On the evening of October 16, 1859, the radical abolitionist John Brown and a band of like-minded co-conspirators quietly slipped into the sleepy Virginia town of Harpers’ Ferry. Nestled between the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers, Harper’s Ferry was home to a U.S. armory and rifle works. Their plan was simple, seize the federal arsenal and use the weapons to foment a slave insurrection throughout the South that would destroy the institution of slavery once and for all. Although Brown and his men would ultimately fail in their mission, the raid would send shockwaves throughout the country, and drive it down an almost irrecoverable path towards certain civil war.

A Nation on the Brink

The United States in the decade before the Civil War was a country fraying apart at the seams. It was an increasingly polarized nation bitterly divided over the issue of slavery, which permeated all political discourse and debate. The Founding Fathers largely sidestepped the issue of slavery at the Constitutional Convention in order to create a document acceptable to all. However, in doing so they left a number of questions unanswered, most importantly the extension of slavery. In a number of compromises designed to placate slaveholders, the Constitution implicitly endorsed the institution of slavery where it already existed, but it said nothing about whether slavery would or would not be allowed in any new territories or states that might enter the union subsequently. As the nation steadily expanded its frontiers in the first half of the 19th century, that question alone tore the nation asunder, especially because with the admission of each slave or non-slave state the existing balance of power between pro-slavery and anti-slavery forces shifted. As such, American politics became a constant struggle between pro-slavery and anti-Slavery forces for political power and what side would gain the upper hand. The tension inside the country was summed up succinctly by the New York Tribune publisher, Horace Greeley, in 1854, “”We are not one people. We are two peoples. We are a people for Freedom and a people for Slavery. Between the two, conflict is inevitable.”

The 1850s were a particularly tumultuous decade that only served to sharpen the dividing lines between those who supported slavery and its unlimited expansion and those who did not. For the opponents of slavery, the decade was a series of setbacks that only served to increase their anger. In 1850, Congress adopted a controversial Fugitive Slave Law as part of a larger compromise to admit California to the union as a free state. This new law drew the scorn of many northerners because it forcibly compelled all citizens to assist in the capture and return of runaway slaves. In 1854, the Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed allowing people in the territories of Kansas and Nebraska to decide for themselves whether or not to allow slavery within their borders, effectively invalidating the 1820 Missouri Compromise, which precluded the admission of any new slave states north of Missouri’s southern border. The act would touch off a bloody guerilla war in Kansas between pro and anti-slavery forces while infuriating many northerners who considered the Missouri Compromise to be a binding agreement. Three years later the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in its infamous Dred Scott decision, that the Federal Government had no authority to restrict the institution of slavery. All of these developments only served to convince the more radical anti-Slavery elements that the Federal Government was under the thrall of “slave power,” a cabal of wealthy Southern slaveholders who wielded disproportionate influence in Washington and that more deliberate and decisive action would be needed to end slavery.

