On the afternoon of July 3, 1863, 12,000 Confederate troops carried out a vain and desperate assault on the Union front along Cemetery Ridge seeking to break the Federal line and steal a victory from the jaws of defeat. The attack, which would cross over a mile of open field and come under a withering storm of artillery was easily repelled. The following day General Robert E. Lee gathered his forces and casualties and began the long retreat across the Potomac, back into Virginia. The second Confederate invasion of the North had again ended in failure.

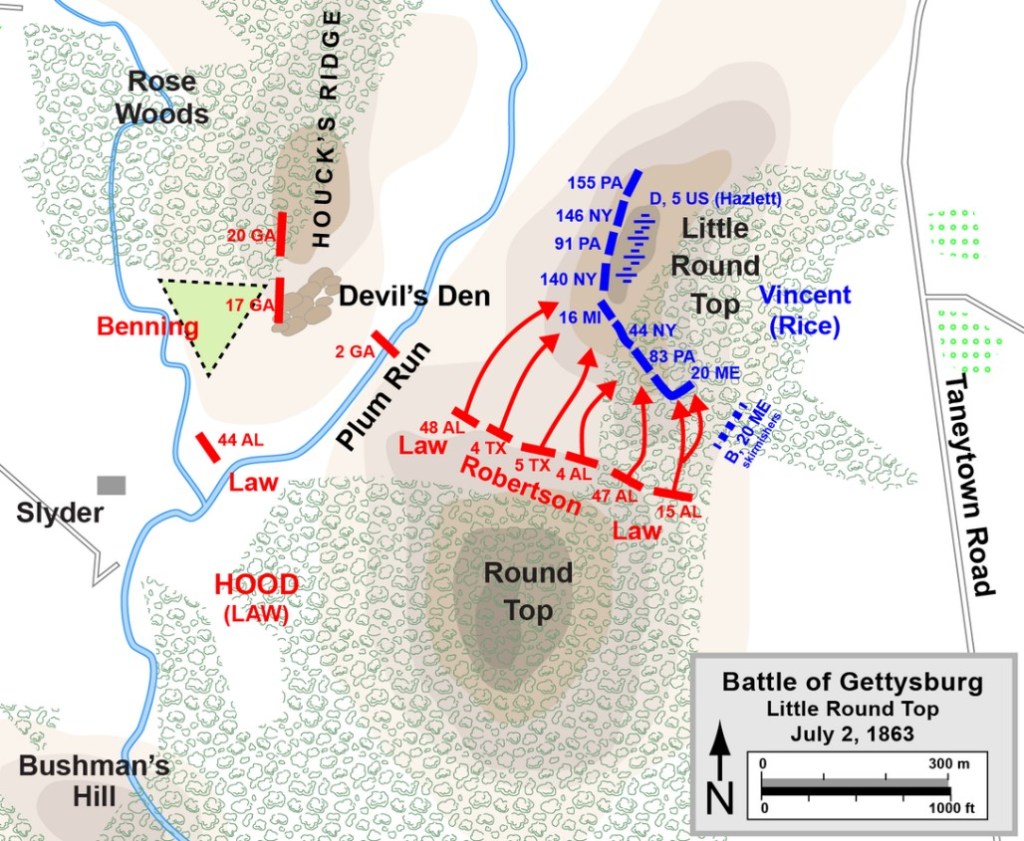

The second day of the battle of Gettysburg proved as disastrous for the Confederacy as the first day was fortuitous. Every Confederate attack up and down the Emmitsburg Pike was beaten back. The rebels had their opportunities. They had broken the Union lines in spots but strong interior lines and and a reserve of reinforcements allowed the Federals to quickly plug any holes and push the rebels back.

Despite the failures of the previous day, General Robert E. Lee was committed to continuing the battle the following day. Longstreet continued to argue against any offensive operations but his objections fell on deaf ears. Having attacked the left and right of the Union line with little success, Lee reasoned that the Union center must now be weakened. He incorrectly assumed that the Union Army commander, General George Meade, must have pulled reinforcements from the center to blunt the Confederate attacks on he flanks. Moreover, the last of his army, General George Pickett’s division of Virginians had finally arrived.

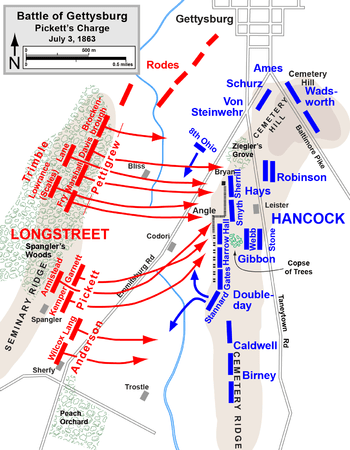

Lee’s plan of attack was simple. He would soften up the Union center with an artillery barrage, then, Pickett’s division, augmented by select regiments from Henry Heth and Isaac Trimble’s divisions that bore the brunt of the fighting on the first day, would advance across a mile of open field and strike the Union center. Although the plan was simple, execution was anything but.

The plan began to go awry from the get go. Around 1pm, 150 Confederate artillery pieces in a 2-mile long line along Seminary Ridge opened fire on the Union Center. Their orders were to silence as many Union batteries as possible on the north end of Cemetery Ridge before the infantry advanced. However, the barrage did not inflict the damage on the Union guns that the Confederate leadership had hoped. The immense amount of smoke generated by the cannonade hindered the aim of the Confederate gunners while inferior shell fuses ensured that some Confederate shells failed to detonate properly rendering them ineffective and leaving many Union batteries relatively unscathed.

As Confederate artillery began to run low on ammunition the infantry was ordered to form up and prepare for their advance. Around 3pm, Confederate troops stepped out from the tree line along Seminary Ridge and began to move forward in a mile long front proudly and in good order. Crossing over the Emmitsburg Pike, the rebels soon came under a withering fire from Union artillery. Federal guns atop Little Round Top ripped huge gaping holes in the Confederate right flank while those on Cemetery Hill did the same to the rebel left. Once on the other side of the pike, the attack began to falter as Union gunners along Cemetery Ridge switched to canister shot and musket fire became increasingly accurate and effective. Despite mounting losses the Confederates pressed on until they reached a small stone wall which was their destination. The remaining men rushed the stone wall and brutal hand-to-hand combat ensued. The Union quickly reinforced their lines with fresh men and counterattacked. The rebels, expecting reinforcements that never showed, were forced to flee back to their original lines. As the survivors straggled back to Seminary Ridge, many of them passed Robert E. Lee, who told them, “It is my fault.” The attack failed and with it any hope of victory.

In the words of William Faulkner, “For every Southern boy fourteen years old, not once but whenever he wants it, there is the instant when it’s still not yet two o’clock on that July afternoon in 1863, the brigades are in position behind the rail fence, the guns are laid and ready in the woods and the furled flags are already loosened to break out and Pickett himself with his long oiled ringlets and his hat in one hand probably and his sword in the other looking up the hill waiting for Longstreet to give the word and it’s all in the balance, it hasn’t happened yet, it hasn’t even begun yet, it not only hasn’t begun yet but there is still time for it not to begin against that position and those circumstances…

The Southern rebellion is now doomed. It is just now a matter of time.