On September 24, 1957, President Dwight D. Eisenhower ordered 1,200 troops from the 101st Airborne Division to forcibly integrate Little Rock Central High School in the face of strong public opposition and determined resistance from Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus. These troops would escort nine African-American teens—Minnijean Brown, Elizabeth Eckford, Ernest Green, Thelma Mothershed, Melba Patillo, Gloria Ray, Terrence Roberts, Jefferson Thomas and Carlotta Walls—into the school, forcing a high profile showdown between state and Federal authorities. Although federal troops would clear the way for their entrance that day, “the Little Rock Nine,” would be subject to constant threat, abuse, and harassment the remainder of the year while the state and the rest of the South developed new strategies to avoid desegregation.

Brown v. Board of Education: The Battle Begins

The landmark 1954 Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Eduction, which declared segregation unconstitutional, sent shockwaves through out Arkansas and the rest of the South prompting vows of “massive resistance.” Many Southern states initial impulse was to simply ignore the ruling for as long as possible and slow roll the court-ordered desegregation. However, this strategy became increasingly untenable. Foot dragging on the issue had become so prevalent in the South, the court issued a second decision in 1955, known as Brown II, ordering school districts to integrate “with all deliberate speed.” At the same time, the National Association for he Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) also pressed the issue by registering black students in previously all-white schools in cities throughout the South. In Arkansas, the local chapter of the NAACP carefully selected these nine students who it believed had the intelligence, determination, and fortitude to succeed in breaking the color barrier.

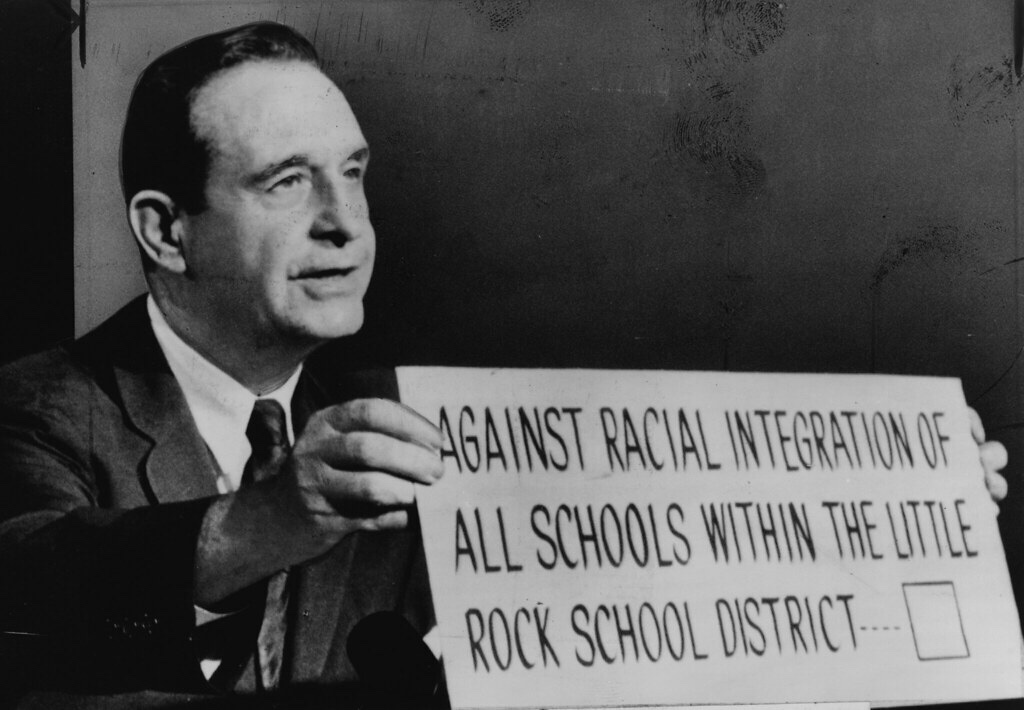

In response to these dual pressures, the Little Rock school board voluntarily came up with a plan for gradually integrating the school system. The first schools to be integrated would be the high schools beginning in September 1957. Among these was Little Rock Central High School where this drama would play out. The school board’s plan was deeply divisive prompting a wave of bitterness and resentment amongst a large swathe of the white community in Arkansas. Two pro-segregation groups formed to oppose the plan: The Capital Citizens Council and the Mother’s League of Central High School.

