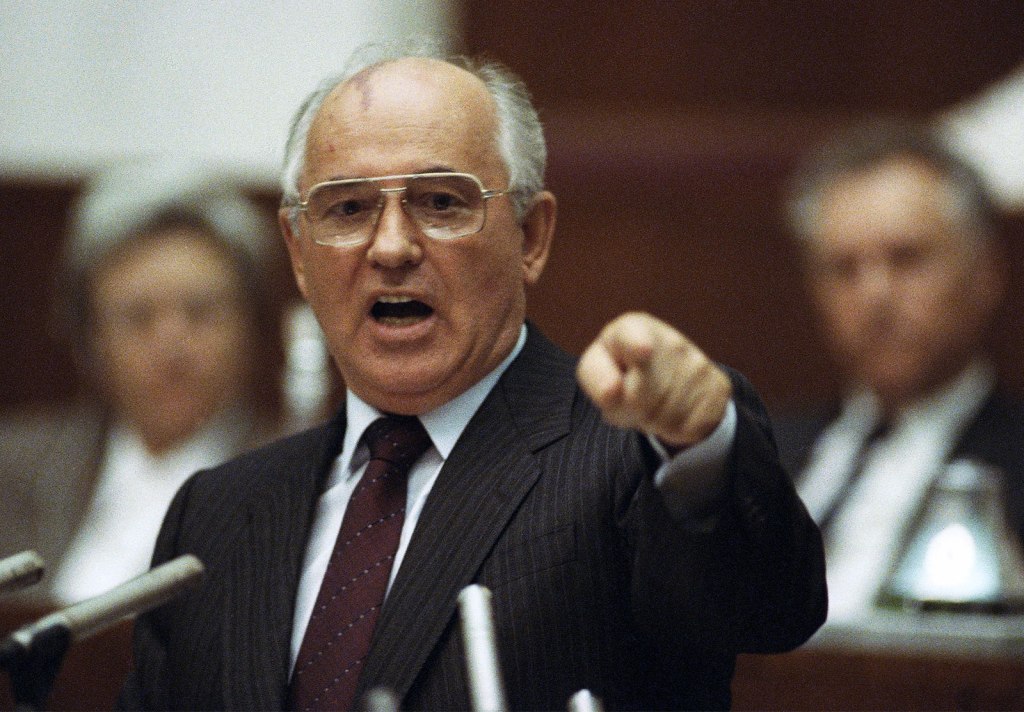

Thirty years ago this week, Soviet hardliners carried out an ill-fated attempt to overthrow Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, seeking to stave off what they perceived as the looming disintegration of the Soviet Union. In doing so, these coup plotters unleashed powerful centrifugal forces, accelerating the outcome they sought to prevent. Four months later, the hammer and sickle flag of the Soviet Union was lowered from the Kremlin for the last time; and with it, the country passed into what Leon Trotsky famously called the “dustbin of history.”

In March 1985, Gorbachev came to power inheriting a country that was clearly at risk of falling behind and badly in need of systemic reform. Gorbachev’s twin policies of Glasnost and Perestroika were largely aimed at reforming the Soviet system to make it more responsive to the needs of the state and the Soviet people. However, instead of revitalizing the country, they would undermine the foundational institutions that kept the system afloat. Gorbachev’s tinkering around the margins of the Soviet command economy always fell short of the structural reforms needed to breathe new life into the system. His “new thinking” in Soviet foreign policy, which was intended to create an international environment more conducive to internal reforms, would lead to a relaxation in Cold War tensions and most importantly the collapse of communist rule in Eastern Europe. However, in the end, all it achieved was to ensure that Gorbachev would be remembered more fondly abroad than at home.

