On November 15, 1864, Major General William T. Sherman and his 62,000 man army of grizzled veterans departed Atlanta and began their now famous 300 mile march across the state of Georgia laying a path of destruction that would drive a stake through the heart of the Southern Confederacy and hasten an end to the war.

War is Hell!

Major General William T. Sherman’s capture of Atlanta in early September 1864 was a pivotal moment in the American Civil War. For all intents and purposes, it was a victory that all but ensured the re-election of President Lincoln two months later and squelched any Southern hopes for a negotiated peace on terms favorable to the Confederacy. By the fall of 1864, the Confederacy was in dire straits and Sherman was intent on expediting its demise. Southern morale was at its nadir. The loss of Atlanta was a significant blow and another reminder of the long-standing ineptitude of Confederate military leaders in the West. In Virginia, Confederate military fortunes were growing more dim. The bloody battles of the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Cold Harbor severely degraded the army which now found itself stuck in trenches around Petersburg, surrounded by a more numerous and better equipped foe. There was also an emerging peace movement within some of the Southern states, calling for an end to the war and a reunion with the North. Sherman was convinced the war would only end when Southern political will was broken and the South’s capacity for warfare destroyed. Determined to make Georgia “howl” he developed an audacious plan to break the back of the Confederacy. He would march his 62,000 man army 300 miles across Georgia from Atlanta to Savannah, destroying all the railroads, manufacturing industries, and plantations and farms along the way that were sustaining the Confederate war effort in Virginia.

Sherman’s plan was a bold gambit that carried great risk. He would detach the army from its supply lines and live off the land, as it marched clear across Georgia to Savannah. Both President Lincoln and Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, Sherman’s close friend and commanding officer initially opposed the plan. Even though they recognized its strategic possibilities, they worried that the army could become trapped deep inside hostile territory and cut off from its base of supply. Sherman rebutted these concerns warning that it would be more dangerous to try and occupy Georgia because his army and supply line would be subject to constant guerrilla attacks. However, by destroying Georgia’s railroads, factories, warehouses, and farms, Sherman argued, he could degrade its ability to contribute to the Confederate war effort. After the main Confederate army withdrew into Tennessee, Grant reconsidered his objections. Grant advised President Lincoln that he thought the plan sound and telegraphed Sherman on November 2, “On reflection I think better of your proposition… I say then go on as you propose!”

Sherman and his staff were meticulous in their planning, pouring over census maps that showed county-by-county crop yields, railroads, and manufacturing industries to help guide their foraging and path of destruction. Sherman would later comment, “No military expedition was ever based on sounder or surer data.” Yet Sherman’s foraging plans were not simply about sustaining the army. It was also a psychological operation. Sherman aimed to bring the “hard hand of war” to a civilian population that heretofore had escaped the war’s privations and depredations. He believed that only by unleashing the pain and suffering of the war directly onto the population could he completely undermine Confederate morale and bring the war to a more rapid conclusion. As one of Sherman’s staff observed, “Evidently it is a material element in this campaign to produce among the people of Georgia a thorough conviction of the personal misery which attends war and of the utter helplessness and inability of their rulers, State or Confederate, to protect them.

On to Savannah

As Sherman’s army moved out of Atlanta it laid waste to the business and industrial sector of the city to ensure that the Confederates could salvage nothing of value. Contrary to the image of a city burned to the ground that was popularized by the movie Gone with the Wind, only about 30 percent of the city was actually destroyed by Sherman’s men. Nevertheless, the general clearly was contemptuous of the city which he saw as a symbol of Confederate resistance and a major supply hub, complaining, “Atlanta! I have been fighting Atlanta all this time. It has done more to keep up this war than any—well Richmond perhaps. All the guns and wagons we’ve captured along the way—all marked Atlanta.” Sherman later would proudly describe exiting the city in his memoirs, “Behind us lay Atlanta, smoldering and in ruins, the black smoke rising high in the air and hanging like a pall over the ruined city. Some band, by accident, struck up the anthem of “John Brown’s Body”; the men caught up the strain, and never before or since have I heard the chorus of “Glory, glory, hallelujah!” done with more spirit, or in better harmony of time and place.” Sherman’s path of destruction had begun.

