On August 9, 1974, President Richard M. Nixon departed departed the White House for the last time, bringing to an end the two year long national nightmare known as the Watergate Scandal. Facing certain impeachment and removal from office, Nixon resigned the prior evening in a prime time television broadcast to avoid the humiliation. Driven by Nixon’s paranoia and insecurity, it was a scandal that would rope in presidential aides at the highest level and eventually be traced back to the President himself. Fundamental principles of American Democracy, such as the rule of law, would come under fire from a President determined to evade responsibility for any criminal wrongdoing. The Watergate Scandal would forever change the course of American politics shattering the American public’s trust and confidence in its leaders and institutions.

In the Beginning…

Late in the evening on June 17, 1972, five men were arrested at the National Democratic Headquarters in the Watergate Hotel in Washington DC in what appeared to be a routine burglary at first glance. Follow on investigations revealed that these men—identified as Virgilio Gonzalez, Bernard Barker, James McCord, Eugenio Martinez, and Frank Sturgis— were not your ordinary run of the mill petty criminals but operatives working for the Committee for the Re-election of President Richard Nixon. They had been caught wiretapping phones and stealing documents as part of a larger campaign of illegal activities developed by Nixon aide G. Gordon Liddy to ensure Nixon’s re-election. On September 15, 1972, a grand jury indicted the five office burglars, as well as Liddy and another Nixon aide E. Howard Hunt for conspiracy, burglary, and violation of federal wiretapping laws. President Nixon denied any association with the break-in and most voters believed him, winning re-election in a landslide. At the urging of Nixon’s aides, five pleaded guilty to avoid trial; the other two were convicted in January 1973.

Nixon’s passionate denials aside, there was a pervasive sense, as well as evidence, that there was more to this story than simply five low level campaign workers acting independently in criminal activities against their political rivals. There were unanswered questions and numerous threats that all pointed to a darker conspiracy and greater White House involvement. On February 7, 1973, the United States Senate voted unanimously to create a Senate select committee to investigate the 1972 Presidential Election and potential wrongdoings. The committee which consisted of four Democratic and three Republican Senators, was empowered to investigate the break-in and any subsequent cover-up of criminal activity, as well as “all other illegal, improper, or unethical conduct occurring during the Presidential campaign of 1972, including political espionage and campaign finance practices.” Committee hearings were broadcast live on television in May 1973 and quickly became “must see TV” for an inquiring and curious nation. Although Nixon repeatedly declared that he knew nothing about the Watergate burglary, former White House counsel John Dean III testified that the president had approved plans to cover up White House connections to the break-in. Another former aide, Alexander Butterfield, revealed that the president maintained a voice-activated tape recorder system in various rooms in the White House which potentially contained information implicating the President in a criminal conspiracy. Only one month after the hearings began, 67 percent believed that President Nixon had participated in the Watergate cover-up.

