On May 17, 1954, the United States Supreme Court issued its landmark decision in the case of Brown vs. the Board of Education of Topeka, that overturned the principle of “separate but equal” that served as the legal cornerstone for the system of racial segregation in the Jim Crow American South. The ruling would inspire and encourage African-Americans to challenge official segregation across the board, giving birth to what would become known as the Civil Rights Movement. It also provoked a violent and determined backlash from white supremacists power structures in the South who vowed a campaign of “massive resistance” to stymie implementation of the ruling.

Origins of Jim Crow

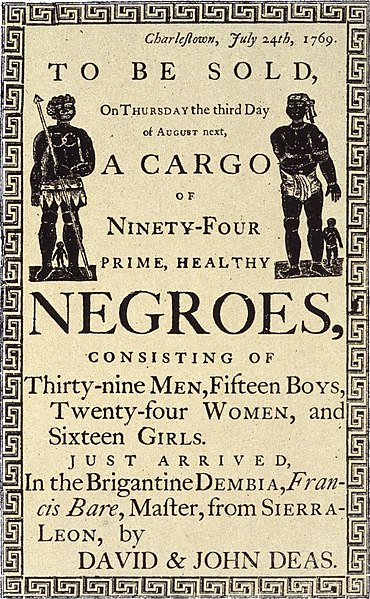

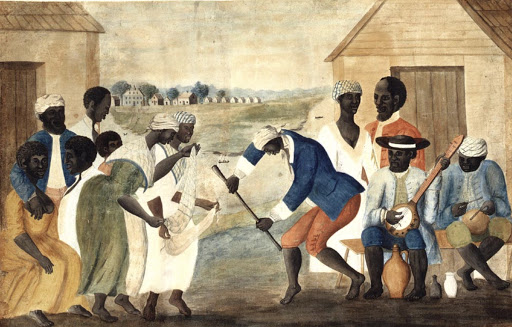

The origins of legally sanctioned racial segregation in the United States, or what would come to be known as Jim Crow, is usually traced back to the infamous 1896 Supreme Court decision in the case of Plessy vs. Ferguson. However, the beginnings of segregation in the South began a decade earlier with a collapse in agriculture prices. This agricultural depression decimated poor white farmers throughout the South and gave rise to a wave of radical populist politicians demanding a more equitable economic system. Wealthy conservative white Southern Democrats who held power in antebellum period and reclaimed their lofty perch after the collapse of Reconstruction, were put on the defensive. With few cards to play and facing a growing threat to their power from an unlikely partnership of poor white farmers and African-Americans, the Democrats turned to the race card and white supremacy to distract, deflect, and divide claiming white civilization was at risk. These Southern, white, Democratic governments passed various laws disenfranchising African-Americans and officially segregating black people from the white population by mandating separate schools, parks, libraries, drinking fountains, restrooms, buses, trains, and restaurants. “Whites Only” and “Colored” signs were constant reminders of the enforced racial order. It was authoritarian rule by one race directed at another.

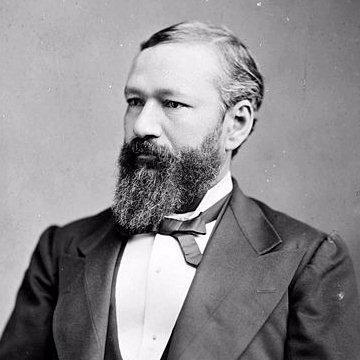

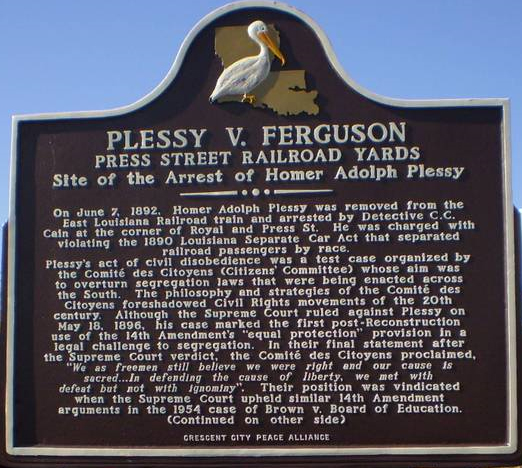

As African-Americans witnessed the pernicious impact of the imposition of racially segregated public facilities, the Black community of New Orleans opted to mount a resistance. In 1890, Louisiana passed a new law that required railroads to provide separate but equal accommodations for white and colored races. Homer Plessy, who was only one-eighth African American but under Louisiana law was considered Colored, decided to test the constitutionality of that law. On June 7, 1892, Plessy agreed to be arrested for refusing to move from a seat reserved for whites. Convicted by a New Orleans court of violating the 1890 law, Plessy filed a petition against the presiding judge, Hon. John H. Ferguson, claiming that the law violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. Ferguson upheld the law and the case slowly made its way up to the Supreme Court.