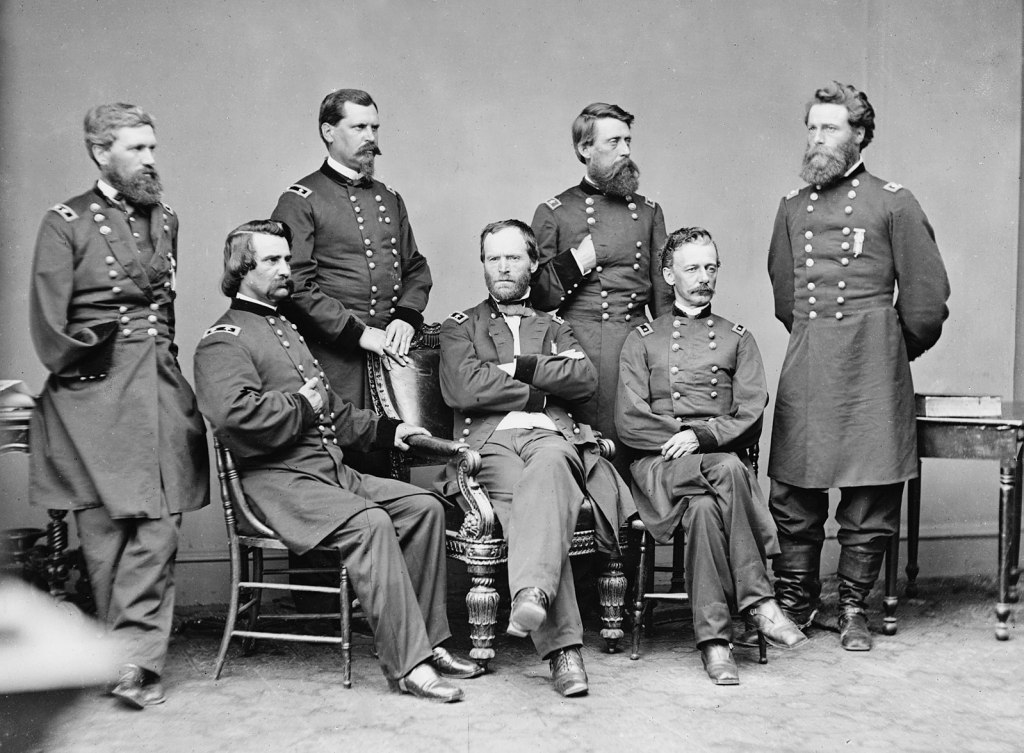

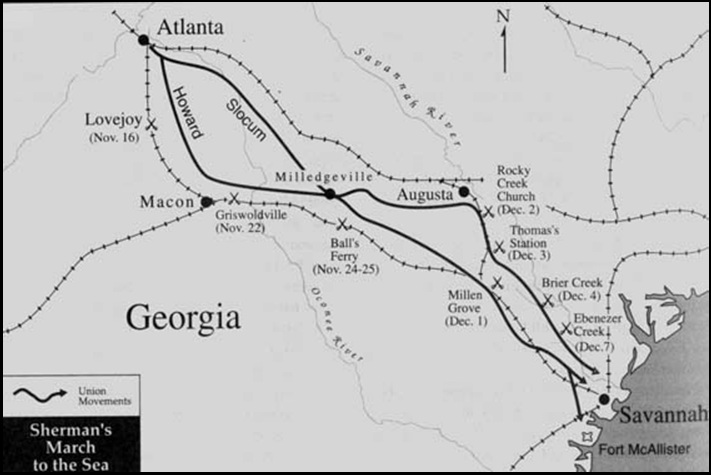

Sherman organized his army into two roughly equivalent wings of 30,000 troops and marched his forces south toward Savannah, keeping the two wings about 30 miles apart to confuse the enemy and obscure his intentions. The right wing—the Army of Tennessee—was commanded by Major General Oliver Howard and consisted of the XV and XVII Corps. The left wing—the Army of Georgia—was commanded by Major General Henry Slocum and was made up of the XIV and XX corps. In addition, Sherman also had two brigades of cavalry under Brigadier General H. Judson Kilpatrick. Together, Sherman’s forces significantly outnumbered the 13,000 Confederate cavalry, infantry, and local militia that Confederate commanders from the Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida were able to scratch together. In fact, Georgia’s rivers, creeks, and swamps would prove to be greater obstacles to Sherman’s advance than any Confederate military force.

True to his promise, Sherman’s army lived off the land as it cut a thirty mile wide path of destruction through Georgia, pillaging farms and plantations while destroying high value targets such as railroads, factories, telegraphs, mills, cotton gins, and warehouses. Union troops would heat the torn up iron rails until they were redhot and bend them into contorted shapes know as “Sherman’s neckties” leaving a trail of this twisted iron as they advanced. At the same time, Sherman ordered his troops to “forage liberally” and issued Special Field Order 120 which required every brigade to organize a foraging detachment under the direction of one of its more “discreet” officers with a goal of keeping a consistent three-day supply of gathered foodstuffs. Other ill-disciplined soldiers hunted for jewelry, silverware, and other concealed valuables. These foragers quickly became known as “bummers” as they ransacked farms and plantations across rural Georgia, striking fear and anger among the Georgian people. Sherman’s army needed the supplies, but they also wanted to teach Georgians a lesson: “it isn’t so sweet to secede,” one soldier wrote in a letter home, “as [they] thought it would be.”

