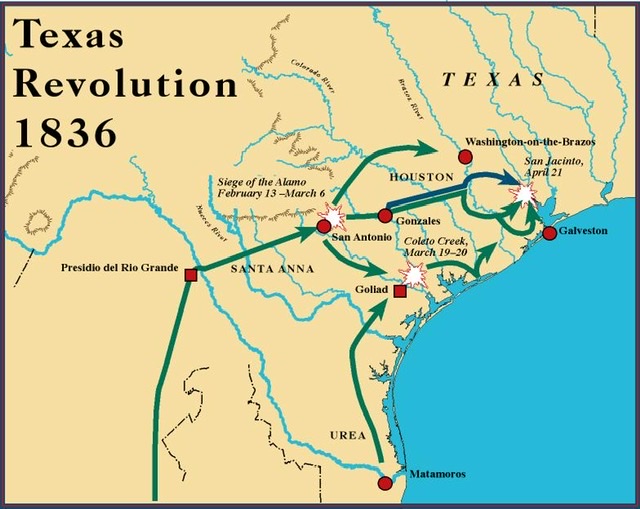

On March 6, 1836, two thousand Mexican soldiers under General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna stormed the isolated Franciscan mission near San Antonio known as the Alamo, killing all 189 defenders inside who were fighting for Texas’ independence from Mexico. The short war for Texas independence, which began the previous October, would conclude successfully a little over a month later on April 21 at the battle of San Jacinto River. There a Texas army under General Sam Houston routed the Mexican Army, capturing Santa Anna whom they agreed to release in return for Texas’ independence. For roughly nine years, Texas would exist as an independent Republic until its annexation by the United States in 1845. The annexation of Texas put into motion a series of events that would lead to the Mexican-American War in 1846. Victory in the war substantially increased the size of the United States, with the addition of California and the southwest, but it also intensified the national debate over the expansion of slavery, unleashing the centrifugal forces that would later result in the Civil War.

In the 1820s, American citizens immigrated to the Mexican controlled territory of Texas, or what was called Coahuila y Tejas, lured by the promises of open land and new economic opportunities. Mexico had just won its independence from Spain several years earlier and was badly in need of settlers to inhabit the sparsely populated Texas territory and guard against marauding Comanche indians. Under, Spanish rule, Mexico had recruited “empresarios” who brought settlers to the region in exchange for generous grants of land. Newly independent Mexico continued this practice and passed colonization laws designed to encourage immigration. Thousands of Americans, primarily from the slave states of Tennessee, Kentucky, Arkansas and Missouri, flocked to Texas and quickly came to outnumber the Tejanos, the Mexican residents of the region. The soil and climate offered good opportunities to expand slavery and the cotton kingdom. Land was plentiful and offered at generous terms. Moreover for many Americans, it was their manifest destiny and patriotic duty to populate the lands beyond the Mississippi River, bringing with them American slavery, Protestantism, culture, laws, and political traditions.

Many of these American immigrants never shed their American identity or loyalty to the United States. For most of these settlers, Texas was an economic venture and deep down inside they showed little interest in Mexican culture or being part of Mexico. Many refused to convert to Roman Catholicism which was usually part of the deal for land grants, and repeatedly ignored Mexico’s prohibition on the public practice of other religions. Mexico’s prohibition of slavery in 1829 also became a source of discontent. Even though the Mexican government was lax in exercising its anti-slavery prohibitions, many of the slave holding settlers were distrustful of the Mexican government and wanted to be a new slave state in the United States. In fact there were those who felt an independent Republic of Texas in which slavery was firmly rooted and recognized was preferable to remaining part of Mexico with an uncertain future for slavery. Lastly, there was also great dissatisfaction among the American settlers with the Mexican political and legal system which was increasingly unstable, unresponsive and dictatorial. Most American settlers were from the frontier states and were Jacksonian-Democrats who firmly believed in “Manifest Destiny” and the philosophy that the best government was the least government.

