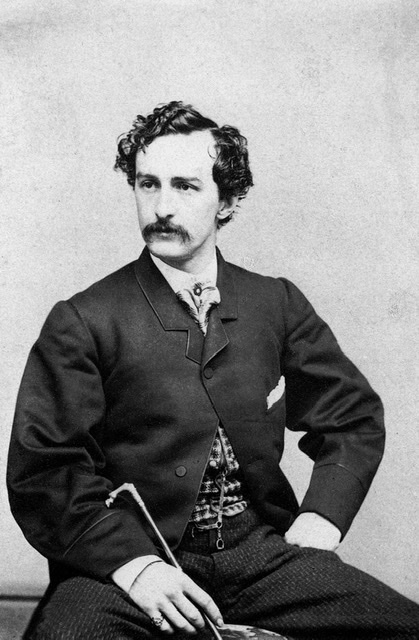

On April 14, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth at Ford’s Theater in Washington DC while attending the play, “Our American Cousin.” Booth, a popular actor at the theater and southern sympathizer, had free access to all areas of the theater. Around 10 pm, He quietly slipped into the box where Lincoln and his wife were sitting and fired his single shot Derringer pistol into the back of the head of the President at point blank range with deadly effect. Booth quickly leaped from the box onto the stage, where he shouted “Sic semper tyrannis,” (Thus always to Tyrants) before bowing and fleeing into the night. Lincoln’s body was brought to a house across the street from the theater, where he would succumb to his wound around 7:30 am the following day. Lincoln’s assassination would forever alter the course of history, thrusting the woefully inept Vice President Andrew Johnson into the presidency. Johnson would prove ill-tempered and ill-suited for the challenge of putting the country back together after four years of civil war.

Portrait of an Assassin

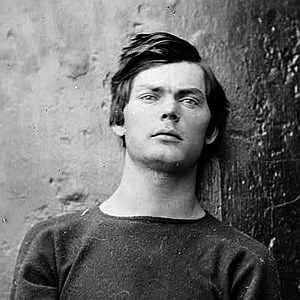

Booth was born into a well known family of Maryland thespians in 1838. His father, Junius Brutus Booth, was a widely regarded British Shakespearean actor who immigrated to the United States with his mistress, Booth’s mother, in 1821 and is considered by many, the greatest tragic actor in the first half of the 19th century. His older brother Edwin followed in his father’s footsteps and was judged by many to be the greatest American Shakespearean actor of the 19th century. Thus it was not surprising that John Wilkes Booth would be drawn to the theater. He made his stage debut at the age of 17 in a production of Richard III by Baltimore’s Charles Street Theater. Although his initial performance was underwhelming he soon joined a Shakespeare production company in Richmond, Virginia where he earned rave reviews for his acting talents. Some critics called Booth “the handsomest man in America” and a “natural genius.”

Nevertheless, like many Maryland families, the Booths were politically divided. Junius and Edwin were staunch Unionist while the younger Booth harbored strong southern sympathies. He supported the institution of slavery and despised abolitionists. After the 1860 election and the beginning of the Civil War he would develop an intense hatred for Lincoln. There has been much speculation that John Wilkes Booth’s embrace of the southern cause was part of a larger sibling rivalry with his older brother Edwin and to step outside the shadow of his famous father. In 1860, Booth joined a national touring company performing in all the major cities north and south, where he soon began to equal if not surpass his more famous brother in terms of popularity and acclaim. One Philadelphia drama critic remarked, “Without having [his brother] Edwin’s culture and grace, Mr. Booth has far more action, more life, and, we are inclined to think, more natural genius.” He was also becoming quite a wealthy actor, earning $20,000 a year (equivalent to about $569,000).

With the outbreak of the Civil War in April 1861, Booth found it increasingly more difficult to conceal his Southern sympathies or his hatred for Lincoln. Booth, like most southerners abhorred Lincoln. He saw him as a “sectional candidate” of the North and a tool of the abolitionists to crush slavery. Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus and the imposition of martial law in Maryland in May 1861, outraged Booth. He saw these actions as evidence of Lincoln’s treacherous and duplicitous nature and his intent to overturn the republic and make himself king. Booth increasingly quarreled with his brother Edwin, who declined to make stage appearances in the South and refused to listen to his brother’s fiercely partisan denunciations of the North and Lincoln. In early 1863, Booth was arrested in St. Louis while on a theatre tour, when he was heard saying that he “wished the President and the whole damned government would go to hell.” He was charged with making “treasonous” remarks against the government, but was released when he took an oath of allegiance to the Union and paid a substantial fine.