Sherman’s army encountered its first organized military resistance on 22 November near the town of Griswoldville, which was home to a pistol and saber factory. A desperate group of 3,000 Georgian militia, mostly old men and teenage boys, attacked the smaller rear guard of the right wing of Sherman’s army. Although the Confederates outnumbered Sherman’s rearguard by almost 2:1, they were facing experienced troops armed with new Spencer repeating rifles. The Confederates charged the Union line three times with disastrous results, including 650 men killed or wounded compared to 62 casualties on the Union side. The results were so tragically lopsided that Southern troops largely refrained from initiating any further battles beyond cavalry skirmishes. Instead, they fled South ahead of Sherman’s troops, wreaking their own havoc as they went: They wrecked bridges, chopped down trees and burned barns filled with provisions before the Union army could reach them.

As Howard’s right-wing repulsed the futile Confederate attack on its rear guard, Slocum’s wing advanced toward the Georgian state capital at Milledgeville. Georgia’s governor and other state officials urged bold resistance from the public but as Slocum’s troops approached the outskirts of the capital, the governor and legislators quickly fled. On November 24, Slocum’s wing entered Milledgeville where they celebrated Thanksgiving, much to the chagrin of the local populace, and enacted a mock legislative session in the statehouse where they pretended to vote Georgia back into the union.

Over the next few weeks, Sherman’s army advanced steadily toward Savannah, meeting with only minimal resistance. Kilpatrick’s cavalry beat back repeated attacks from Confederate horsemen while Sherman’s engineers and pioneer brigades proved exceptionally adept at pontooning rivers and clearing the many obstacles deliberately placed in their path. The army marched from sun-up to sun-down, covering as many as fifteen miles a day. The men traveled light. Each man carried a musket and about 40 rounds in his cartridge box but to speed their way they reduced their discretionary holdings largely to a change of undergarments, their individual mess kit, and a shelter half which they typically wrapped up in their blankets slung across their left shoulder. Meals were limited to a sparse breakfast and a supper at the end of the day. There were no breaks for lunch and the men were expected to eat whenever and whatever they could on the march. When the army did stop it was usually reserved for foraging or some act of destruction.