Blockades and Protests

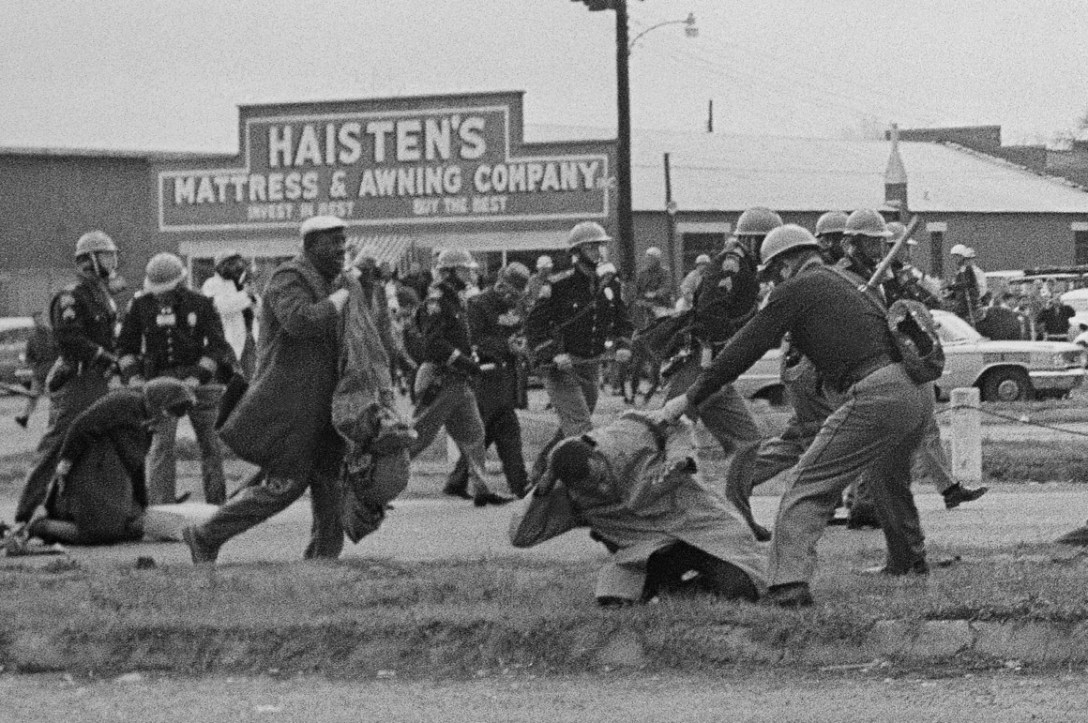

On September 2, 1957 the night prior to what was to be the Nine’s first day in Central High classrooms, Arkansas governor Orval Faubus ordered the state’s National Guard to block their entrance. Faubus said it was for the safety of the nine students warning that violence and bloodshed might break out if black students were allowed to enter the school. On the advice of the school board, the nine African-American students delayed their arrival till the second day, where they encountered a large angry white mob in front of the school, spewing racial epithets, threatening violence and engaging in acts of denigrating behavior. One of the most iconic images of that day was of Elizabeth Eckford, who arrived alone that morning to confront the mob. Eckford, whose family was too poor to afford a telephone, did not get word ahead of time of plans to coordinate their arrival. Eckford was greeted with chants of “two,four, six, eight, we ain’t gonna integrate.” Eckford would recount her experience that day in very stark terms, “They glared at me with a mean look and I was very frightened and didn’t know what to do. I turned around and the crowd came toward me. They moved closer and closer. Somebody started yelling, “Drag her over this tree! Let’s take care of that nigger!”

All nine students were prohibited from entering the school that day in what would prove to be the opening salvo in a much larger battle. Sixteen days later a federal judge ordered the National Guard removed and on September 23, the Little Rock Nine attempted to enter the school again. Though escorted by Little Rock police into a side door, another angry crowd gathered and tried to rush into Central High. Fearing for the lives of the nine students, school officials sent the teens home. They did, however, manage to attend classes for about three hours.