In November of 1863, A family friend John T. Ford opened 1,500-seat Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C. Booth was one of the first leading men to appear there while Lincoln became one of the theater’s more prominent patrons. In his first role, Booth played a Greek sculptor making marble statues came to life. One evening when Lincoln was watching the play from his box, Booth was said to have shaken his finger in Lincoln’s direction as he delivered a line of dialogue. Lincoln’s sister-in-law, who was sitting with him turned to him and said, “Mr. Lincoln, he looks as if he meant that for you.”The President replied, “He does look pretty sharp at me, doesn’t he?” An admirer of Booth’s acting talents, Lincoln would invite Booth to visit the White House several times but Booth demurred.

A Turn for the Worse

By 1864 the Confederacy’s hopes for victory were diminishing rapidly which only served to intensify Booth’s hatred of Lincoln whom he blamed for he war. After the battle of Gettysburg the previous summer, the Confederacy was hemorrhaging manpower with fewer and fewer options to replace its diminishing ranks. The situation became particularly acute after General Ulysses S. Grant, commander of the Union armies, suspended the exchange of prisoners of war with the Confederate Army to increase pressure on the manpower-starved South. It became absolutely dire following the terrible Confederate loses at the battles of the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Cold Harbor in the Spring of 1864. As the hopes of the Confederacy ebbed, Booth became increasingly distraught. Booth had promised his mother at the outbreak of war that he would not enlist as a soldier, but he increasingly chafed at not fighting for the South, writing in a letter to her, “I have begun to deem myself a coward and to despise my own existence.”

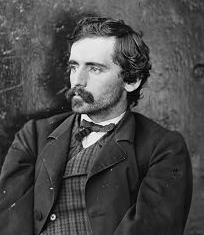

To assuage his own guilt and to reverse the declining fortunes of the Southern Confederacy, Booth began to conceive of a plan to kidnap Lincoln and take him to Richmond, believing he could ransom the President back to the Federal Government to free Southern troops. Lincoln’s re-election in November 1864 only further infuriated Booth and created an additional sense of urgency. Booth began to assemble a team of co-conspirators, a mix of Southern sympathizers and likely Confederate agents, who would assist him with the deed.

After Lincoln’s inauguration on March 4, 1865, Booth learned that the President would be attending the play Still Waters Run Deep at the Campbell Hospital on March 17 and considered it a perfect opportunity to kidnap Lincoln. His plan was to intercept the president’s carriage on his way to the play. Booth’s plan this day was spoiled by Lincoln’s change of plan. Instead he decided to speak to the 140th Indiana Regiment.

Murder Most Foul

With his initial plans thwarted, Booth and his conspirators went back to the drawing board. However, the fall of Richmond on April 2nd and Lee’s surrender a week later at Appomattox made Booth’s kidnapping plot impractical and irrelevant. The collapse of the Confederacy filled Booth with despair but a speech Lincoln would give would drive Booth in a more deadly direction. On April 11, two days after Lee’s surrender, Lincoln addressed a large assembly of people outside the White House. Among those in the group were Booth and his accomplices David Herold and Lewis Powell. Lincoln’s speech focused largely on healing and putting the fractured nation back together. During his speech, Lincoln called for limited Negro suffrage—giving the right to vote to those who had served in the military during the war, for example. Hearing those words, Booth muttered to companions, “That means nigger citizenship. That is the last speech he will ever make.” He tried to convince one of those companions to shoot the president then and there.

By this time an angry Booth was completely fixated on assassinating Lincoln. He told a friend that he was done with the stage. and that the only play he wanted to present henceforth was Venice Presseved, a play about an assassination. On the morning of Good Friday, April 14, 1865, Booth went to Ford’s Theater to get his mail. While there, he was told by The owner’s brother that the President and Mrs. Lincoln would be attending the play, Our American Cousin that evening, accompanied by Gen. and Mrs. Ulysses S. Grant. He immediately set about making plans for the assassination, which included making arrangements with the livery stable owner for a getaway horse and an escape route. Later that night, at 8:45 pm, Booth informed Powell, Herold, and Atzerodt of his intention to kill Lincoln. He assigned Powell to assassinate Secretary of State William Seward and Atzerodt to do the same to Vice President Andrew Johnson. Herold would assist in their escape into Virginia.