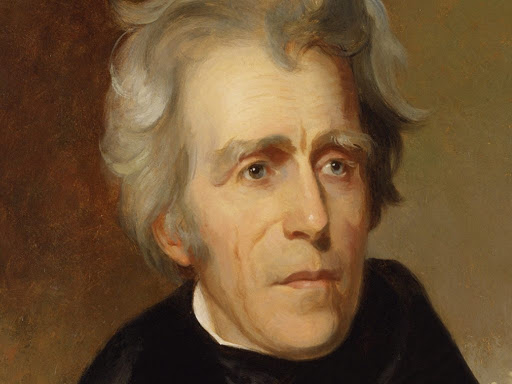

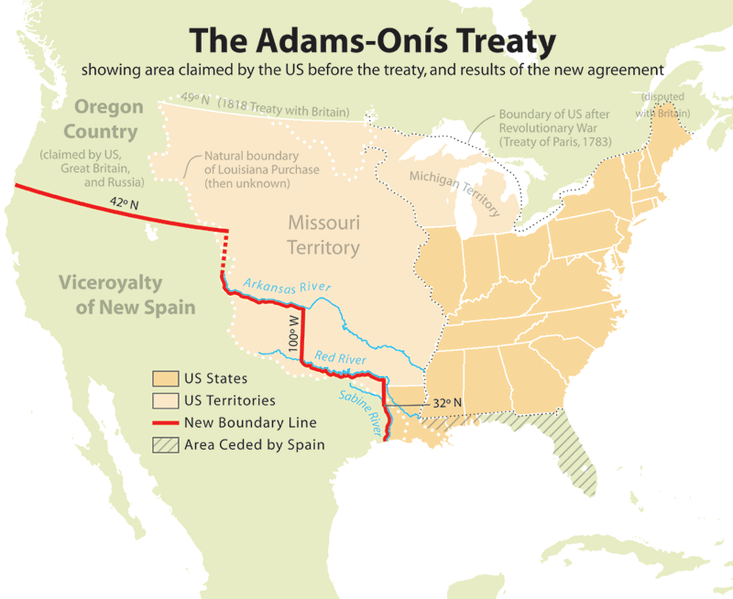

By 1830, American settlers in Texas outnumbered Mexicans by roughly 20,000 to 5,000. Their growing numbers and their refusal to assimilate and follow Mexican law alarmed the Mexican government which proceeded to prohibit any further American immigration to Texas and increased its military presence there. Moreover, there were growing suspicions inside the Mexican government, that the United States deliberately was fomenting discontent among the Texans with an eye toward annexing the territory. President Andrew Jackson harbored a deep and abiding interest in acquiring Texas. Jackson fervently believed that Texas had been acquired by the United States as part of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 but had been recklessly thrown away when President John Quincy Adams negotiated the Florida treaty with Spain in 1819 and agreed to the Sabine River as the western boundary of the country. All these factors pointed to trouble on the horizon.

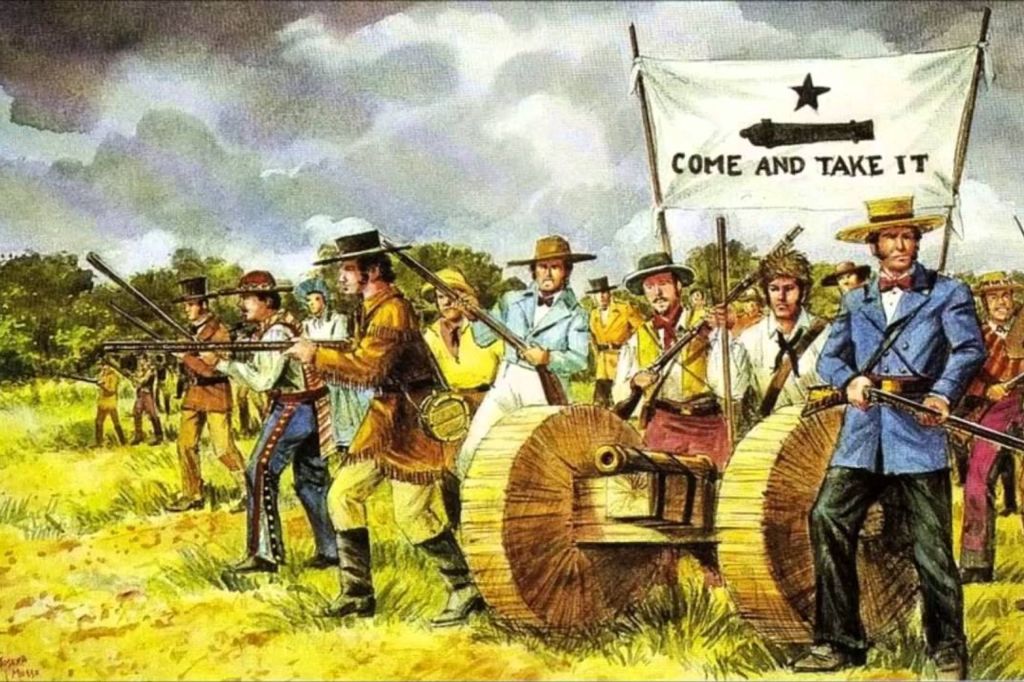

In 1835, General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna seized power in Mexico after a period of prolonged political instability. Santa Anna’s power grab provoked revolts in several Mexican states, including Texas. With relations between the Mexican government and the Texans deteriorating, Santa Anna gave orders to disarm the Texans. On October 2, 1835 a company of Mexican soldiers attempted to seize a small 6-pound cannon that had been given to the town of Gonzales (50 miles east of San Antonio) in 1831 to help defend against Indian attacks. Proudly displaying a homemade white banner with an image of the cannon with the words: “COME AND TAKE IT,” the residents attacked the Mexican troops forcing them to retreat. The incident became the opening salvo in the Texas Revolution.

Having thrown down the proverbial gauntlet, the Texans soon realized that the insurgency could not be sustained without an army and the proper governing institutions As news of the outbreak of hostilities spread, volunteers rushed to join the men at Gonzales and the nascent Texas Army was born. A provisional government soon followed. In the weeks and months following the Battle of Gonzales, the Texans fought several small victorious engagements against their Mexican foe. Arguably most important of these victories took place in early December when 300 Texans under Ben Milam drove a larger Mexican force from San Antonio, setting the stage for the dramatic events at the Alamo the following March.