It was Gorbachev’s opening up of the Soviet political system which would ultimately lead to the country’s demise. For decades, Soviet leaders ruled with an iron hand stamping out any dissension or opposition the deemed a threat to their socialist state but such practices also contributed to the overall stagnation of the country. In promoting his concept of Glasnost, which loosely translates into openness, Gorbachev sought to encourage debate and the exchange of ideas that might produce new solutions to the country’s problems, Grant the Soviet people more freedom, and to put a “human face” on the Soviet system by making it less repressive. Instead these reforms raised uncomfortable questions about Soviet history, created new platforms for regime critics and opponents to challenge Soviet central authority, and unleashed pent up ethnic nationalism that undermined the legitimacy of the state and the instruments of coercion that Soviet leaders relied on to keep everything in order.

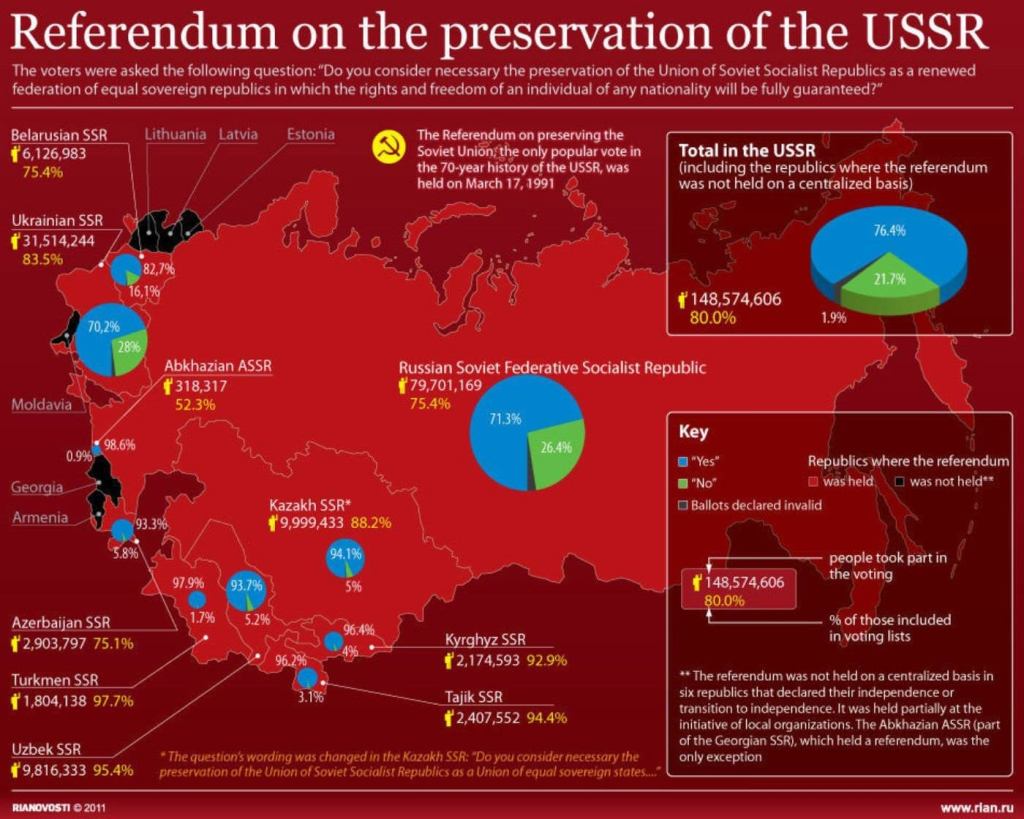

For all intents and purposes, it was the growing demands for independence among the non-Russian Soviet Socialist Republics and Gorbachev’s consent to sign a new Union treaty that would devolve more power and authority to the republics than the center propelled the coup plotters into action. Soviet leaders, much like the Russian Czars, had long seen ethnic nationalism as a threat to the territorial integrity and cohesion of the state and once Gorbachev let this genie out of the bottle, he found it increasingly difficult to push it back in. Unwilling to resort to the large scale use of violence to keep the country together, especially after the fallout from the January 1991 Soviet military crackdown in Lithuania, Gorbachev agreed to hand over more power and authority to the republics as a price to keep the country together.

