On July 28, 1932, U.S. Army troops, under the command of General Douglass Mac Arthur violently dispersed the “Bonus Army”—roughly 30,000 World War I veterans and their families—who had gathered in Washington DC to demand early payment of a bonus they had been promised by Congress for their service. Amidst the worsening economic conditions of the Great Depression, these increasingly desperate veterans and their families travelled from all across the country to Washington DC to press their demand. They came in trucks, old buses, and railroad freight cars. The spectacle of heavily armed troops moving against the unarmed veterans, who had fought for their country years earlier, shocked and disgusted many Americans. It also reinforced the perception, right or wrong, that President Herbert Hoover was indifferent to the suffering of the American people during the depression and it played a significant role in Hoover’s decisive defeat in the 1932 presidential election. This episode would also prove to be a turning point in how our nation treated its veterans, serving as a catalyst for the G.I. Bill and other programs set up for returning veterans in the aftermath of World War II.

In 1926, Congress passed the World War Adjusted Compensation Act, otherwise known as the Bonus Act, over a veto from President Calvin Coolidge. The act promised WWI veterans a bonus based on length of service between April 5, 1917 and July 1, 1919; $1 per day stateside and $1.25 per day overseas, with the payout capped at $500 for stateside veterans and $625 for overseas veterans. The catch was this bonus would not pay out until each veteran’s birthday in 1945, paying out to his estate if he should die before then. Although veterans were allowed to borrow against the bonus certificate beginning in 1927, by 1932, banks were short on credit to give.

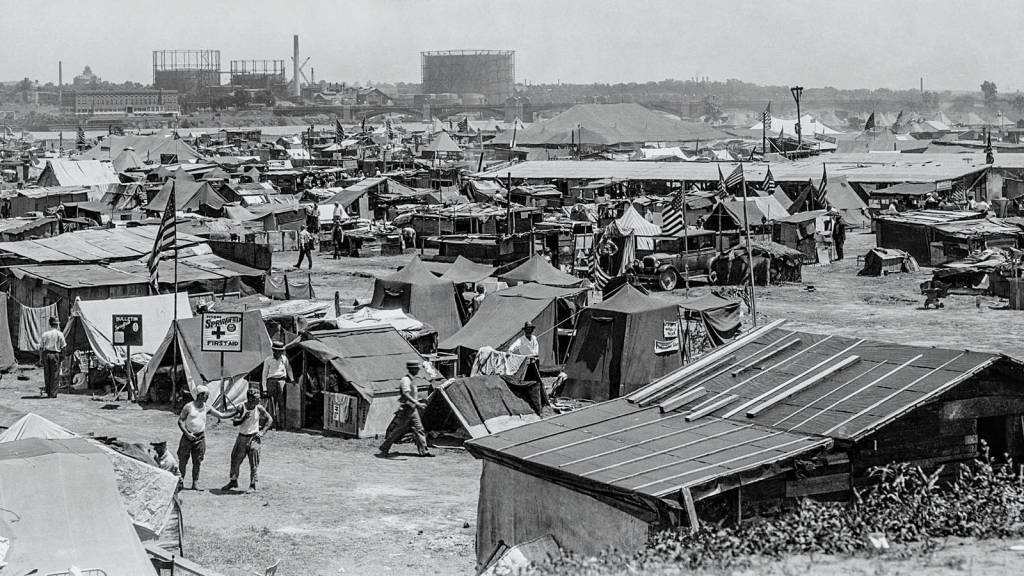

Many of these veterans were now unemployed, broke, and hopeless and began to demand immediate payment to help offset the pernicious impact of the depression. Led by a former Army Sergeant from Oregon, Walter M. Waters, the veterans called themselves the Bonus Expeditionary Force or “the Bonus Army.” They set up camps throughout the city and began to lobby Congress in the spring and summer of 1932 for their bonus. Two camps, in particular, stood out — a group squatting around buildings slated for demolition east of the Capitol on Pennsylvania Avenue, and a larger shanty town in the Anacostia Flats, south of the 11th Street Bridge in what is now Anacostia Park.

