On August 27, 1776, British Redcoats routed General George Washington and his fledgling Continental Army at the Battle of Long Island, paving the way for the seizure of New York City which the British would hold until the end of the Revolutionary War in 1783. The battle was the first major engagement for the Continental Army following its creation on June 14, 1775 and its inexperience and lack of discipline showed. The scale and scope of the defeat raised serious doubts about whether Washington was the right person to command the army and nearly ended the American experiment in independence and self-governance before it began

In the Spring of 1776, optimism and patriotic fervor was on the rise throughout the thirteen colonies. British military forces had been forced to vacate Boston and given the blood spilled at Lexington and Concord and Bunker Hill, it was clear there was no turning back. Political discourse no longer centered around a redress of colonial grievances but increasingly focused on full-fledged independence from Great Britain. The will for independence was certainly there, as evidenced by the promulgation of a Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia on July 4. The question remained, however, whether the colonist could win their freedom, let alone keep it, for Great Britain was not about to let them go without a fight.

After British troops were forced to withdraw from Boston to Nova Scotia, all eyes turned to New York City, where it was expected that British would try to return and occupy the crucially important city, with its strategic location and deep sheltered harbor. In April, Washington raced his 19,000 man Continental Army to New York City ahead of the British. However, he quickly recognized that defending the city was nearly impossible. The city consisted of three islands—Manhattan, Staten Island and Long Island— and all of their shorelines were suitable for an amphibious landing which made it difficult to predict where exactly the British might land. Moreover, the Royal Navy’s ability to control the rivers and water ways that cut through New York City would allow British warships to bring their heavy guns to almost any fight. Writing to his brother John, Washington offered a blunt assessment of the situation: “We expect a very bloody summer at New-York … and I am sorry to say that we are not, either in men or arms, prepared for it.”

The first British warships were sighted near Sandy Hook, New Jersey, on June 29, 1776, and within hours, 45 ships would drop anchor in Lower New York Bay. One American soldier was so awed by the fleet, he declared that it looked like “all London afloat.” Of these ships were some of the most powerful in the Royal Navy such as the 64-gun Asia and the 50-gun Centurion and Chatham. The guns on these ships alone outnumbered the combined firepower of all American shore batteries. On July 2, British troops began to land on Staten Island. By mid-August, the British fleet numbered over 400 ships large and small, including 73 warships and 8 ships of the line, while the army had grown to 32,000, more than the entire population of New York City.