On May 18, 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court voted 7-1 against Plessy, with the dissenting vote coming from Chief Justice John Harlan. The Court argued that equal but separate accommodations for whites and blacks imposed by Louisiana did not violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment because plaintiff failed to prove that the separate accommodations were indeed inferior and that the protections of 14th Amendment applied only to political and civil rights not “social rights.” In his dissenting opinion, Chief Justice Harlan, a former slaveholder from Kentucky, argued that segregation ran counter to the constitutional principle of equality under the law: “The arbitrary separation of citizens on the basis of race while they are on a public highway is a badge of servitude wholly inconsistent with the civil freedom and the equality before the law established by the Constitution,” he wrote. “It cannot be justified upon any legal grounds.”

Separate but Not Equal

The Supreme Court’s ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson gave an imprimatur of constitutionality to racial segregation but it also carried the seeds of its demise. By the late 1930s, racial segregation in the American South began to come under increased scrutiny. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was determined to dismantle the legal theory of “separate but equal” by demonstrating that separate facilities, especially in the field of education, were in fact inferior and of a substandard quality. Attorney Charles Houston, head of the NAACP legal defense fund and his young protege Thurgood Marshall argued several cases in front of the Supreme Court on a number of cases that they believed would collectively erode segregation. In one case after the next, from 1935-1950, the NAACP repeatedly demonstrated that Southern state government were incapable of meeting the standard of separate but equal. For example, In Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada (1939) Houston argued that it was unconstitutional for Missouri to exclude blacks from the state’s university law school when, under the “separate but equal” provision, no comparable facility for blacks existed within the state. In Sweat v. Painter (1949), Marshall argued that a hastily established law school for African-Americans in Texas did not meet the standard of equality. The Court agreed unanimously arguing that a separate school would be inferior in a number of areas, including faculty, course variety, library facilities, legal writing opportunities, and overall prestige. The Court also found that the mere separation from the majority of law students harmed students’ abilities to compete in the legal arena.

Houston and Marshall’s effort benefited enormously from a Supreme Court had become more progressive since the Plessy ruling, especially after Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed eight out of nine justices during his 12 years in office. Since the end of the Civil War, the court had played a restraining role in the advancement of civil rights, limiting the Federal Government’s ability to protect African-Americans 14th Amendment rights. That trend would begin to reverse by the end of World War II and gather steam by the mid-1950s.

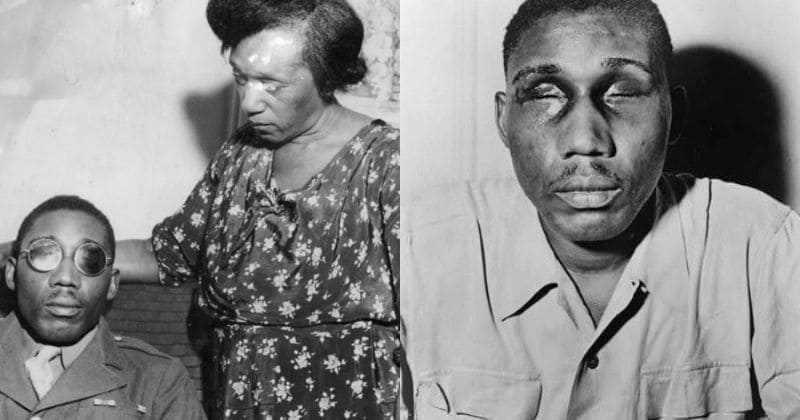

American society was also changing, albeit at a more gradual pace. African-American men volunteered en masse to serve their country in World War I and fought bravely on the frontlines only to return home to a wave of racially motivated violence. African-American men would again unquestioningly heed the call to service in World War II. And when they returned home, they again met a similar fate. This time the beatings and murders of recently returned African American veterans in the South captured national attention, as well as the anger of President Truman, “My stomach turned over when I learned that Negro soldiers, just back from overseas, were being dumped out of army trucks in Mississippi and beaten,” Truman said. “Whatever my inclinations as a native of Missouri might have been, as president I know this is bad. I shall fight to end evils like this.” In a dramatic step, Truman would begin by desegregating the military in 1948.

