On the 29th day of May in the year of our Lord 1453, the Christian stronghold of Constantinople fell to the Muslim Ottoman Turks after a 53 day siege, thus marking an end to Byzantium and the last vestige of the 1500 year old Roman Empire. Enabled by the deep schism in Western Christendom, the conquest of Constantinople opened the door to further Ottoman advances north through the Balkans and an increased and Ottoman naval presence in the Mediterranean putting Christian Europe under constant threat from land and sea for the next 250 years.

The Roman Empire reached its peak of power in the first half of the 2nd century under the rule of emperor Trajan. However, as borders of the empire expanded to include virtually all of the coastline along the Mediterranean Sea and beyond, complications managing the empire also increased. Most notably the constant threat of attack from barbarian tribes outside of the empire such as the Visigoths, Huns, and Vandals.

In 285 AD, Emperor Diocletian decided that the Roman Empire was too big to manage and he divided the Empire into two parts, the Eastern Roman Empire and the Western Roman Empire. Over the next hundred years or so, Rome would be reunited, split into three parts, and split in two again. Finally, in 395 AD, the empire was split into two for good. The Western Empire was ruled by Rome, the Eastern Empire was ruled by Constantinople, named after the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great who in 313 AD issued the Edict of Milan, which granted Christianity—as well as most other religions—legal status in the empire. In 410 AD, the Visigoths attacked and looted the city of Rome. The city was sacked again in 455 AD by the Vandals and in 476 AD after the battle of Ravenna, a Germanic barbarian by the name of Odoacer took control of Rome, deposing the emperor Romulus Augustulus, in what most historians consider the end of the Western Roman Empire and the beginning of the Middle Ages.

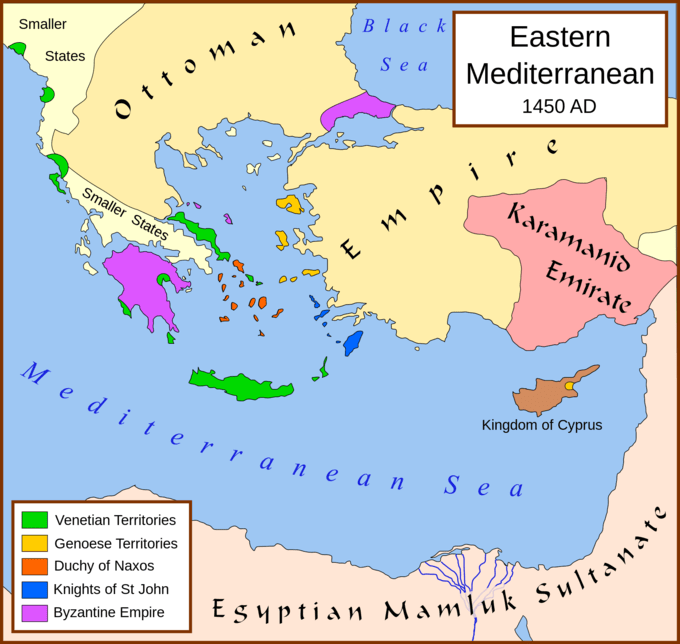

The Eastern half of the empire, which became known as Byzantium, managed to escape much of the barbarian violence that beset Rome because of geography and would survive for almost another 1000 years. Byzantine holdings would expand to include the Balkans, Egypt and parts of North Africa, Anatolia, the Levant, and parts of Italy and the Iberian Peninsula. However, by the mid-15th century Byzantine power had waned considerably weakened by constant struggles for dominance with its Balkan neighbors and Roman Catholic rivals in the West as well as being ravaged by the plague and disease. In the east, the Byzantines lost control of their once vast holdings in the Levant, first to the Arabs, and then in Anatolia to the newly emerging power the Ottoman Turks. The Ottomans had gained control over nearly all Byzantine lands with the exception of Constantinople. However, the Byzantines were granted a reprieve when Tamerlane invaded Anatolia in the Battle of Ankara in 1402 routing the Ottomans and taking the Sultan as a prisoner. The capture of Bayezid I threw the Turks into disorder.

Two decades later, the Ottomans under Sultan Murad II finally laid siege to Constantinople but he was forced to lift it in order to suppress a rebellion elsewhere in the empire. Other contingencies and military defeats would prevent Murad from trying to seize Constantinople again before his death in 1451.

By the time of Murad’s death the Byzantines were exhausted while a new Sutlan, determined to fulfill his father’s vision of conquering Constantinople, Mehmet II, ascended to the throne. In 1452, Mehmet put in motion a number necessary steps to carry out and sustain a siege of Constantinople, which set off alarm in the beleaguered city. Byzantine Emperor Constantine XI appealed to the major Christian powers across Europe for assistance but little would be forthcoming. Few Roman Catholic states felt compelled to assist the Orthodox Byzantines and many turned a deaf ear, including Pope Nicholas V who saw the Byzantines unfortunate predicament an opportunity to push for the reunification of the two churches, a priority of the papacy since 1054.

On April 6, 1453, the Ottoman army, led by the 21-year-old Sultan Mehmed II, laid siege to the city with 80,000 men. Despite a desperate last-ditch defense of the city by the massively outnumbered Christian forces (7,000 men, 2,000 of whom were eventually sent by Rome), Constantinople finally fell to the Ottomans after a two-month siege on May 29, 1453. The last Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI, was last seen casting off his imperial regalia and throwing himself into hand-to-hand combat after the walls of the city were taken.

The capture of Constantinople marked the end of the Roman Empire, an imperial state that had lasted for nearly 1,500 years. The Ottoman conquest of Constantinople also dealt a massive blow to Christendom, as the Islamic Ottoman armies thereafter were left unchecked to advance into Europe without an adversary to their rear. After the conquest, Sultan Mehmed II transferred the capital of the Ottoman Empire from Edirne to Constantinople. Constantinople was transformed into an Islamic city: the Hagia Sophia became a mosque, and the city eventually became known as Istanbul.