It’s the summer of 1864 and the fortunes of the Confederacy are on the wane. The Army of Northern Virginia is suffering from shortages across the board but one shortage is especially problematic, manpower. The Army of Northern Virginia is steadily being attritted. A series of bloody battles beginning in early May have sapped the Army and put it on the defensive. In early May, at the battle of the Wilderness, Confederate losses number over 11,000. A week later at Spotsylvania Courthouse, the South suffers another 10,000 casualties. In early June, the Confederates return the favor at Cold Harbor inflicting over 10,000 Union losses but they also suffer another 4,500 losses. In little over a month, General Lee has lost a quarter of his army. Lee knows he cannot continue losing men at this pace but he has few options. Lee writes to his son, “Where do we get sufficient troops to oppose Grant? He is bringing to him now the Nineteenth Corps, and will bring every man he can get.” Unlike his predecessors, General Grant is a fighter. He knows that he has Lee on the ropes and he won’t let up. Grant continues to push towards Richmond forcing Lee to move his army to stay between Grant and the rebel capital. Grant deprives Lee of the initiative and Lee is now forced to fight a defensive campaign against Grant’s numerically superior army, one that is not Lee’s strong suit.

Unable to get between Lee and Richmond, Grant turns his eye toward the critical rail junction of Petersburg, thirty miles south of the capital. Petersburg is vital to the supply of Richmond and its loss would make Richmond’s capture almost inevitable. Shortly after Cold Harbor, Grant marches his forces towards Petersburg and Lee races southward toward Petersburg knowing what its loss would mean. By June 18, Grant had nearly 100,000 men under him at Petersburg compared to the roughly 20,000-30,000 Confederate defenders. Grant realized the fortifications erected around the city would be difficult to attack and pivoted to starving out the entrenched Confederates. Grant had learned a hard lesson at Cold Harbor about attacking Lee in a fortified position but is chafing at the inactivity to which Lee’s trenches and forts had confined him. A regiment of Pennsylvania miners offered a proposal to break the impasse. They would dig a long mine shaft under the Confederate lines and detonate explosives directly underneath fortifications in the middle of the Confederate First Corps line. If successful, not only would all the defenders in the area be killed, but also a hole in the Confederate defenses would be opened. If enough Union troops filled the breach quickly enough and drove into the Confederate rear area, the Confederates would not be able to muster enough force to drive them out, and Petersburg might fall.

The plan was met with great skepticism but Grant did not reject it out of hand. Digging commenced in late June. On July 17, the main shaft reached under the Confederate position. Rumors of a mine construction soon reached the Confederates, but Lee refused to believe or act upon them. For two weeks he debated before directing countermining attempts, which were sluggish and uncoordinated, and failed to discover the mine.

A division of new African-American soldiers was specially trained to carry out the assault once the explosives were detonated. For weeks the division prepared itself for all the chaos potential challenges they might encounter in leading the assault. Despite this intensive training, a decision was made a day before the impending attack to replace the African-American soldiers with another division that was less prepared. Elements within the Union high command lacked confidence in the black soldiers’ combat abilities.

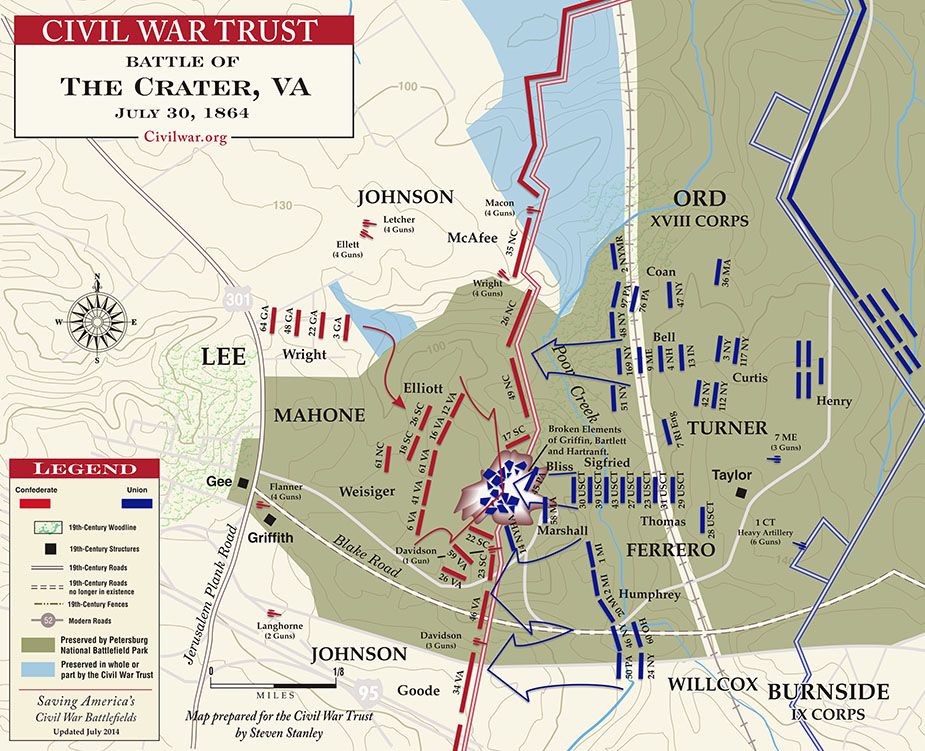

The explosive charges were detonated at 4:44 a.m. on the 30th. They exploded in a massive shower of earth, men, and guns creating a crater that was over 100 feet wide and 30 feet deep. The initial explosive charges immediately killed 278 Confederate soldiers. The remaining troops were stunned by the explosions and did not direct any significant rifle or artillery fire at the enemy for at least 15 minutes. However, the Union troops selected to lead the assault were unprepared for what they encountered. Instead of moving around the crater, they advanced down into it and soon became trapped. The Confederates, under Brig. Gen. William Mahone, regrouped and counterattacked. They began firing rifles and artillery down into the crater in what was later described as a “turkey shoot.” The plan had failed and the battle was lost. However, the strategic situation remained unchanged. Both sides remained in their trenches, and the siege would continue into March of the next year.