The tide began to turn against the Texans in the new year. Santa Anna declared that the Texas colonists were in rebellion and that he would personally lead an expedition against them. He assembled a large army and moved north determined to mercilessly quash the rebellion and send a warning to all those who would oppose his rule. In February 1836, he crossed the Rio Grande river with over 6,000 troops and marched toward San Antonio. Here the Texans had inflicted a humiliating defeat on the Mexican army two months earlier and where a group of Texans was now occupying the Alamo. About the same time, another Mexican force under General Jose de Urrea advance north toward Goliad to attack another force of Texans under Colonel James Fannin.

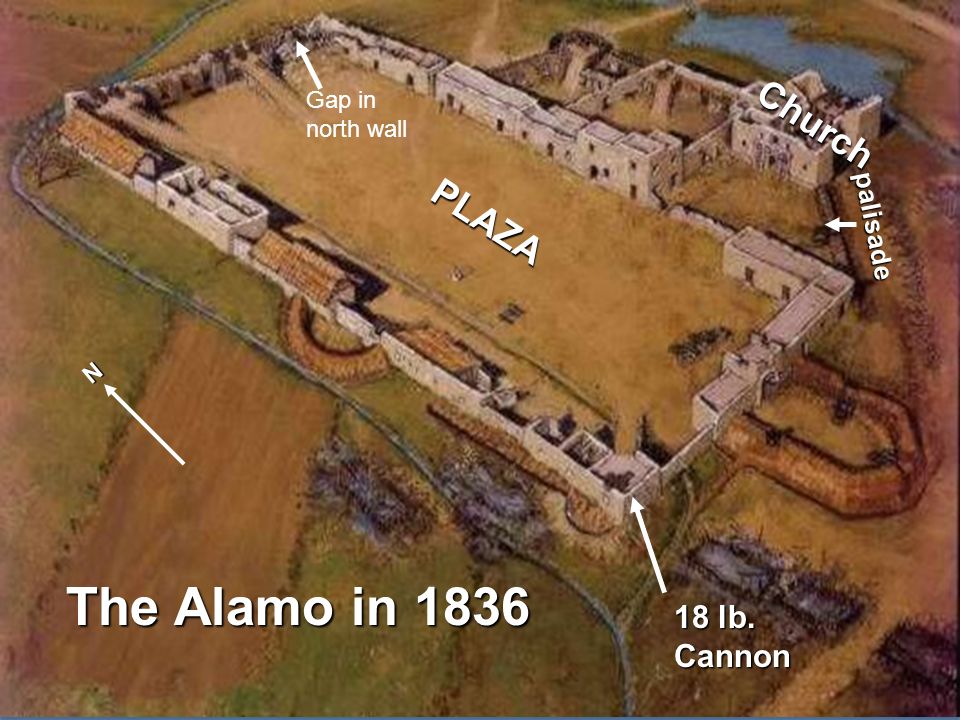

The Texan victory at San Antonio the previous December was an important one bolstering the morale of the fledgling army, demonstrating the righteousness of their cause and capturing much needed arms and supplies. However, it also provided a number of challenges for Major General Samuel Houston, the new head of the Texan Army. San Antonio was relatively isolated and difficult to defend. Moreover, the Alamo, where the Texans had deployed about a hundred men was of limited defensive value. Described by Santa Anna as an “irregular fortification, hardly worthy of the name,” the Alamo was designed to withstand an attack by Indians and bandits, not an army equipped with artillery.

In January 1836, the commander of the Texan forces at the Alamo, Colonel James C. Neil, petitioned General Houston for additional forces to strengthen his defenses. Houston believed that San Antonio was of dubious strategic value and was reluctant to spare any additional troops, He sent Colonel Jim Bowie with 30 men to the Alamo to evacuate the twenty one artillery pieces that had been seized at the battle two months earlier and to destroy the compound. Unfortunately, a lack of draft animals prevented Bowie from completing his task as ordered. Neil managed to convince Bowie of the strategic importance of the Alamo and persuaded him and his men to stay and defend the mission. On February 2, Bowie sent a letter to Governor Henry Smith and the provisional government asking for more men and arms to defend the Alamo. In the letter Bowie wrote, “Colonel Neil and myself have come to the solemn resolution that we will rather die in these ditches than give it up to the enemy.” Despite Bowie’s impassioned plea, few reinforcements were authorized. Smith dispatched Colonel William Travis with 30 cavalry men to go to the Alamo. Soon after, another small group of volunteers arrived, including the famous frontiersman and former Congressman David Crockett of Tennessee.

The Alamo defenders now numbered around 150 men but more were clearly needed. On February 11, Neill departed the Alamo to attend to a family emergency and to seek out additional reinforcements. Before leaving, he transferred command to Travis, the highest-ranking regular army officer in the garrison. Neil’s departure created a temporary leadership crisis. Volunteers made up much of the force and they balked at accepting the more bookish Travis as their leader. Traditionally, volunteers elected their leaders and the men instead chose Bowie, who had a reputation as a fierce fighter, as their commander. Travis and Bowie quickly resolved the problem by agreeing to a joint command structure until Neill’s expected return. However, illness would incapacitate Bowie and Neill never made it back, leaving Travis as the sole commander.

