the American public was souring on the war. A Gallup Poll in March revealed the Truman’s approval rating had slipped to only 22 percent and people began to refer to the war as “Harry Truman’s War” or “Truman’s Police Conflict.”

Meanwhile, MacArthur, who harbored ambitions of being elected President, continued to insist on prosecuting the war to the fullest extent of U.S. capabilities, even at the risk of a broader war with the Soviet Union. As Truman worked to negotiate a peace, MacArthur announced his own terms for ending the fighting. In a public statement, again without getting any clearance from Washington, MacArthur taunted the Chinese for failing to conquer South Korea. He then went on to threaten to attack China unless the Chinese gave up the fight. He also issued thinly veiled criticisms of Truman and his advisers for their peacemaking efforts. It soon became quite apparent to Truman as well as the Joint Chiefs of Staff that MacArthur’s continued challenges to presidential authority posed a direct threat to the principle of civilian control over the military and that he needed to be relieved. On April 5, Republican House Minority Leader Joe Martin read a letter from MacArthur in the House chamber declaring, “There is no substitute for victory.” The letter not only intentionally torpedoed Truman’s cease-fire proposal but now MacArthur was wading in the forbidden territory of domestic U.S. politics. Truman was furious.

Six days later MacArthur was relieved of his command. In a written public statement Truman acknowledged MacArthur “as one of our greatest commanders.” However, he also explained that “military commanders must be governed by the policies and directives issued to them in the manner provided by our laws and Constitution.” In private, Truman was more blunt, remarking, ““I didn’t fire him because he was a dumb son of a bitch, although he was,” Truman later said. “I fired him because he wouldn’t respect the authority of the president.” Public reaction was overwhelmingly against the firing of MacArthur. Tens of thousands of telegrams opposing MacArthur’s dismissal flooded the White House. President Truman himself was booed at a baseball game while MacArthur returned to the United States and was welcomed by huge emotional crowds and a ticker tape parade. Nevertheless, even though Mac Arthur was extremely popular with the public, only 30 percent of the public agreed with his view of escalating the war.

From Stalemate to an Armistice

Truman replaced MacArthur with General Mathew Ridgway, commander of the U.S. Eighth Army, and for the next two years the war settled into a stalemate with no dramatic swings one way or the other, as was indicative of the first year of the conflict. There was still fierce fighting to be sure but neither side made any significant headway. As the stalemate settled in, public opposition to the war grew. In 1952, a politically wounded Truman decided against seeking re-election and General Dwight D. Eisenhower, a Republican, was elected President largely on a promise that he would find an honorable end to the conflict. On the other side there were also huge shake-ups. Stalin died in March of 1953 and there was some concern that the new Soviet leadership might not be as supportive of the Chinese and North Korean war effort. That year the United States successfully tested its first hydrogen bomb increasing its destructive capacity. By July 1953, both sides were worn out by the conflict and on July 27, 1953, North Korea, China, and the United States signed an armistice agreement. South Korea, however, objected to the continued division of Korea and did not agree to the armistice or sign a formal peace treaty. So while the fighting ended, technically the war never did.

Nearly 40,000 American troops, and an estimated 46,000 South Korean troops, were killed. Casualties were even higher in the north, where an estimated 215,000 North Korean troops and 400,000 Chinese troops died. But the vast majority of the dead—up to 70 percent—were civilians. As many as four million civilians are thought to have been killed, and North Korea in particular was decimated by bombing and chemical weapons.

Aftermath

The Korean War has often been called the “Forgotten War” but its importance is huge. The use of US military forces to defend South Korea against communist aggression gave credibility to U.S. security guarantees and reassured our allies that these guarantees were not empty promises on a piece of paper.

The conflict also introduced the concept of “limited war,” which essentially was at the heart of the Truman-MacArthur feud. A limited war can best be defined as a conflict in which the belligerents restrict the purposes for which they fight to concrete, well defined objectives that do not require the utmost military effort of which the powers are capable and that can be accommodated in a negotiated settlement. Up until Korea, the United States was accustomed to fight wars in which all means of national power were used to achieve the enemy’s unconditional surrender. In World War II the United States used maximum force to defeat Nazi Germany and Japan. However, in Korea, the US needed to limit both its objectives and means in order to avoid escalating the conflict into a broader war with a nuclear armed Soviet Union. The concept of limited war without the possibility of complete and total victory was alien to the American public but it would become norm for many conflicts in the nuclear age.

The Korean War also marked a major turning point in US security affairs, serving as the impetus for Eisenhower’s “New Look” defense policy, with its heavy emphasis on strategic nuclear weapons to deter conflicts both conventional and nuclear. Eisenhower understood the need to stop the spread of communism but he was skeptical of the American people’s’ willingness to support future limited wars. He also questioned the wisdom of sustaining such expensive defense budgets. To square this circle, the Eisenhower administration adopted a purely American solution to the problem. It would replace manpower with technology, nuclear weapons. Essentially, the U.S. proclaimed that any attack, no matter how small, would be met with force disproportionate to the original. The Eisenhower administration calculated that the threat of massive retaliation would be sufficient to deter communist aggression. In reality the policy was flawed because it effectively left Eisenhower without any options other than nuclear war to combat communist aggression in the face of “less than total challenges” such as the 1954-1955 Quemoy and Matsu crisis.

Lastly, the frustration and anger over the Korean War affected not only the U.S. public but the military as well. There was a strong feeling in the upper echelons of the U.S. armed forces that Korea, to quote General Omar Bradley, was “the wrong war, at the wrong place, at the wrong time,” and that the United States should “never again” fight a land war in Asia for limited objectives. These officers would be dubbed the “Never Again Club” and would include Army Chief of Staff General Mathew Ridgway who commanded the U.S. Eighth Army in Korea and replaced MacArthur after he was dismissed by Truman. Almost a year after the armistice in Korea was signed the United States found itself on the precipice of another land war in Asia as the French were on the verge of defeat at the hands of the Vietnamese communists and were seeking U.S. military intervention. Serious debate within the Joint Staff occurred regarding the use of AirPower and nuclear weapons to save the French but Ridgway led the fight against intervention arguing that the risks far outweighed the rewards. The power and influence of the “Never Again Club” would ebb by 1960 as the Army suffered from resource cutbacks under Eisenhower’s New Look defense policy and searched for new opportunities to demonstrate its relevance and Vietnam would come to be that opportunity.