Booth entered Ford’s Theater one last time at 10:10 pm. In the theater, he slipped into Lincoln’s box at around 10:14 p.m. as the play progressed and shot the President in the back of the head with a .41 caliber Deringer pistol. Booth’s escape was almost thwarted by Major Henry Rathbone who was in the presidential box with Mary Todd Lincoln and his fiancée Clara Harris. Rathbone and Harris were guests of Mrs. Lincoln and last minute replacements for General Grant and his wife who opted to visit family in New Jersey instead. Booth stabbed Rathbone when the startled officer lunged at him before jumping from the box onto the stage. Rathbone would suffer from serious mental issues the rest of his life because of his failure to stop Booth.

Booth was the only one of the assassins to succeed. Posing as a pharmacy delivery man, Powell entered Seward’s home where he forced his way upstairs, stabbing the Secretary of State,who was bedridden as a result of an earlier carriage accident, before being subdued. Although Seward was seriously wounded, he would survive. Atzerodt lost his nerve and spent the evening drinking alcohol, never making an attempt to kill Johnson.

Manhunt

After jumping onto the stage, Booth fled by a stage door into an alley, where his getaway horse was waiting for him. He and David Herold rode off into southern Maryland, planning to take advantage of the sparsely settled area’s lack of telegraphs and railroads, along with its predominantly Confederate sympathies. He thought that the area’s dense forests and the swampy terrain made it ideal for an escape route before crossing the Potomac River back into rural Virginia.

Federal troops combed the rural area’s woods and swamps for Booth in the days following the assassination. The hunt for the conspirators quickly became the largest in U.S. history, involving thousands of federal troops and countless civilians. Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton, personally directed the operation.

On April 26, soldiers of the 16th New York Cavalry tracked Booth and Herold to a farm in Virginia, just south of the Rappahannock River, where they were sleeping in a barn. The soldiers surrounded the barn and threatened to light it on fire if they did not come out and surrender. Herold surrendered, but Booth cried out, “I will not be taken alive!” The soldiers set fire to the barn and Booth scrambled for the back door with a rifle and pistol.

Sergeant Boston Corbett shot Booth in the back of his head, severing his spinal chord. Paralyzed, the soldiers carried Booth to the steps of the barn. As he lay dying, he told his captors to tell his mother that he died for his country. Two hours later he was dead. By the end of the month, all of Booth’s co-conspirators were arrested except for John Surrat who fled to Canada and would be arrested a year later in Egypt.

After a seven week long military tribunal, four of Booth’s co-conspirators, Herold, Powell, Azterodt and Mary Surrat (John Surrat’s mother) were convicted and sentenced to death by hanging. Surrat would become the first woman executed by the Federal Government. Dr. Samuel Mudd, Samuel Arnold, and Michael O’Laughlen were sentenced to life in prison while Edmund Spangler was sentenced to six years. O’Laughlen died in prison in 1867 but Mudd, Arnold, and Spangler were pardoned in February 1869 by Johnson.

News of Linoln’s death was met with an outpouring of grief across the country. On April 18, Lincoln’s body was carried to the Capitol rotunda to lay in state on a catafalque. Three days later, his remains were boarded onto a train that conveyed him to Springfield, Illinois where he had lived before becoming president. Tens of thousands of Americans lined the railroad route and paid their respects to their fallen leader during the train’s solemn progression through the North. Frederick Douglass called the assassination an “unspeakable calamity” while General Ulysses S. Grant, called Lincoln “incontestably the greatest man I ever knew.” In the South Lincoln’s assassination was met with both joy and trepidation. Some believed Lincoln got what he deserved and saw Booth as a hero. South Carolina diarist Emma Le Conte wrote,”Hurrah! Old Abe Lincoln has been assassinated! It may be abstractly wrong to be so jubilant, but I just can’t help it. After all the heaviness and gloom… This blow to our enemies comes like a gleam of light.” Still others worried that all Southerners would be implicated, complicating efforts to heal the nation and put the divided country back together.