On February, 23, 1836, Santa Anna and his army arrived in San Antonio and began preparations for a siege. Santa Anna ordered the raising of a blood red flag atop the San Fernando Church, sending a clear message to the Texans to expect no quarter. Significantly outnumbered, the Texans pressed the Mexicans for terms of surrender but were quickly told the only acceptable terms were unconditional surrender. If there were any doubts among the Alamo defenders that this would be a fight to the finish, they were quickly dispelled.

Santa Anna methodically encircled the Alamo and bombarded the fort with his artillery. Each night he tightened the noose, gradually moving his batteries closer towards the walls. The Texans responded in kind with equal ferocity but within three days they were ordered to conserve powder and shot and were ultimately reduced to reusing Mexican cannonballs. For thirteen days, (February 23–March 6) the Texans would steadfastly hold their position behind the walls, resigned to their fate, as they patiently waited for the inevitable Mexican assault.

The situation inside the Alamo grew increasingly dire with each day but the defenders still held out hope that reinforcements would come to their rescue. Travis sent out couriers with desperate pleas to Fanning and his men at Goliad and the other Texans at Gonzales to come to their aid and break the siege. “I call on you in the name of liberty, of patriotism and everything dear to the American character, to come to our aid with all dispatch… if this call is neglected, I am determined to sustain myself and die like a soldier who never forgets what is due his honor and that of his country,” Travis wrote. On March 1, a group of 32 men from Gonzales slipped through the Mexican lines and into the Alamo bringing the defenders numbers to just under 200. The arrival of these reinforcements, although small in number, gave Travis hope that others might heed his call. Unfortunately, these were the last reinforcements that would arrive.

The Point of No Return

Santa Anna called a council of war on the evening of March 4 and announced they would attack the Alamo early on the morning of March 6. His officers were stunned by the sudden announcement. Many preferred to continue the siege for at least another week, believing the enemy was nearing submission. However, Santa Anna was determined to storm the Alamo. A crushing victory over the Texans would send a loud and clear message to any other insurgents and avenge the Mexicans defeat from the previous December.

In the early morning hours of March 6, Santa Anna’s men crept within musket range of the Alamo and hunkered down waiting for the signal to begin the attack. Four columns of 400-500 men each would attack the four walls. The first column would attack the west wall, the one closest to town. The second was assigned the shorter north wall. The third column would attack the rear of the fort from the East. The last would assault the main gate at the south end of the fort. A fifth column would be held in reserve while the Cavalry would cut off any escape.

At 5:30 am, a lone bugle sounded and the four columns commenced the attack. In the background, Santa Anna’s band played the “Deguello,” or “cutthroat” tune signaling no prisoners would be taken. As the troops rushed forward with muskets, ladders, and other implements to scale the walls and break down the doors of the Alamo, they cried out “Viva Santa Anna! Viva Mexico!” The noise of the attack awoke the Texans and they raced to the walls to repel the assault. The first charge was beaten back as the Texans fired improvised grapeshot—broken horseshoes, nails, chain links, and other scrap metal—into the advancing columns. No Mexican soldier got within 10 yards of the wall. The attackers regrouped for a second charge, which was also beaten back as the Texans demonstrated themselves to be equally adept with the musket.

Santa Anna ordered his reserves to join the third assault. By that time the northwest corner of the wall had been breached by cannon fire and Mexican forces poured through the gap and into the interior of the fort. Colonel Travis was shot in the head and fell dead trying to rally his men and expel the Mexican invaders. Batteries defending the south wall quickly pivoted and fired on the new threat from the rear. This allowed the Mexican attackers to scale the southern wall unimpeded and breakdown the doors of the Alamo.

The plaza of the Alamo was now teaming with Mexican soldiers and fierce fighting was now going on inside the fort, much of it hand to hand as the Texans used their muskets as clubs to beat back the Mexicans. Davey Crockett probably fell at this stage of the fighting but some battle accounts claim he was captured and executed at the end of the battle. Some of the defenders tried to fall back to the long barracks and chapel which earlier had been made ready for a last stand, with sandbags and loaded shotguns inside. However, those defending the west wall were now cut off and could not reach these rendezvous points. They fled from the Alamo but were cut down by the Mexican cavalry outside the fort.

Santa Anna’s men now turned to clearing the Texans from these strongholds inside the Alamo. Here an awful carnage took place as the sheer numerical advantage of the Mexican Army proved too much for the Texans. In some of the bloodiest hand to hand fighting, the Mexicans bayoneted and pummeled their way through the rooms of the barracks, giving no quarter. Here Colonel Jim Bowie, bed-ridden with Consumption, met his demise. According to legend, Bowie died fighting from his cot with two pistols in hand and his legendary knife. Roughly a dozen remaining Texans were holed up in the chapel manning two 12 pounder cannons. As the Mexican soldiers entered the building the Texans unleashed a volley from the cannons. With no time left to reload, the attackers surged through the splintered doors and didn’t stop shooting or stabbing till all resistance ceased.

From Disaster to Independence

The entire battle lasted no more than 90 minutes and at the end of it, Santa Anna had his decisive victory. The general proved to be a man of his word. Not a single Texas fighting man was spared. Around 200 Texans lay dead in and around the Alamo including three of the best known figures in the rebellion, Bowie, Travis, and Crockett. Santa Anna did release a number of women, children, and slaves and sent them back to Gonzales to tell the other Texans what happened at the Alamo. News of the Alamo calamity did have a chilling effect but the sacrifice of Travis and his men animated the rest of Texas and kindled a righteous wrath for revenge that would keep the insurrection alive.

