On 17 September 1862, Confederate and Union military forces clashed near Antietam Creek in Western Maryland in what would become the bloodiest day in American history. The two armies together would suffer almost 23,000 killed or wounded and places named “the Cornfield,” “Bloody Lane” or “Burnside’s Bridge” would become forever etched in the collective memory of the nation. The outnumbered Confederates under General Robert E. Lee barely escaped a catastrophic defeat that might have ended the civil war two years sooner if it were not for the indecision of Union General George B. McClellan and his over abundance of caution. Lee’s narrow escape would allow the Confederacy to survive another two and a half years and prove the adage that sometimes it is better to be lucky than good.

The summer of 1862 was ending on a high note for the Confederacy after McClellan’s defeat in the Seven Days Battle and an impressive victory at Second Manassas. In Lee’s mind, momentum was on the side of the Confederacy, and it was time to bring the war to the North. It was time to invade Maryland. Although Maryland was a border state, many Marylanders held pro-Southern sympathies, and Lee calculated that a decisive victory on Maryland soil would not only demoralize the Union but bring Maryland into the war on the side of the Confederacy. It also was harvest time, and Lee wanted to take the war out of Virginia so that its farmers could collect their crops to help feed his army. Many of Lee’s troops were underfed and malnourished subsisting on field corn and green apples, which often gave them indigestion and diarrhea, negatively impacting their availability for combat.