A Moment of Shame

Sherman’s advance also attracted a growing number of escaped slaves, who greeted them as emancipators, and followed behind the army for protection as it pushed toward Savannah. These followers set the stage for one of the more shameful episodes of the entire war. On December 9, the left wing of Sherman’s army approached Ebeneezer Creek with a large body of Confederate cavalry nipping at its heels. The creek had become swollen and impassable without a bridge. Union Brig. General Jefferson Davis, who commanded the 14th Army Corps ordered his engineers to quickly assemble a pontoon bridge so the army could cross and escape further harassment. Once the bridge was completed, Davis ordered his men to quickly cross over the creek. After the last Union soldier made it across the creek, Davis ordered his men to cut the ropes of the bridge leaving behind 800 former slaves that were soon massacred by the Confederate cavalry. Several Union soldiers on the other side of the creek tried to help, wading in as far as they could to pull in those on floating devices and pushing logs out to the few refugees still swimming but these efforts proved futile. Those who were were not killed by the Confederates that day were captured and returned to slavery. Davis was never reprimanded for this cowardly shameful act an in fact Sherman defended him, blaming the freed slaves for ignoring his advice not to follow the army.

Less than two weeks later, Sherman and his army had reached the outskirts of Savannah. The 10,000 Confederate soldiers who were responsible for defending the city abandoned their trenches and quickly fled north into South Carolina. On December 21 Savannah’s mayor formally surrendered the city to Sherman. In a telegram to President Lincoln, Sherman wrote, “I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the City of Savannah, with one hundred and fifty heavy guns and plenty of ammunition and about twenty-five thousand bales of cotton.”

The Move North

Sherman’s march proved to be an unqualified success while its destructive impact was staggering. It devastated the war making potential of the Confederacy and demoralized the Southern Civilian population and in doing so hastened an end to the war. Sherman, by his own account, estimated a total Confederate economic loss of $100 million (more than $1.5 billion in the 21st century) in his official campaign report. His Army destroyed 300 miles (480 km) of railroad, numerous bridges and miles of telegraph lines. It seized 5,000 horses, 4,000 mules, and 13,000 head of cattle. It confiscated 9.5 million pounds of corn and 10.5 million pounds of fodder, and destroyed uncounted cotton gins and mills. Between 17,000-25,000 slaves were also liberated.

Sherman and his army remained in Savannah for a month, gathering its strength before turning North to unite with General Grant’s army in Virginia and crush the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia once and for all. Sherman and cut a similar path of destruction through the Carolinas. One Georgian woman, Emma Florence LeConte, after the fall of Savannah, wrote in her diary, ”Georgia has been desolated. They are preparing to hurl destruction upon the State they hate most of all, and Sherman the brute avows his intention of converting South Carolina into a wilderness.” In some respects his march through South Carolina was much worse than Georgia because South Carolina was the first state to secede from the Union and was responsible for the rebellion. Marching through the South Carolina capital of Columbia, Sherman left the city a charred ruin. Sherman denied any responsibility for the burning of Columbia. He claimed that the raging fires were started by evacuating Confederates and fanned by high winds. Sherman later wrote: “Though I never ordered it and never wished it, I have never shed any tears over the event, because I believe that it hastened what we all fought for, the end of the War.”

Sherman entered North Carolina where he proceeded to engage the second largest Confederate Army under General Joe Johnstone. However Johnstone’s army was no match for Sherman’s men. Johnstone’s men were outnumbered three to one and completely demoralized. Johnstone told Confederate President Jefferson Davis, “Our people are tired of the war, feel themselves whipped, and will not fight. Our country is overrun, its military resources greatly diminished, while the enemy’s military power and resources were never greater and may be increased to any extent desired. … My small force is melting away like snow before the sun.” On April, 26, 1865, Sherman accepted Johnstone’s surrender, less than three weeks after Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox. It was the virtual end for the Confederacy, although some smaller forces west of the Mississippi River. The war was over.