The Saturday Night Massacre

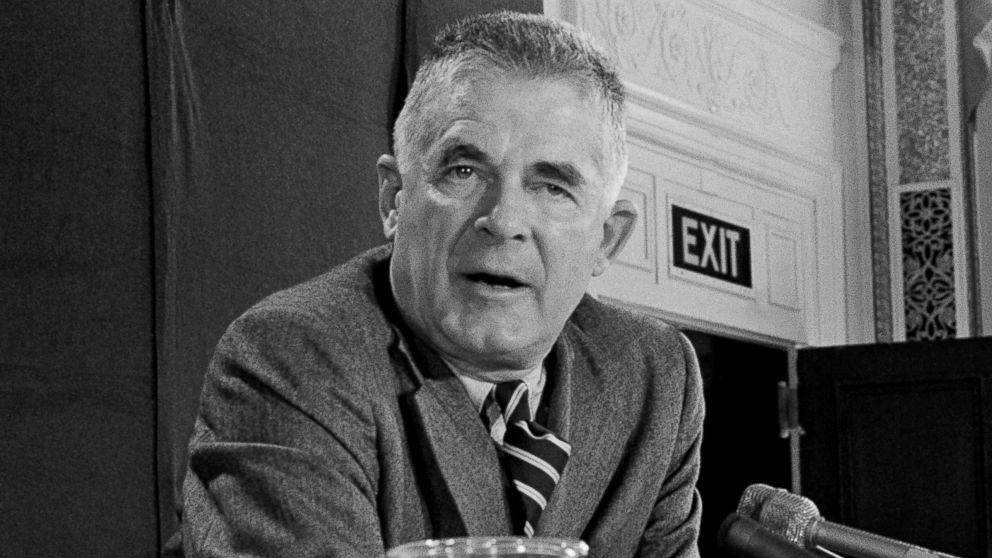

The revelation that there were recordings of potentially damaging information implicating Nixon and his efforts to prevent their disclosure soon became the central drama of the story. Nixon struggled to protect the tapes during the summer and fall of 1973. His lawyers argued that the president’s executive privilege allowed him to keep the tapes to himself, but the Senate committee and an independent special prosecutor named Archibald Cox were all determined to obtain them. On October 20, 1973, after Cox refused to drop the subpoena, Nixon ordered Attorney General Elliot Richardson to fire the special prosecutor. Richardson resigned in protest rather than carry out what he judged to be an unethical and unlawful order. Nixon then ordered Deputy Attorney General William Ruckleshaus to fire Cox, but Ruckelshaus also resigned rather than fire him. Nixon’s search for someone in the Justice Department willing to fire Cox ended with the Solicitor General, Robert Bork. Though Bork said he believed Nixon’s order was valid and appropriate, he considered resigning to avoid being “perceived as a man who did the President’s bidding to save my job”. This chain of events would go down in history as the “Saturday Night Massacre” and further turn the American public against Nixon. Responding to the allegations that he was obstructing justice, Nixon famously replied, “I am not a crook.”

Things went from bad to worse for the White House in the new year. On February 6, 1974, the House of Representatives began to investigate the possible impeachment of the President. Less than a month later, on March 1, 1974, a grand jury indicted several former aides of Nixon, who became known as the “Watergate Seven”—H.R. Haldeman, John Ehrlichman, John N. Mitchell, Charles Colson, Gordan C. Strachan, Robert Maridan and Kenneth Parkinson for conspiring to hinder the Watergate investigation. The grand jury secretly named Nixon as an unindicted co-conspirator. However the special prosecutor dissuaded them from an indictment of Nixon, arguing that a president can be indicted only after he leaves office, creating a precedent that lasts even today.

No Way Out

Nixon eventually released select tapes in an effort to tamp down growing public criticisms and perceptions that he was hiding something. The President announced the release of the transcripts in a speech to the nation on April 29, 1974 but noted that any audio pertinent to national security information could be redacted from the released tapes. This caveat almost immediately fueled suspicions that the White House was indeed hiding something more damning. The issue of the recordings and whether the White House was obligated to comply with the Congressional subpoena tapes went to the United States Supreme Court. On July 24, 1974, in United States v. Nixon, the Court ruled unanimously that claims of executive privilege over the tapes were void. The Court ordered the President to release the tapes to the special prosecutor. On July 30, 1974, Nixon complied with the order and released the subpoenaed tapes to the public.

Nixon’s fate was largely sealed on August 5, 1974 when the White House released a previously unknown audio tape that would prove to be a “smoking gun” providing undeniable evidence of his complicity in the Watergate crimes. The recording from June 23, 1972, less than a week after the break-in, revealed a President engaged in in-depth conversations with his aides during which they discussed how to stop the FBI from continuing its investigation of the break-in. Two days later, a group of senior Republican leaders from the Senate and the House of Representatives met with Nixon and presented him with an ultimatum, resign or be impeached.

On August 8, in a nationally televised address, Nixon officially resigned from the Presidency in shame. The following day he and his family departed the White House one last time, boarded Marine One and flew to Andrews Air Force base where they were shuttled back to their home in California. Vice President Gerald Ford was sworn in as President shortly thereafter. He would issue a full and unconditional pardon of Nixon on September 8 immunizing him from prosecution for any crimes he had “committed or may have committed or taken part in” as president.