Truman’s decision to integrate the U.S. military would fracture the Democratic Party and many Southern conservative white politicians who objected to this course organized themselves as a breakaway faction called the Dixiecrats. The Dixiecrats opposed racial integration and sought to maintain Jim Crow laws and white supremacist rule. They even ran an alternative candidate, South Carolina Governor Strom Thurmond in the 1948 presidential election, almost costing Truman the contest. Nonetheless, there were clear signs emerging that legalized racial segregation for the first time was now approaching a fatal rendezvous.

The Decline of Jim Crow

By 1950, the NAACP had amassed cases from Delaware, Virginia, South Carolina, Washington DC, and Kansas challenging the separate but equal standard that were bundled into one case Brown v. Topeka Board of Education. The plaintiff, Oliver Brown filed a class-action suit against the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas after his daughter, Linda was denied entrance to Topeka’s all-white elementary schools. Brown, represented by NAACP Chief Counsel Thurgood Marshall, claimed that schools for Black children were not equal to the white schools, and that segregation violated the so-called “equal protection clause” of the 14th Amendment.

Wrapping up his presentation to the Court, Marshall emphasized that segregation was rooted in the desire to keep “the people who were formerly in slavery as near to that stage as is possible.” Even with such powerful arguments from Marshall the justices were divided on how to rule on school segregation. While most wanted to reverse Plessy and declare segregation in public schools to be unconstitutional, they had various reasons for doing so. Unable to come to a solution by June 1953 (the end of the Court’s 1952-1953 term), the Court decided to rehear the case in December 1953. During the intervening months, however, Chief Justice Fred Vinson died and was replaced by Gov. Earl Warren of California. After the case was reheard in 1953, Chief Justice Warren was able to do something that his predecessor had not—i.e. bring all of the Justices to agree to support a unanimous decision declaring segregation in public schools unconstitutional. On May 14, 1954, he delivered the opinion of the Court, stating that “We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. . .” By overturning the “separate but equal” doctrine, the Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education had set the legal precedent that would be used to overturn laws enforcing segregation in other public facilities.

Massive Resistance Begins

The Brown decision held that school segregation was unconstitutional, but the decision did not explain how quickly nor in what manner desegregation was to be achieved. In May 1955, the Supreme Court issued its implementation guidelines in a decision generally referred to as Brown II. In this ruling the Supreme Court chose not to set a deadline for the completion of desegregation and ordered the lower federal courts to oversee and manage the pace of desegregation “with all deliberate speed,” an ambiguous phrase that left room for a variety of interpretations of the meaning of “deliberate speed.” While Kansas and some other states acted in accordance with the verdict, many school and local officials in the South defied it hoping to drag out implementation as long as possible.