Though Santa Anna had his decisive victory, it wasn’t without significant cost to his army and his larger campaign. Accounts vary, but best estimates place the number of Mexicans killed and wounded at about 600. Many were veteran soldiers from his best battalions. Privately, many of his officers despaired at what they viewed as a reckless waste of life and were disillusioned with Santa Anna’s leadership. Many still believed that victory could have been won with less loss of life had they continued with the siege.

With the fall of the Alamo and the subsequent massacre of Texan forces at Goliad two weeks later, Santa Anna still needed to hunt down General Houston and the rest of the Texan army to quash the rebellion. Dividing his army into three, Santa Anna doggedly pursued Houston into East Texas but the rebel general refused to give battle, strategically retreating further East instead. Houston understood that his army was the last hope for an independent Texas and that he needed to use it wisely. He knew that it lacked the necessary training and discipline and that he needed time to train them better. He also wanted to face Santa Anna on ground of his choosing, ground that would offer the Texans the advantage. Nonetheless, Houston’s repeated retreats were taking their toll on the rank and file of his army. Many were tired of retreating. They grumbled Houston was a coward and wanted an opportunity to avenge the tragedies at the Alamo and Goliad. Discontent, however, came not only from the ranks, but from the provisional government as well. Houston was strongly criticized by President of the Texas Republic, David G. Burnet, as well. Burnet wrote to Houston: “The enemy are laughing you to scorn. You must fight them. You must retreat no further. The country expects you to fight. The salvation of the country depends on your doing so.” Houston was not one to be bullied or forced into actions he believed imprudent. He continued to wait for the right opportunity.

On April 18, the Texans intercepted a Mexican courier carrying intelligence on the locations and future plans of all of the Mexican troops in Texas. Houston now knew that Santa Anna was isolated and his army was smaller than anticipated. Feeling confident that the time had come to take to the offensive, Houston prepared his army to attack the Mexicans near the San Jacinto River. On the morning of April 21, Houston gathered six of his top officers together to strategize and lay out their options. Two of the officers suggested attacking the enemy in his position; the others favored waiting Santa Anna’s attack. Houston withheld his own views at the council but he was determined to attack Santa Anna. He had favorable ground. Santa Anna’s men were pinned in a triangle between a bayou and the San Jacinto river, with nowhere to retreat. Moreover, Even though Santa Anna had the edge in terms of numbers, his force was not decisively larger as was the case at the Alamo. Perhaps most important of all he risked losing the confidence of the men he commanded if he failed to act.

By that afternoon, Houston developed a simple plan for battle. He organized his army into three groups. The main attack would strike Santa Anna’s army from the front while the other two groups of forces circled around the left and right flanks of the Mexican camp. Around 3:30, Houston ordered his men to form up. His main body advanced forward undetected, concealed by the terrain, until they were within a quarter of a mile of the Mexican Army. The only two artillery pieces in Houston’s army were moved forward to support the impending attack. At 4:30, Houston ordered his cannons to open fire with grape and canister, a signal to commence the attack. His infantry and Calvary poured out of a tree line and charged forward screaming, “Remember he Alamo! Remember Goliad!

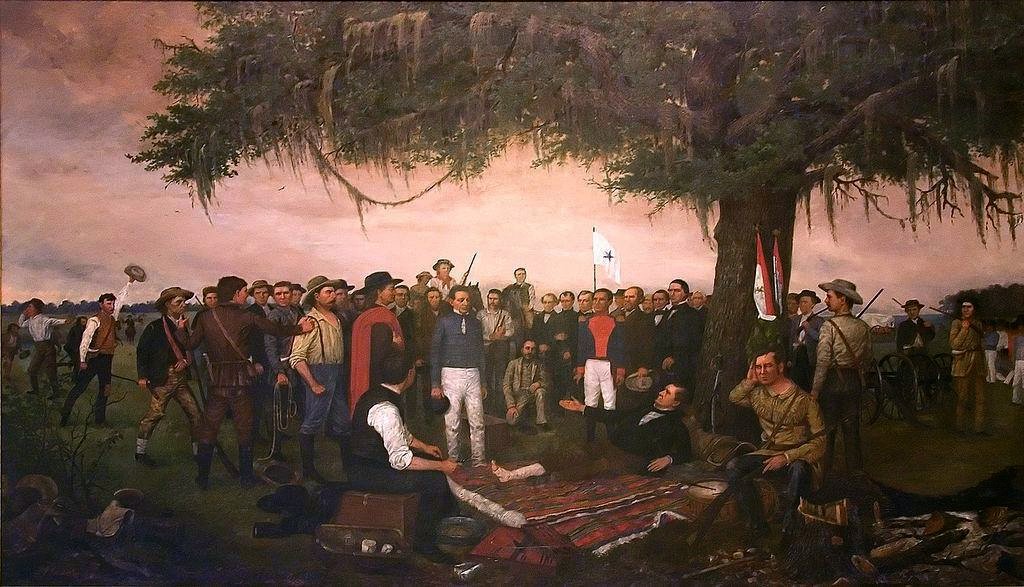

Santa Anna had been concerned that the Texans might strike his army earlier in the day but an attack so late in the day took him completely by surprise. Santa Anna concluded, not unreasonably, that Houston was not going to attack that day and allowed his men to relax and get much needed rest. Even the general himself had fallen into a deep sleep only to be woken by the clamor of the Texans’ assault. The entire Mexican Army fell into a panic as the Texans surged forward. Some Mexican officers and their men tried to make a stand but were overwhelmed. Most simply threw down their weapons and fled, driven into the bayou or the lake, including Santa Anna himself. Enraged Texans shot or bayoneted scores, in retaliation for the Alamo and Goliad massacres as they tried to surrender. The battle lasted only 18 minutes ending in a complete rout.