Determined to stymie any plans for a new Union treaty, the coup plotters moved to detain Gorbachev on the evening of August 18 while at his dacha in Crimea. They demanded that Gorbachev declare a state of emergency or resign and name Soviet Vice President Gennady Yanaev acting President in order to restore order. Gorbachev refused. The following day the coup plotters, now calling themselves “the State Committee for the State of Emergency”, appeared on television and announced that Gorbachev was ill and that they were taking over.

The coup attempt was poorly conceived and executed from the outset but it’s failure was not a foregone conclusion. When the coup conspirators appeared on stage the following day to announce Gorbachev had resigned and they were taking over some were nervous and visibly shaken. For example, Prime Minister Valentin Pavlov was sweating and trembling profusely demonstrating clear signs of hypertension and stress, which did not convey confidence. At the same time the coup plotters failed to arrest President of the Russian republic, Boris Yeltsin, who had become a fierce critic and thorn in the side of the Soviet leadership. The position of the President of Russia was a fairly new one, a direct result of Gorbachev’s reforms, and Yeltsin was using the post to challenge the a legitimacy of the Soviet authorities. KGB Chairman Vladimir Kryuchkov ordered the elite KGB Alpha commandos to surround Yeltsin’s residence. However, Yeltsin and his people had gotten word of what was happening and he fled just before the Alpha commandos arrived.

Hundreds of tanks and armored vehicles poured into downtown Moscow in a massive show of force but the Soviet military was divided in its loyalties, despite Defense Minister Yazov and other senior defense officials being part of the coup. In 1957, the Soviet military played a key role in squashing a move by rival Communist Party officials to oust Khrushchev but the military was not asked to fire on their own people. By 1991, however, the Soviet military had been called on to use violence to suppress domestic unrest in Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Lithuania and there was little appetite within the military to play a greater role in domestic politics. Although there was a clash between some Soviet troops and protestors that left three dead, the military, for the most part, sought to straddle the fence looking for indicators of who was likely to prevail.

Ultimately, Yeltsin proved to be the pivotal figure in this drama. The photo of Yeltsin atop a Soviet tank outside the Russian White House, rallying the resistance to the coup became the defining image of this ordeal. Yeltsin’s courage and leadership would inspire over 200,000 people in Moscow to take to the streets in defiance of the coup plotters. On August 20, the conspirators ordered the KGB’s elite Alpha and Vymple commandos, paratroopers, and OMON forces to storm the White House. These orders were rejected when it was clear these forces were outnumbered and any action would lead to considerable blood shed. Facing unexpected large scale resistance, and unresponsive instruments of coercion, the coup plotters began to lose their nerve and the conspiracy began to unravel.

On August 21, KGB Chairman Kryuchkov and several other conspirators flew to Crimea to meet with Gorbachev to negotiate a way out of the mess they created. Gorbachev refused. That afternoon Defense Minister Yazov ordered all military units to withdraw from Moscow. Around 5:00 pm Yanayev signed a decree dissolving the State Committe for the State of Emergency and it was clear the coup had failed. The following day Gorbachev returned to Moscow and the coup plotters were arrested.

In the end, the coup plotters accelerated the outcome that they so earnestly sought to prevent. Over the next several months, Yeltsin and Gorbachev would battle for primacy as Gorbachev sought to preserve Soviet central authority while Yeltsin tried to seize more power and authority for the institutions of the Russian republic. At the same time, the non-Russian republics increasingly declared their independence from Moscow. The fate of the Soviet Union was ultimately decided on December 1, 1991, when the people of Ukraine voted overwhelmingly in favor of independence. It was now clear that the Soviet Union could no longer be preserved, despite Gorbachev’s best efforts. A week later Yeltsin and the new presidents of Belarus and Ukraine met just outside of Minsk and agreed to dissolve the Soviet Union and replace it with a much weaker and uncertain arrangement, the Commonwealth of Independent States.