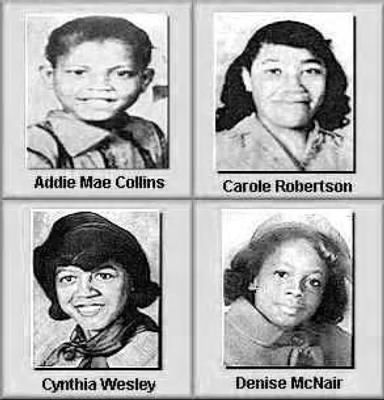

For many Southerners, the Brown decision was tantamount to a declaration of war. In Mississippie Jackson Daily News called the decision “the worst thing that has happened to the South since carpetbaggers and scalawags took charge of our civil government in reconstruction days,” and said it would lead to “racial strife of the bitterest sort.” Mississippi’s powerful Senator James Eastland, declared that “the South will not abide by nor obey this legislative decision by a political body.” In Virginia, Senator Harry Byrd denounced the opinion as “the most serious blow that has yet been struck against the rights of the states in a matter vitally affecting their authority and welfare.” In 1956, 82 representatives and 19 senators endorsed a so-called “Southern Manifesto” in Congress, urging Southerners to use all “lawful means” at their disposal to resist the “chaos and confusion” that school desegregation would cause. In many parts of the South, white citizens’ councils organized to prevent compliance. Some of these groups relied on political action; others used intimidation and violence. In Mississippi, fourteen year-old Emmett Till would become one of the first victims of the supercharged racial tensions following the Brown decision. J.W. Milan, who kidnapped, tortured, and murdered Till only to be found “not guilty” by an all-white jury declared, “Niggers ain’t gonna vote where I live. If they did, they’d control the government. They ain’t gonna go to school with my kids.”

Resistance to the Brown ruling varied from state to state as traditional respect for the rule of law had been overwritten by the misinformed conviction of millions that the Brown decision was not the law of the land but the product of a federal government taken over by conspiratorial and foreign subversives. In Arkansas, Governor Orval Faubus called out the state National Guard to prevent Black students from attending high school in Little Rock in September 1957. After a tense standoff, President Eisenhower deployed federal troops, and nine students—known as the Little Rock Nine entered under armed guard. Troops remained in Little Rock for the 1957-1958 school year. After the troops were withdrawn, however, Governor Faubus closed Little Rock’s public schools for the 1958-1959 school year.

In Virginia, officials passed legislation closing public schools, diverting tax dollars into private academies to pay tuition for white students, while ensuring there was nothing in place for African-American children to receive an education. In Prince Edward County, the public school system would remain closed for five years in which African-American students were educated in activity centers that the African-American community cobbled together.

In Mississippi, the state would resist federal orders to integrate the University of Mississippi and in September 1962, 320 U.S. Marshall’s protected African-American James Meredith as registered at the University. Meredith’s registration would prompt what would become known as the “Battle of Oxford,” in which mobs armed with gasoline bombs, iron bars, rocks, and firearms attacked the marshals and federalize National Guardsmen. The battle raged all night and by dawn, when the mob had been dispersed, two people were killed and 375 injured, 166 of them marshals, 29 by gunshot.

The next year the drama continued in Alabama, where Governor George Wallace stood in the doorway of the Registrar’s office at the University of Alabama to prevent African-Americans Vivian Malone and James Hood tried to register. When Wallace refused to budge, President John F. Kennedy called for 100 troops from the Alabama National Guard to assist federal officials. Wallace chose to step down rather than incite violence.

Beginning of the End

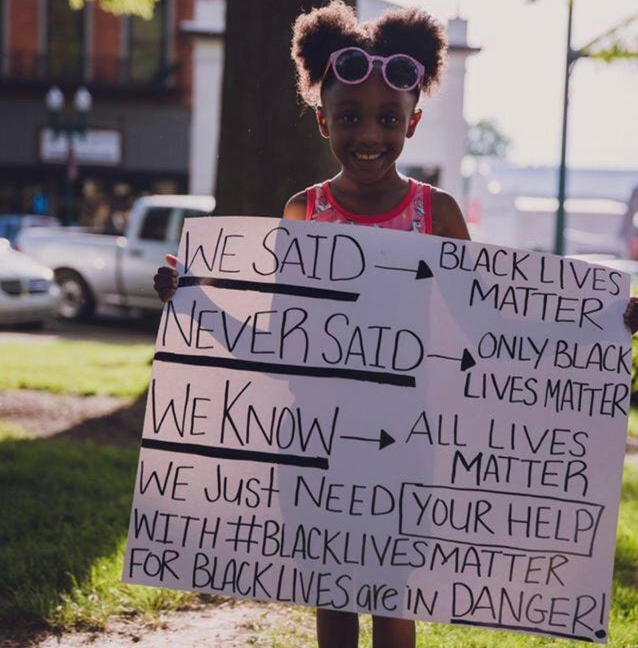

The Brown decision annihilated the separate but equal standard but it fell short of achieving its primary mission of integrating the nation’s public schools. Nevertheless, Brown still remains one of thee most important Supreme Court rulings in the 200 plus year story of our country. By focusing the nation’s attention on subjugation of African-Americans, it helped fuel a wave of freedom rides, sit-ins, voter registration efforts, and other actions leading ultimately to civil rights legislation in the late 1950s and 1960s.