The Treaties of Velasco

The following day the Texans captured Santa Anna hiding in marsh disguised as a simple Mexican private. He was brought before General Houston who was resting under the shade of a large oak tree recovering from his wound. As news of Santa Anna’s capture spread throughout the Texan camp, many wanted to hang Santa Anna for his actions at the Alamo and Goliad. Houston was a strategic thinker and understood that Santa Anna was more valuable alive than dead. Two other Mexican armies under Generals Vicente Filisola and Jose Urrea were bearing down on Houston and his men and Santa Anna suggested that he order the remaining Mexican troops to pull back in return for sparing his life. He dispatched a letter to the commanders of the two armies acknowledging his capture and ordered the troops to retreat to San Antonio and await further instructions. Urrea wanted to ignore Santa Anna’s instructions and continue fighting the Texans. Filisola didn’t want to risk another disaster. His forces were experiencing ammunition shortfalls and his supply lines had broken down leaving little hope for resupply or reinforcements. Moreover, the spring rains had left many of the roads impassable.

Santa Anna spent the next several weeks and months in captivity, negotiating his release. He suggested two treaties, a public version of the promises made between the two countries, and a private version that included Santa Anna’s personal agreements. The Treaties of Velasco required that all Mexican troops withdraw south of the Rio Grande and that all private property be respected and restored. Prisoners of war would be released unharmed, and Santa Anna would be given immediate passage to Veracruz. He also secretly promised to persuade the Mexican Congress to acknowledge the Republic of Texas and to recognize the Rio Grande as the border between the two countries. On June 1, 1837, Santa Anna boarded a ship to travel back to Mexico. Three days later he arrived in Mexico and was placed under military arrest.

The Mexican authorities quickly denounced the agreements that Santa Anna negotiated, claiming that as a prisoner of war, he had no authority. They refused to recognize the Republic of Texas and there was a general feeling inside Mexico that the army would regroup and reconquer Texas. However, political instability in Mexico largely thwarted these hopes. Larger expeditions were postponed as military funding was repeatedly diverted to stifle other rebellions, out of fear that those regions would ally with Texas and tear the country apart further. Moreover, a large number of American volunteers flocked to the Texan army in the months after the victory at San Jacinto, further complicating Mexico’s ability to restore its authority over its rebellious province. As a result, Texas emerged as a de facto independent republic and functioned as a sovereign state until it was annexed by the United State on December 29, 1845.

A Republic if You Can Keep it

The newly minted Texas Republic quickly took shape but its nearly ten-year existence as a sovereign state would prove more challenging. In September, Houston was overwhelmingly elected President of the new Texas Republic after entering the race at the last minute. A new bicameral legislature was stood up the following month consisting of 14 senators and 29 representatives. Houston also appointed well-known Texans to his cabinet to help him deal with the problems of the new Republic. Stephen F. Austin served as secretary of state. Former provisional Governor Henry Smith was named secretary of the treasury. Thomas J. Rusk continued as secretary of war, a position he had held under Governor Smith during the ad interim government of Texas.

The challenges facing the new republic centered on three areas security, finances, and international recognition. The Mexican government refused to recognize Texas’ independence, so the two states were technically still at war. And while Mexico was consumed by political instability that greatly impaired its ability to reassert its control over Texas, the new Texan leadership needed to prepare as though a resumption of war was on the horizon. A tribe of Native Americans, the Comanches, posed an ever present danger, conducting raids on frontier settlements from San Antonio to northern Mexico. The Comanches were quiet during the revolution but now resented the growing number of settlers invading their territory and they threatened to declare war. Houston was cautious in his policies. He did his best to prevent another war with Mexico and instituted a policy toward the Comanches aimed at establishing peace and friendship through greater commerce.

On the financial front, the fledgling republic was deeply in debt. The provisional Texas government had incurred a debt of $1.25 million to win its independence from Mexico that needed to be repaid. Houston tried to hold government expenses to a minimum and began to raise revenues by collecting customs duties and property taxes, but the debt continued to rise. Houston’s successor as President, Mirabeau Lamar, completely mismanaged the republic’s finances, squandering money on an unnecessary war against the Comanches, purchasing ships to outfit a Texan navy, and other misguided policies only further enlarged the debt. By the time of annexation, the debt of the Texas Republic climbed to $12 million while the purchasing power of the Texas dollar shrunk to 15 cents.