The next day, following a plea from Little Rock’s mayor, Woodrow Mann, President Dwight Eisenhower federalized the National Guard and sent U.S. Army troops to the scene. On September 25, the nine African-American teens entered Little Rock Central High School, personally guarded by soldiers from the Army’s 101st Airborne Division, and began regular class attendance. The Federal government forcibly imposed its authority but the struggle to integrate was far from over. Over the course of the school year, the nine African-American teens were subjected to daily harassment, jeers, and violence at the hands of many white students. For example, Melba Patillo was kicked, beaten and had acid thrown in her face while Gloria Ray was kicked down a flight of steps. At the same time, state authorities regrouped and changed tactics. In September of the following year, Governor Faubus closed all of Little Rock’s high schools for the entire year pending a public vote, to prevent African American attendance. Little Rock citizens voted 19,470 to 7,561 against integration and the schools remained closed for an entire year.

Aftermath

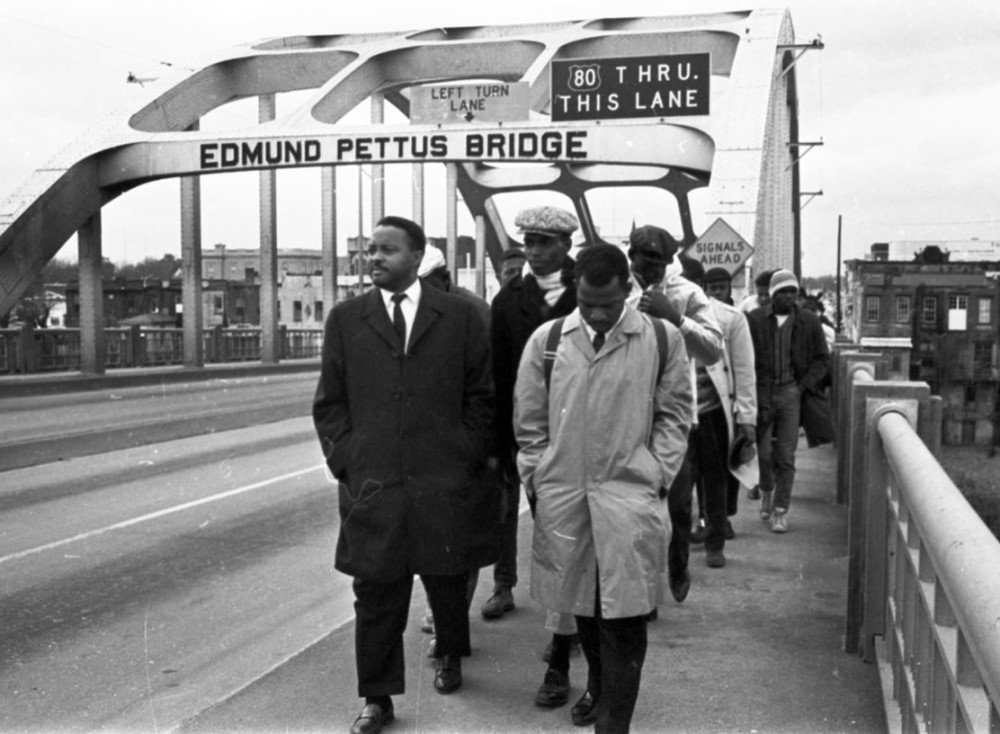

The showdown to integrate Little Rock Central High School was a precursor of things to come through out the entire South over the next decade as white supremacists and segregationists maneuvered to resist integration. Faubus’ use of the national guard and his decision to closed down Little Rock’s public high schools would be replicated by segregationist governors in Mississippi, Alabama, Virginia, and elsewhere. In September 1962, the small university town of Oxford Mississippi was turned into a war zone as Federal Marshals battled with violent white supremacists mobs seeking to prevent African-American James Meredith from attending the University of Mississippi, in what would become known as the “Battle of Oxford.” A year later Alabama Governor George Wallace personally stood in the doorway to the registrar at the University of Alabama to stop African-American Vivian Malone Jones from attending. In Virginia, Prince Edward County would close down its public school system from 1959-1964 rather than comply with court-ordered integration.