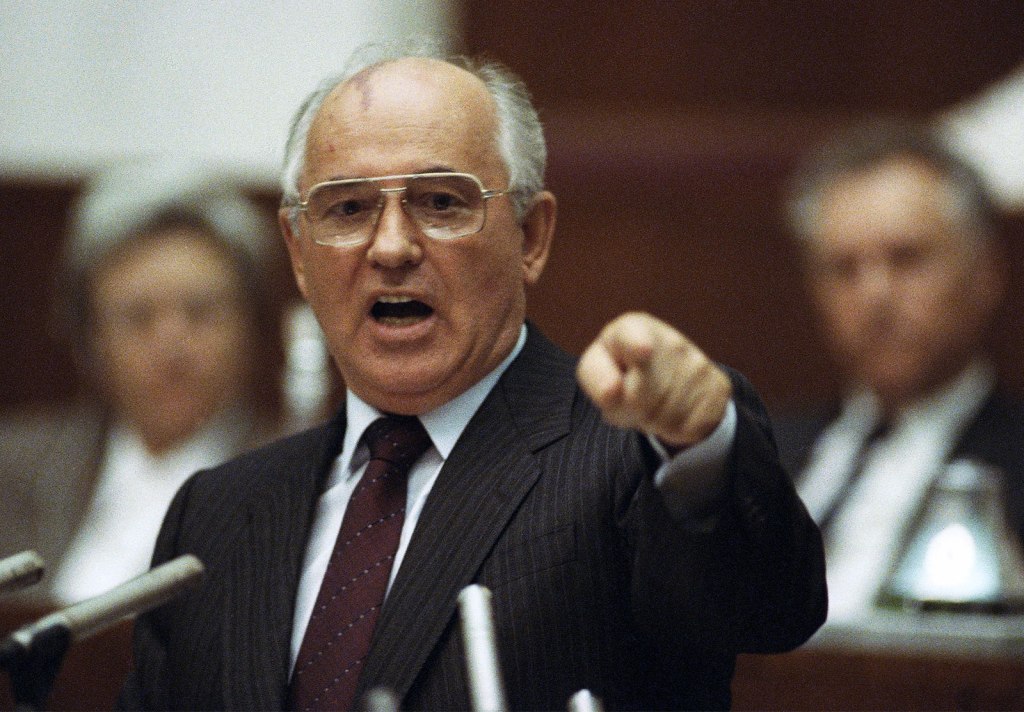

The attempted overthrow of Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev on August 19, 1991 by a group of hardliners was the tragic culmination of five very tumultuous years in which Gorbachev attempted to reform and reinvigorate the Soviet political-economic system but in doing so unleashed centrifugal forces that accelerated its demise. Gorbachev’s dilemma was the same one that confronted every modernizing Russian leader since at least Peter the Great, how to conduct effective reform of the system without jeopardizing or relinquishing political control. He was thrust into power with the expectation that he, unlike his geriatric predecessors, would be the young vibrant tonic needed to revive the Soviet system, the one to humanize it and make it more competitive with the West, not to preside over its whole-sale destruction and the collapse of the Soviet state. Gorbachev evolved from a measured reformer to a radical deconstructionist and back to a conservative reactionary having lost control of the reform process which soon became bigger than him. Gorbachev’s trademark slogans, Glasnost and Perestroika (openness and restructure), that inspired so much hope for meaningful reforms in the beginning of his rule quickly became insufficient in the face of demands for something more than tinkering at the edges. In the end, Gorbachev tried to put the genie back in the bottle, but it was too late.

Gorbachev instinctively understood that any successful reform effort would need to overcome an entrenched state and Communist Party bureaucracy resistant to change. He would also need a relaxation in tensions with the United States to focus on domestic challenges, break with the policies of the past that were bankrupting the state and to undercut the arguments of his opponents that reform would leave the USSR vulnerable to the United States.

Like any new leader, Gorbachev’s first task was to consolidate his power. Within a month of taking power he set about overhauling state and party cadres removing ossified plutocrats and replacing them with a younger generation of party leaders who shared his reform impulses. Gorbachev ousted two of his main rivals in the Politburo, Victor Grishin and Grigoriy Romanov, promoting close peers in their place. He replaced long standing Soviet Foreign Minister, Andrei Gromyko, with the relatively unknown First Secretary of the Georgian Communist Party Eduard Shevardnadze. He also rounded out his foreign policy team by promoting a close confidant, Aleksandr Yakovlev to be a foreign a foreign policy advisor and full member of the politburo. Yakovlev would be a key architect of Gorbachev’s “new thinking” in foreign policy.

Nonetheless, personnel changes alone were not going to overcome the bureaucracy. Gorbachev needed to create new institutions and expand civil society to gain greater control over the party apparatus. In doing so he created alternative centers of power and unleashed a wave of pent up nationalist sentiment in the non-Russian Republics of the Soviet Union that subverted Party authority and led to the fragmentation of the country. Gorbachev essentially created created Boris Yeltsin and at each part of the drama gave him a soap box to challenge the central government. In the non-Russian republics of the USSR, Gorbachev supported the creation of popular fronts as a way for people to mobilize society in support of his agenda. The Sajudis movement in Lithuania, Rukh in Ukraine, the Karabakh Committee in Armenia, and Birlik in Uzbekistan and others all started as vehicles in support of Gorbachev’s reforms. Eventually, these popular fronts assumed a more nationalistic character and began to agitate for greater political rights and independence from Moscow. So much so that the last two years of Gorbachev’s rule were dominated by the nationalities problem and the proximate cause underlying the coup attempt. The coup attempt was to prevent the signing of a new union treaty that Gorbachev had conceded to that would have devolved more power to the republics. It’s ironic that in attempting to stave off what the coup plotters saw as the dismantlement of the USSR, accelerated its collapse.