Perhaps the most crucial question to address for the Texas leadership was the issue of international recognition and the possibility of annexation by the United States. Mexico refused to acknowledge Texan independence and the threat of renewed conflict constantly loomed over the nascent republic. The Texans desperately wanted international recognition of their new republic hoping that if other nations recognized that Texas was no longer part of Mexico, then Mexico would do the same. Most important was diplomatic recognition by the United States. In fact, most citizens of the new republic were overwhelming in favor of Texas being annexed by the United States.In September of 1836 an overwhelming majority of Texan voters endorsed a resolution to seek admission into the United States, viewing annexation as a solution to all their problems.

The question of Texas was a thorny issue in American politics in the 1830s and 1840s because it carried with it the potential of war with Mexico and it was deeply tangled up in the debate over slavery. The loss of Texas by way of the Adams-Onis Treaty had always infuriated President Andrew Jackson and he tried to purchase the territory from Mexico early in his presidency, offering a paltry $1 million. Moreover, he had personal relationships with key players in the Texas drama, including Texan President Sam Houston who was from Tennessee and was once Jackson’s protégé. Nonetheless, the President wanted neither war with Mexico nor domestic strife over adding what would likely become another slave state. With the 1836 U.S. presidential election looming, Jackson strived to avoid creating any controversy that would hand the election to the rival Whig Party. Jackson waited to the waning minutes of his presidency and on March 4, 1837 officially recognized the independence of Texas.

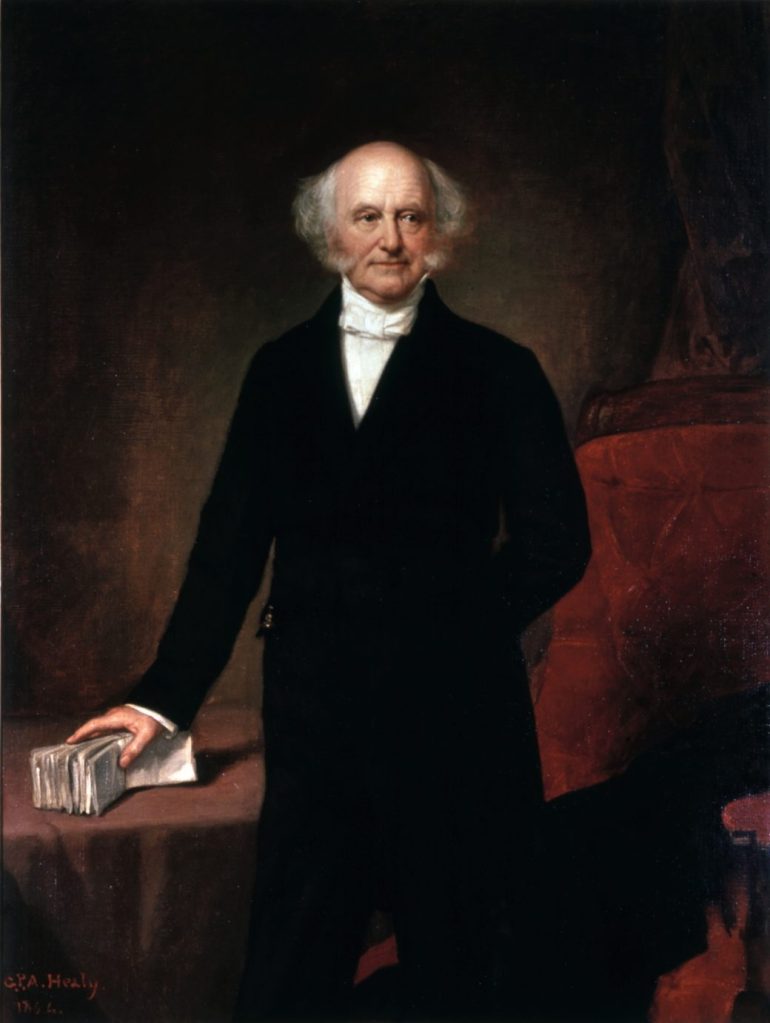

Jackson’s last minute recognition eased some of the tension and urgency surrounding the Texas question but it did little to satiate the annexation advocates. President Martin Van Buren, Jackson’s successor, was a New York Democrat, who did not share Jackson’s affinity and fixation with Texas. In fact, Van Buren viewed Texas more as a liability than a gift. He worried that it would empower the anti-slavery northern Whig opposition – especially if annexation provoked a war with Mexico. Moreover, only five weeks into his presidency, the United States was in the midst of a financial panic, one which would last way into the early 1840s. As a result, Van Buren had little interest in taking on Texas with its almost $10 million debt. Presented with a formal annexation proposal in August 1837, Van Buren declared he would not support the annexation of Texas.

Annexation and the Election of 1844

The push for annexation received a shot in the arm after John Tyler became president. Tyler was an accidental president. He was selected as William Henry Harrison’s running-mate in the 1840 presidential election on the Whig ticket. He became President only after Harrison died of pneumonia 30 days in to his term of office. Tyler, a Virginia slave holder, was not well liked inside the Whig party. He was selected largely as a compromise candidate and to siphon Southern support away from the Democrats. In fact other than sharing a disdain for former President Andrew Jackson, Tyler probably had more in common with the Democrats which frequently put him at odds with most of the party. In 1841, Tyler was expelled from the Whigs after vetoing two bills aimed at reestablishing a national bank and other priority legislation.