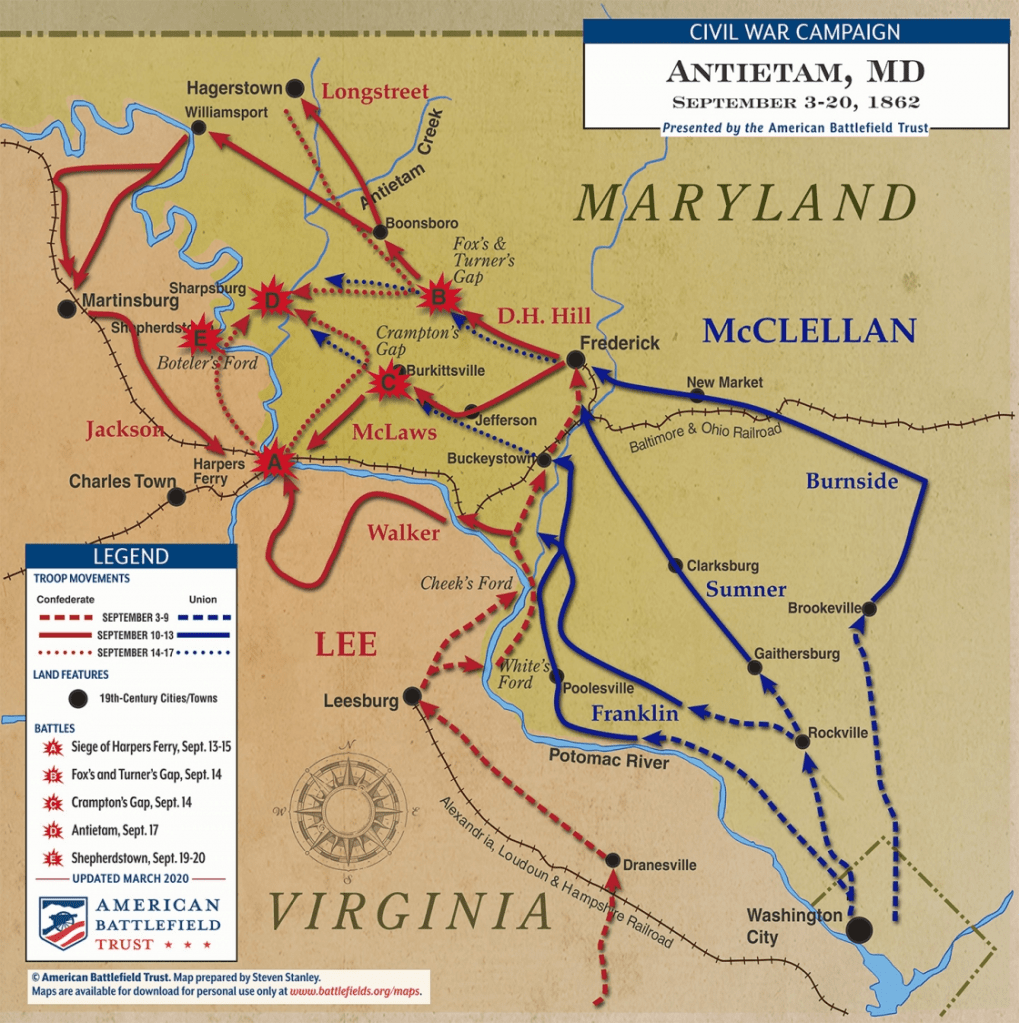

Lee and his 55,000-man army crossed the Potomac River into Maryland on September 4. Three days later his ragged and barefoot army entered the city of Frederick where they encountered an unexpectedly cool reception. Instead of an outpouring of support and affection they found a lack of enthusiasm for their cause if not outright hostility. Several pro-southern citizens of Frederick could not believe that the victorious Confederate army that they heard about was so poorly clad while other stunned citizens just turned their backs. One unnamed citizen noted: “I have never seen a mass of such filthy strong-smelling men.” Lee expected that once he entered Frederick the Union garrisons at Harper’s Ferry and Martinsburg would be withdrawn, clearing the way for him to establish communications through the Shenandoah Valley. Lee could not continue his invasion with these troops sitting on his supply line. He audaciously divided his army and prepared to move deeper into the North while simultaneously seizing Harpers Ferry.

Word that Lee and his army were occupying Frederick prompted McClellan and his 100,000-man army to pursue the rebels. McClellan by nature, was overly cautious. He also consistently overexaggerated the strength of Lee’s army. As a result, his pursuit of Lee lacked the urgency the situation demanded. When McClellan finally reached Frederick on September 12, Lee already divided his army and began to move West. However, McClellan received a stroke of good luck near Frederick when soldiers from the 27th Indiana Regiment discovered a copy of Lee’s orders for the Harper’s Ferry operation, Special Orders no. 191, lying on the ground wrapped around three cigars in a recently abandoned Confederate camp. The discovery of the orders clarified the operational picture for McClellan and revealed that Lee’s army was divided and ripe for defeat in detail.

Now fully aware of Lee’s intentions, McClellan had a simple plan; attack and destroy each element of the Confederate army before it had a chance to reunite. McClellan boasted to Brigadier General John Gibbon of the famed Iron Brigade, “Now I know what to do! Here is a paper with which, if I cannot whip Bobby Lee, I will be willing to go home.” McClellan was determined to seize the initiative and the slowness that characterized his earlier movements disappeared as he raced his army toward the South Mountain range to attack Lee’s army Lee was aware that McClellan was closing in, so after crossing the mountain he sent word to Stonewall Jackson besieging Harper’s Ferry to quickly finish up the task. He also left a rear guard to defend the passes at Turner’s, Fox’s and Crampton’s Gaps to delay McClellan’s and allow time for his army to regroup.

On September 14, advance elements of McClellan’s army engaged Confederate forces guarding the three passes in fierce fighting. The fight would last all day into nightfall and when it was over the Confederates still precariously held two of the three passes. The following day, the Federal garrison at Harpers Ferry surrendered and Lee ordered the forces at South Mountain to withdraw and rejoin the rest of his army near the small town of Sharpsburg. Stonewall Jackson and his men also hurried from Harpers Ferry to rejoin Lee’s army at Sharpsburg, with the exception of General A.P. Hill’s division which remained at Harpers Ferry to prevent Union forces from retaking the town.

