On June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, presumptive heir to the Hapsburg throne, was assassinated in the Bosnian capital of Sarajevo by a young Serbian nationalist, Gavrilo Princip in what would prove to be a key turning point in the history of the 20th century. The Archduke’s murder put in motion a series of events that would unleash the greatest calamity the world had known up to that point, World War I. The war would destroy an entire generation of European young men, 20 million dead soldiers and another 21 million wounded. It would not be what U.S. President Woodrow Wilson declared, “the war to end all wars.” It only laid the ground work for an even greater catastrophe twenty five years later, World War II.

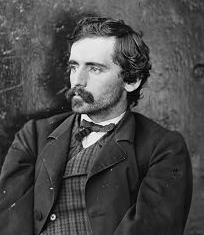

By the beginning of the 20th century, the Hapsburg empire had become an increasingly unruly multi-ethnic empire with various ethnic groups at odds with each other or agitating for independence. One such problematic group was the ethnic Serbs of Bosnia-Herzegovina, a multi-ethnic territory the Hapsburgs seized from the Ottoman Empire in 1874. Ethnic Serbs comprised about 40 percent of Bosnia’s population, many of who were intent on integrating Bosnia with Serbia to form a “Greater Serbia” state, a goal that Serbia encouraged and actively worked to realize. Serbian military intelligence, with or without the consent of the Serbian government, was actively engaged in covert actions to undermine Vienna’s control over the province. One such operative was Colonlel Dragutin Dimitrijević, the leader of a secret Serbian military society, called “the Black Hand” whose aim was to unite all of the South Slavs of the Balkans under Serbian rule. Dimitrijevic, or Apis, as he was better known, was cultivating ties with a group of radical Serbian separatists called the “Young Bosnia” movement that would play a pivotal role in the events leading up to World War I.

The Archduke was not only Emperor Franz Joseph’s presumptive heir; he was also inspector general of the Austrian-Hungarian army. And in that capacity, he agreed to attend a series of June 1914 military exercises in Bosnia. Franz Ferdinand was dismissive of the Serbs, often referring to them as “pigs,” “thieves,” “murderers” and “scoundrels.” Nevertheless he was also quite sensitive, perhaps more than any other high level official, to the ethnic powder keg that the multi-ethnic Hapsburg Empire had become as it expanded. The Archduke supported reforming the empire from the dual Austro-Hungarian monarchy to a a triple monarchy of Slavs, Germans and Hungarians each having an equal voice in government. This idea was unpopular with the Hapsburg ruling elite but Franz Ferdinand saw it as a more effective way of neutralizing the problem of the Serbs than military force that risked a larger war with Russia, Serbia’s ally.

The date selected for Franz Ferdinand’s visit, June 28, unfortunately coincided with another important event in Serbian history. It was the anniversary of the 1389 Battle of Kosovo Polje in which the Serbs were defeated by the Ottoman Turks and subjugated under Turkish rule for the next 500 years. The battle, in which both Serbian King Lazar and the Ottoman Sultan Murad were killed, plays a crucial role in Serbian national identity and the decision to hold the Archduke’s visit on that day only fanned the flames of dissent among Serbian nationalists even further.

News of Franz Ferdinand’s upcoming visit to Sarajevo prompted Serbian radicals associated with the Young Bosnia movement to begin plotting to assassinate him. On the morning of the Archduke’s visit, seven Bosnian Serbs, armed with pistols, bombs, and cyanide capsules likely provided by Serbian military intelligence, fanned out along the expected motorcade route as he and his entourage drove through the city to City Hall. As the motorcade approached the first two assassins, they lost their nerve and failed to act. A third assassin, Nedeljko Cabrinovic, was not so reticent. Shortly after 10:00am, Cabrinovic tossed a bomb at the open roof sedan carrying the Archduke and his wife. The bomb bounced off their car exploding underneath the one directly behind it injuring the occupants. The Royal couple arrived safely at City Hall for their scheduled reception with no further attempts on their lives.

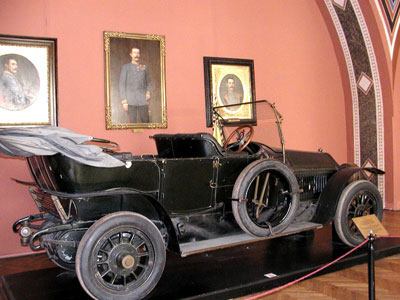

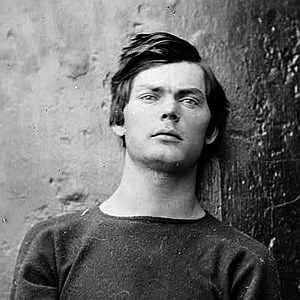

After finishing up their reception at City Hall, Franz Ferdinand made the fateful decision that he wanted to go to the hospital and visit those who had been injured in the failed assassination attempt. This change in plans would end in tragedy. The driver, unfamiliar with the local streets accidentally turned down a wrong side street, just where another assassin, Gavrilo Princip, happened to be standing by chance. As the Archduke’s driver attempted to reverse back onto the main road, Princip pulled out his pistol and fired two shots at the archduke from point-blank range, piercing him in the neck and also striking his wife in the abdomen. Both would die within minutes of their wounds.

Austria-Hungary was convinced that neighboring Serbia was the true mastermind behind the attack and opted to use the crisis to settle its long-standing score with the Serbs. The Austrians hoped to strike a blow against Belgrade and stymie its efforts to unite the South Slavs of the Balkans under Serbian leadership. Their plan, developed in coordination with Germany, was to force a military conflict that would, they hoped, end quickly and decisively with a crushing Austrian victory before the rest of Europe—namely, Serbia’s powerful ally, Russia—had time to react.

On July 23, the Austro-Hungarian government issued Serbia an ultimatum in which it blamed Serbia for the assassination and presented Belgrade with a list of demands that it expected to be fulfilled by Belgrade or it would declare war. The Serbs were given two days to respond. The list consisted of ten demands, many of which the Austrian leadership believed Serbia would never agree to accept. Winston Churchill, at the time in charge of Britain’s Royal Navy, called the Austrian ultimatum “the most insolent document of its kind ever devised”. In short, the ultimatum was intended as a pretext to justify war. Much to the surprise of the Austrians, Serbia agreed to almost all of the demands, only refusing to accept a direct investigation by Austro-Hungarian police officers on its territory. Serbia continued to insist that it gave no moral or material support to Princip and the other assassins.

Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia on July 28, 1914, exactly a month after the assassination of the Archduke. The declaration set off a chain of events that would plunge the entire continent into crisis. Russia, Serbia’s long-time protector, condemned Austria’s aggression and on July 30 began mobilizing its military forces in support of its ally. Germany followed suit as expected and on August 1, declared war on Russia. At the same time Berlin demanded a declaration of neutrality from France to avoid a two-front war. When Paris refused, Germany felt it had no alternative and declared war on France on August 3. The next day Germany invaded Belgium to attack France. Great Britain, which had pledged to defend Belgium demanded an explanation for German aggression against Belgium. When one was not forthcoming Britain declared war on Germany. The war that all the European powers had long expected finally erupted.