Rejected by the Whigs, Tyler viewed the annexation question as a political opportunity. Tyler did not worry that an outright annexation of Texas might spark a war with Mexico or fuel further sectional divides. On the contrary, he was quite prepared to put his own personal political ambitions ahead of the welfare of the country. Tyler wanted to exploit the annexation issue to boost his long shot hopes of a second term. His closest advisors counseled him that obtaining Texas would help him win a second term in the White House. He hoped to either steal the 1844 Democratic presidential nomination by aligning himself with southern Democrats who favored the expansion of slavery or by siphoning off pro-slavery voters in both parties who were so inclined. As a result, the acquisition of Texas became a personal obsession for Tyler and the “primary objective of his administration”..

Tyler made it abundantly clear that he had designs on Texas during his first address to Congress in 1841 by announcing his intention to pursue an expansionist agenda. In 1843, Tyler forced the resignation of his anti-annexation Secretary of State Daniel Webster, replacing him with Abel P. Upshur, a Virginia states’ rights champion and ardent proponent of Texas annexation. By late 1843, Upshur was in secret negotiation with Texas emissaries. These moves brought a swift rebuke from Mexico which made clear that any annexation would be regarded as an act of war. They were also roundly condemned by anti-slavery forces inside the United States. Former President, now Congressman, John Quincy Adams, led the resistance, warning that a conspiracy by slaveholders to expand the bounds of slavery was afoot.

In April 1844, U.S, negotiators and their Texan counterparts reached agreement to bring Texas into the United States. Under the terms of the agreement Texas would cede all its public lands to the United States, and the federal government would assume all its bonded debt, up to $10 million. The boundaries of the Texas territory were left unspecified. With the terms of annexation nailed down, all that was left was for the Senate to ratify the agreement. However, in early June, the Senate wrecked Tyler’s carefully orchestrated plan. On June 8, two-thirds of the Senate voted to reject the treaty (16-35). The Whigs opposed it almost unanimously (1-27) while the Democrats split with the majority in favor of the agreement (15-8). Defeated and dejected, Tyler dropped out of the presidential race in August but that was not the end of his Texas dream. Tyler, assured Democratic Party leaders, which were now unequivocally behind bringing Texas into the Union, that as president he would effect Texas annexation one way or another and he urged his supporters to vote Democratic.

The Texas question defined the Presidential campaign of 1844, despite the Senate’s earlier rejection of Tyler’s treaty. Initially the two front runners, Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky for the Whigs and former President Martin Van Buren for the Democrats, had reached a gentleman’s agreement not to discuss the issue of Texas during the campaign because of its volatility. However, Southern Democratic politicians, including former President Andrew Jackson, sought to use the Texas issue to deprive Van Buren of the nomination. Instead they sought to elect Tennessee Governor James K. Polk, a slaveholder who favored annexing Texas. In an election that was decided by about only 38,000 popular votes, Polk was elected the eleventh President of the United States.

Following Polk’s narrow victory, President Tyler declared that the people had spoken on the issue of annexation, and in he resubmitted the matter to Congress in a lame-duck session. This time he proposed that Congress adopt a joint resolution by which simple majorities in each house could secure ratification for the treaty. Involving the House of Representatives into the equation boded well for the treaty as the pro-annexation Democratic Party held a 2:1 majority in that chamber. On January 25, 1845, the House approved the treaty 120-98, in a vote that pretty much went along party lines. Little over a month later, the Senate followed suit and approved the treaty 27-25. All twenty-four Democrats voted for the measure, joined by three southern Whigs. On March 1, 1845, Tyler approved the joint resolution just three days before he left office. President Polk signed the Texas Admission Act into law on December 29, 1845, and Texas formally became the 28th state on February 19, 1846.

The March to War

The admission of Texas into the United States fundamentally resolved the Texas question once and for all. However, it did little to satiate the expansion-minded Polk administration or southern slaveholding elites who continued to eye additional Mexican territory for annexation and the extension of slavery.

Even though Texas was now part of the United States, disagreement over its southern border remained a bone of contention between Mexico and the US. The Polk administration would use this dispute as a pretext to go war with Mexico and to seize California, New Mexico and the rest of the territory that presently makes up the American southwest.

Texas claimed the Rio Grande as its southern border while Mexico argued the Nueces River, to the north, should be the border. In January 1846, President Polk ordered American General Zachary Taylor to establish a military camp beyond the Nueces River to provoke the Mexicans and buttress American claims. Three months later, Mexican military forces attacked Taylor’s army providing the casus beli Polk had sought. On May 13, Congress declared war on Mexico, despite opposition from some northern lawmakers, who saw the war as nothing more than a trumped up land grab to extend slavery.

The war would end in less than two years and when the dust cleared Polk had substantially increased the size of the United States winning control over territory that included nearly all of present-day California, Utah, Nevada, Arizona and New Mexico. Nevertheless, it was a deeply unpopular war. A war that future war hero and President of the United States, Ulysses S. Grant President called “one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation. The war was won but conflict over what to do with the vast amounts of territory gained from the war sparked further controversy in the U.S. The question over whether slavery would spread to these new territories would drive North and South even further apart inching the nation closer to civil war.