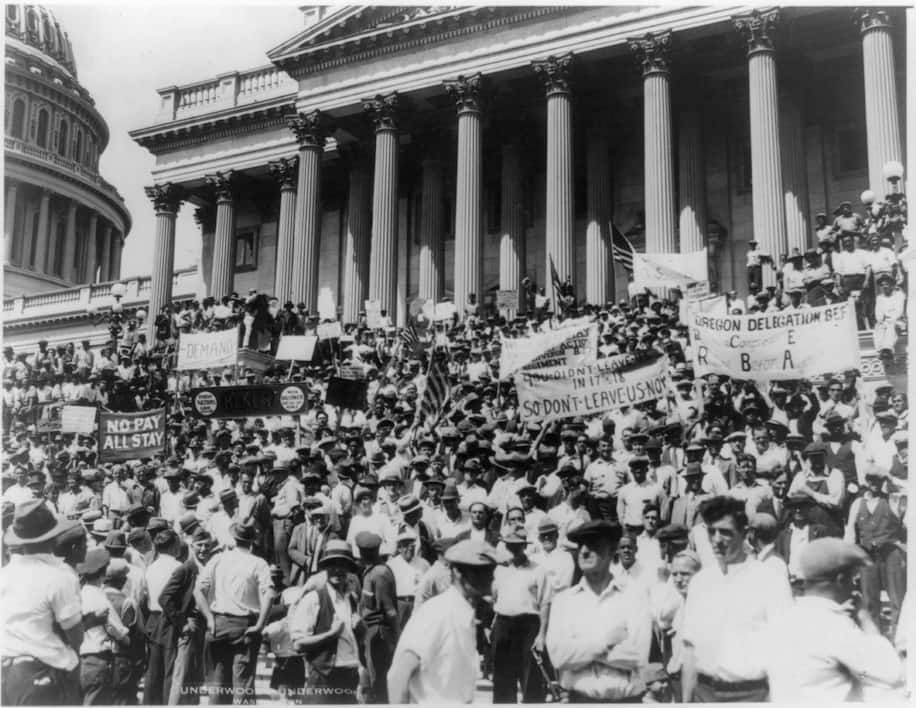

The veterans found themselves a sympathetic supporter in Congressman Wright Patman (D-TX), a WWI veteran himself, who introduced a bill on June 15, to pay the veterans. The bill passed the House of Representatives but was subsequently voted down in the Senate, 62-18, with many Senators claiming the country lacked adequate funds to make the immediate payments that were demanded. With the defeat of the Patman bill, some of the veterans returned home believing their cause to be lost but 20,000 remained. Undeterred, Walter Waters vowed, “We’ll stay here until the bonus bill is passed.” He staged daily demonstrations before the Capitol and led peaceful marches past the White House but Hoover refused to give him an audience.

Unwilling to meet their demands, the Hoover administration disparaged and denounced the veterans as criminals and communist agitators. President Hoover reportedly believed that veterans made up no more than 50 percent of Bonus Army members. In reality, members of the American Communist Party did seek to exploit the situation but they probably represented less than 10 percent of the marchers. A subsequent study conducted by the Veterans Administration revealed that 94 percent of the marchers had Army or Navy service records.

On July 28, the situation turned violent as the city police tried to remove a number of veterans who were encamped along Pennsylvania Avenue. Amidst the ensuing melee, two of the bonus marchers were killed. Fearing that this was the beginning of a larger riot, President Hoover ordered Mac Arthur and the Army to disperse the veterans. That evening, Mac Arthur and about 1,000 troops advanced with tanks, fixed bayonets, and tear gas seeking to drive the demonstrators back across the 11th Street Bridge to Anacostia Flats. Hoover reportedly warned Mac Arthur twice not to cross the bridge in pursuit of the retreating veterans but the General ignored these warnings believing he was suppressing a violent insurrection seeking to overthrow capitalism and the constitution. Mac Arthur continued to advance on the veterans’ camp. The troops drove off the remaining 10,000 inhabitants and set fire to the shanties. The Bonus Army had been dispersed permanently.

Although the operation was a success, the political consequences were disastrous . Hoover defended his use of force against the veterans, declaring, “A challenge to the authority of the United States Government has been met, swiftly and firmly.” However, many Americans were shocked and dismayed by the news and the images of tanks, soldiers with fixed bayonets, and saber wielding cavalry threatening the veterans. Alabama Senator and future Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black denounced the military crack down as an overreaction. “As one citizen, I want to make my public protest against this militaristic way of handling a condition which has been brought about by wide-spread unemployment and hunger,” Black remarked. Senator Hiram Johnson of California, dubbed the incident “one of the blackest pages in our history.” Even the Washington Daily News, which was normally GOP friendly called it “A pitiful spectacle,” to see “the mightiest government in the world chasing unarmed men, women, and children with Army tanks. If the Army must be called out to make war on unarmed citizens, this is no longer America.”

This episode would torpedo Hoover’s re-election bid in 1932, confirming for many Americans that Hoover lacked the leadership skills and bold new ideas to lead the country through the economic crisis. Hoover would go on to lose in a landslide to Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Remnants of the Bonus Army again began to trickle back into Washington DC shortly after Roosevelt’s inauguration in 1933. Roosevelt also opposed meeting the demands of the veterans on the grounds that it would favor a special class of citizen over others at a time when all were suffering. However, unlike Hoover, Roosevelt would take other positive steps to try and ameliorate the economic hardship of the veterans. He would offer them jobs in his new Civilian Conservation Corps and set up Veteran Rehabilitation Camps to help address the unemployment problem. In 1936, Congress finally passed a bill over President Roosevelt’s veto. The Bonus Army had achieved its objective.