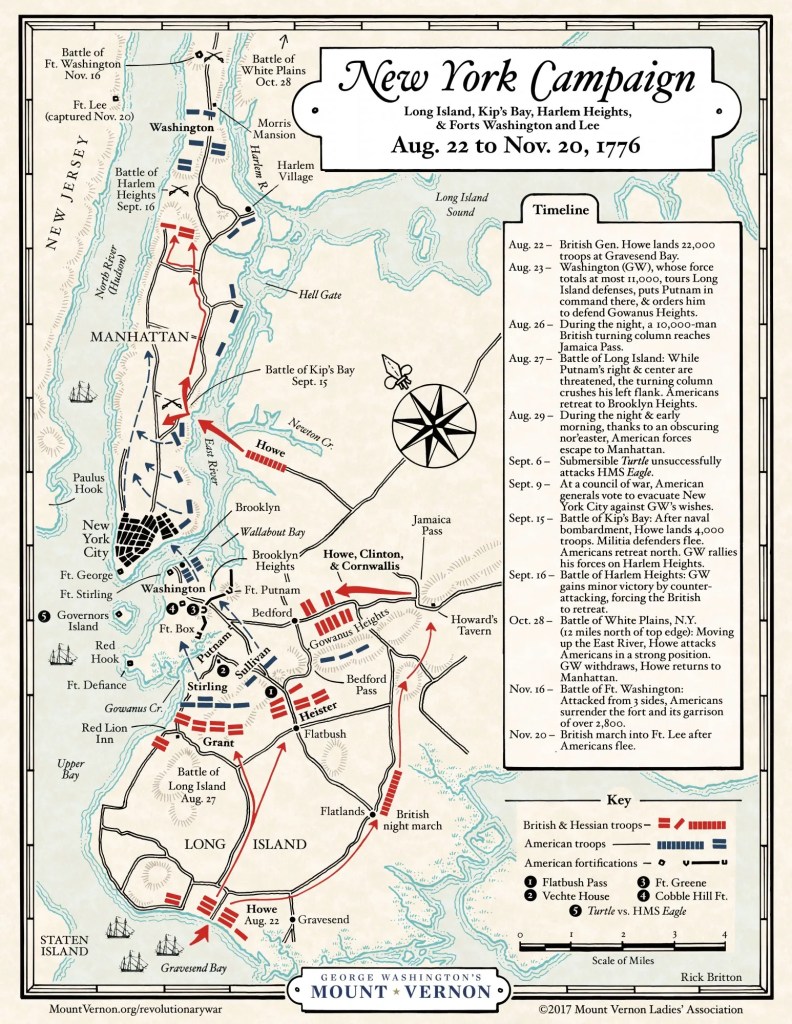

On August 22, 20,000 British and Hessian troops departed Staten Island and made an amphibious landing at Gravesend Bay on the southwestern shore of Long Island. Washington had built fortifications and deployed half his army here in anticipation of a British landing. General William Howe was in overall command of all British troops. However, the battle plan was conceived of by his second in command, General Henry Clinton. Clinton’s plan was to split the army into three divisions. Two divisions would make feints directly against the Americans entrenched on the wooded hills of the Gowanus Heights. The largest division, 10,000 men personally under Clinton’s command, would make an overnight march through an unguarded pass on the left of the American line and turn their flank by surprise.

As the battle commenced in the early morning hours of August 27, the British executed their plan flawlessly and with great success. One division of British regulars under General James Grant and one of Hessian mercenaries under General Leopold Phillip von Heister kept the American defenders fixed and distracted as Clinton maneuvered to turn their flank. Around 9 am, the British sprung their trap as Clinton’s Division reached Bedford village behind the American line and engaged the defenders. At the same time, the two other divisions now turned their feints into full-fledged attacks. With bayonets fixed, the Hessians charged the American left under General John Sullivan and fighting descended into vicious hand to hand combat as the Hessians ruthlessly butchered the Americans. The inexperienced Continentals were now caught between a hammer and an anvil and in danger of being cut off from their route of retreat. Recognizing the danger of their situation, Sullivan’s men panicked and fled pell-mell towards their fortifications at Brooklyn Heights.

With the American left flank disintegrating before their eyes, the American right now began to feel the full weight of Grant’s attack. General William Alexander and his brigade put up stiff resistance for two hours, but the collapse of the American left put his brigade’s position increasingly in peril. Threatened with encirclement, Alexander ordered his brigade to fall back. He personally led 250 Marylanders in a bayonet charge against an overwhelming British force creating a crucial window of time for more of his soldiers to escape to their fortifications in Brooklyn Heights. Alexander was eventually taken prisoner and only nine of the original 250 made it to the safety of Brooklyn Heights. Watching the battle on the right unfold, Washington remarked “Good God, what brave fellows I must lose.”

By noon, the battle had largely ended. But when the dust cleared the total number of Americans killed, captured, and wounded reached nearly 2200. Although Washington managed to survive a catastrophic day, he wasn’t out of danger yet. His army remained divided between Manhattan and Long Island and the portion that remained on Long Island was exhausted and penned up, with Howe’s army in front of it and the East River at its back. On August 29th, Washington made the unavoidable decision to withdraw his troops from Brooklyn Heights. That evening, under a cover of darkness and fog, a Massachusetts regiment composed of mostly sailors and fishermen ferried the endangered troops back across the East River on flat bottom boats to the temporary safety of Manhattan.

Washington’s defeat opened the door to a series of equally disastrous losses that ultimately allowed the British to seize full control of New York City. On September, 15, the Americans were routed again at the Battle of Kipp’s Bay as British troops established a foothold on Manhattan Island. Washington would score a minor victory at the Battle of Harlem Heights the next day but suffer another ignominious and demoralizing defeat at White Plains on October 28. Three weeks later American forces were driven from Forts Washington and Lee giving the British full control of New York City. Washington and his army retreated into New Jersey and were chased across the Delaware River into Pennsylvania. The almost uninterrupted progression of defeats in the summer and fall of 1776 squelched much of the optimism from earlier in the year and cast grave doubt on the viability of the revolution and George Washington’s competency as a military commander. Only Washington’s bold decision to cross the icy Delaware River on Christmas night and wage a surprise attack on the Hessian garrison at Trenton would restore faith and optimism in the cause and tamp down doubts about his suitability uas a military commander.