Lee had strongly considered breaking off his Maryland Campaign and returning to Virginia but when he received the news of Harpers Ferry’s surrender he decided to remain. He used much of September 16 to reorganize and reposition his army for a battle he knew was coming. In characteristic fashion, McClellan’s innate caution prevented him from taking advantage of an opportunity to crush Lee’s army before it could reunite. McClellan spent much of the two days following the battle at South Mountain drawing up plans instead of vigorously pursuing Lee’s exhausted men. When McClellan did arrive near Sharpsburg, on September 16, he discovered Lee had established a 2.5 mile long battle line behind Antietam Creek. That evening Union and Confederate forces skirmished,McClellan drafted a straightforward battle plan. The next day, his army would strike at each of Lee’s flanks simultaneously, followed by a massive assault on the Confederate center. Even though McClellan’s plan was straight forward, the execution of it was wanting.

The battle began the following morning at daybreak when the first brigades of General Joe Hooker’s I Corps entered the cornfield of farmer David Miller which would become ground zero for the initial phase of the battle. Hooker’s objective was simple, strike Lee’s left flank and drive it back past a small white stone structure known as the Dunker Church. There was no element of surprise to Hooker’s attack. Lee’s men were prepared and when the first Union troops exited the cornfield a brigade of Georgians rose from the ground, from about 200 yards away, and unleashed a withering volley, knocking dozens from the ranks. Thousands of additional Federals were cut down in the tall corn rows and over the next four hours the field would change hands at least six times. Even when reinforcements from General Joe Mansfield’s XII Corps and General Edwin Summer’s II Corps managed to drive the rebels back to the Dunker Church and the West Woods, a vicious Confederate counterattack forced the Federals to withdraw. By mid-morning, both sides together would suffer around 10,000 killed and wounded by the time fighting in the cornfield and West Woods ended.

The focus of the battle soon shifted from the left to the center of the Confederate line. Here two brigades from Alabama and North Carolina occupied a strong defensive position in a fence-lined sunken farm road that would later become known as “Bloody Lane.” The road was worn down from years of wagon use and formed a natural trench for the defenders. Here, over the next three hours, hundreds of Union soldiers, including the famed Irish Brigade, with their colorful green banners, were cut down as they crested a ridge in front of the Rebel defenders. Two Union regiments eventually managed to flank the Confederate line and seized a slightly elevated position that allowed them to pour down a murderous fire upon the rebels. Several brigade and regimental commanders went down and the entire Confederate line began to break under the weight of the attack and a broken command structure. Soon the Confederates were fleeing back towards Sharpsburg with Federals in hot pursuit. With no reserves to commit, First Corps Commander, James Longstreet, masses an artillery barrage that sends the Federals reeling. The situation was so dire that Longstreet and his staff manned one of the rebel artillery pieces. By 1:00 pm, 2500 Confederate dead and wounded lined the sunken road. Union casualties totaled just under 3,000. The fight at the sunken road is a pivotal point in the battle that is the difference between a decisive Union victory and a tactical draw. There are no Confederate reserves left but McClellan grievously overestimated the strength of Lee’s army. Fearing a Confederate counterattack, he declines to deploy his two Corps he has in reserve which probably would have allowed him to cut Lee off from his escape route across the Potomac at Boetler’s Ford.

The final phase of the battle shifts to the Confederate right in the afternoon where a determined Union assault crushes the rebel flank and disaster is only averted by the timely arrival of General A.P. Hill’s division from nearby Harpers Ferry. The key players in this drama were General Ambrose Burnside and his 12,000 strong IX Corps, tasked with rolling up the Confederate flank and cutting off Lee’s retreat, and four undermanned Confederate brigades totaling about 3,000 men standing in his way. The stage is a 12-foot-wide stone bridge crossing Antietam Creek and the rocky high ground on the other side overlooking the bridge that is occupied by 500 Georgians.

Burnside’s battle plan was to storm the bridge while enacting a crossing, miles downstream where the creek was shallow and could be forded more easily. Around 10 am he launched the first out of what would be three attempts, to seize the bridge. At the same time, he ordered one of his divisions South in search of a crossing point at Snavely’s Ford. The first direct attempt to take the bridge was a complete fiasco. The Connecticut regiment leading the attack came under a withering fire from the Georgians occupying the bluff overhead and within 15 minutes the regiment lost a third of its combat strength. The second assault led by a Maryland and New Hampshire regiment was equally ineffective and costly. By this point in time McClellan was growing impatient and pressing Burnside to take the bridge at all costs. Around 12:30 Confederate volleys began to slack off as the Georgians occupying the bluff overhead began to run low on ammunition. Sensing an opportunity, one New York and one Pennsylvania regiment stormed the bridge under a heavy cover of canister and musket fire. With their ammunition depleted and word spreading that Union troops were crossing near Snavely’s Ford the Confederates fell back, allowing the Federals to cross unopposed.

Burnside had finally taken the bridge but failed to advance with the urgency the situation warranted. He spent two hours moving three of his divisions, his artillery, and supply wagons across the creek before resuming the offensive. This delay proved crucial and was one of the key differences between a decisive Union victory and a tactical draw. It provided Lee with time to regroup and reorganize his beleaguered defenses following the collapse of his center and for General A.P. Hill’s division, which was marching from Harpers Ferry to arrive.

Around 4:00 pm Burnside’s IX Corps swept forward in a mile-wide battle line, driving back every thing in its way, as it pushed to cut off Lee’s retreat across the Potomac at Boteler’s Ford. The advance was led by the colorful Zouaves of the 9th New York infantry. Many of Burnside’s men were inexperienced but their umbers dwarfed the limited Confederate troops in this immediate sector. Lee and his staff were trying desperately to rally their broken forces and stave off a rout but just then, in a most dramatic fashion, General Maxcy Gregg’s brigade of South Carolinians, the vanguard of A.P. Hill’s division, slammed into the exposed left flank of Burnside’s army sending it reeling back down the hills and across Antietam Creek. One Union soldier from the 4th Rhode Island Regiment later described Hill’s counterattack, “They were pouring in a sweeping fire as they advanced, and our men fell like sheep at the slaughter.” By 5:30 the battle was over.

In many ways the battle of Antietam is a tale of failed opportunities, primarily on the Union side, and a contrast in leadership. The battle was a tactical draw, but it could have and should have been a decisive Union victory. It is easy to challenge some of the rationale underpinning Lee’s Maryland campaign. One can also question his decision to split his army in the face of a numerically superior enemy. However, in reviewing the course of the battle, one would be hard pressed to find fault with how Lee and the rest of the Confederate high command conducted the battle or could have better employed all the means at their disposal.

Left: Robert E. Lee, Right: Gerorge B. McClellan

The same cannot be said for McClellan who proved woefully inadequate. in his typical self-important fashion, cabled a situation report back to Washington the day after the battle writing, “Those in whose judgment I rely on tell me I fought the battle splendidly and that it was a masterpiece of art.” In reality, he fought the battle not to lose rather than trying win. As a result, he squandered opportunity after opportunity to inflict a decisive and catastrophic defeat on the rebel army. Throughout, the battle McClellan had kept two army corps, between 20,000-30,000 troops, in reserve. He mistakenly feared he was badly outnumbered by Lee and that should he be defeated he would need a reserve force to prevent Lee from moving further North. Had McClellan deployed those reserves in support of the attack on the Sunken Road, Burnside’s efforts to roll up the Confederate right flank, or even to launch a series of new attacks the following day most likely would have resulted in a decisive Union victory and possibly shortening the war by two years. McClellan would pay a steep price for his timidity. Two months later he would be relieved of his command by President Lincoln.