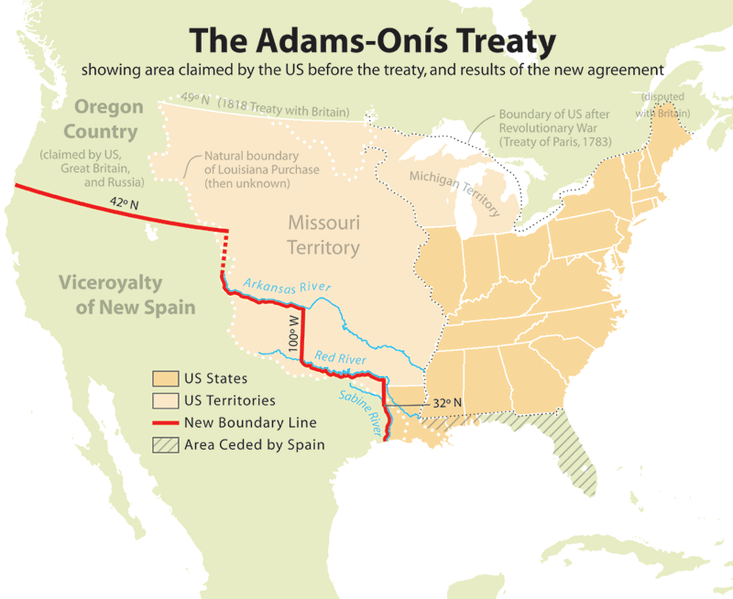

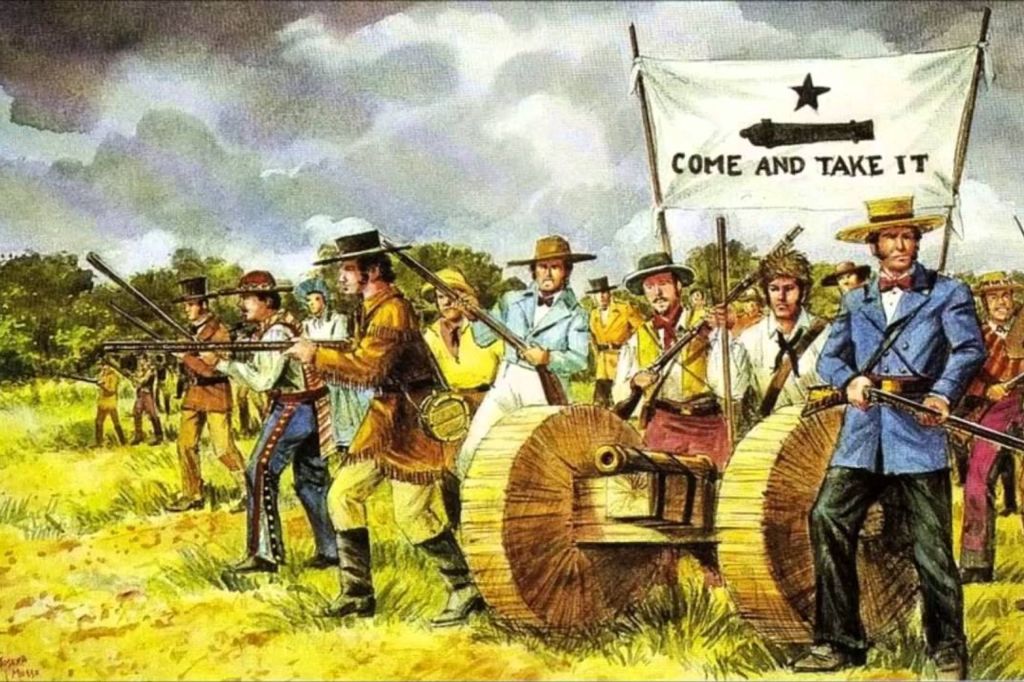

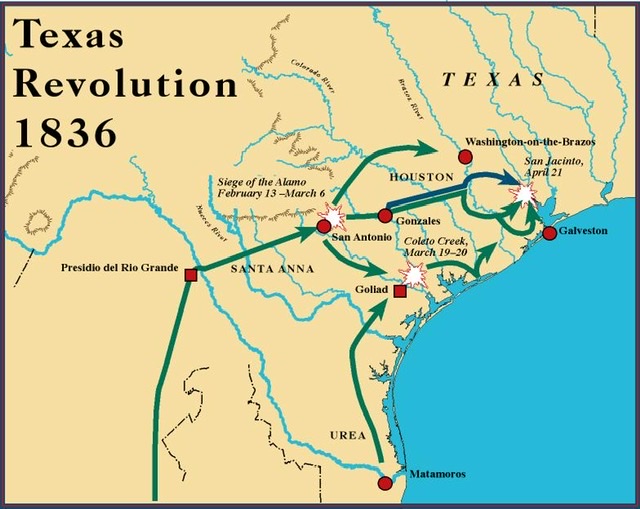

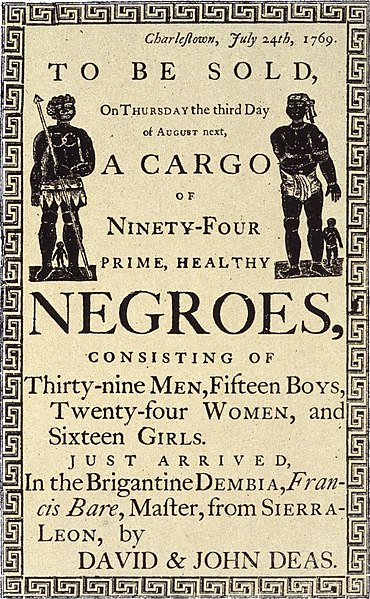

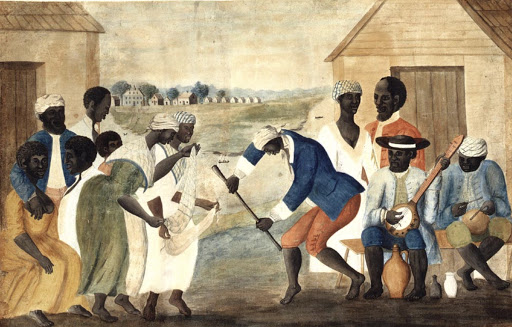

For all the angst that permeated the abolitionists and the anti-slavery forces about the disproportionate influence that the South wielded over the Federal government, pro-slavery elements were equally uneasy about their standing. The slave holding states continued to view Northern abolitionists as a persistent threat to their prosperity and way of life. They clearly understood that if slavery did not continue to expand they would soon find their political power and their ability to defend their interests eroded with the admission of each new free state to the union. Southerners enthusiastically supported the annexation of Texas in 1845 and most favored war with Mexico a year later as a means to acquire more territory to create additional slave states, despite opposition from anti-slavery forces in the north. At the same time, increasingly aggressive agitation by Northern abolitionists stoked ever present fears in the South of violent slave insurrections. For many in the South, memories of Nat Turner’s 1831 slave revolt in southern Virginia in which Turner and his accomplices killed 55 white men, women, and children were still fresh.

The Making of an Anti-Slavery Crusader

It is against this backdrop of a sharply divided nation, that John Brown would enshrine his place in American history as a key figure in the struggle against slavery and the road to disunion. Brown was a complicated man, part patriarch, zealot, warrior, terrorist and visionary all rolled into one. Gaunt and haggard in appearance, and with a flowing white beard, Brown cut the image of an American Moses who would lead the slaves out of bondage. Driven by a fervent belief that slavery was immoral and an abomination, Brown saw himself as an “instrument of God’s will” in the war against slavery and dedicated himself to eradicating it by any means necessary.

Brown’s abolitionist identity formed at an early age but it would evolve in a more radical direction as the nation’s sectional divide over slavery intensified. Born in 1800 in Connecticut, he grew up in a deeply religious Calvinist family with overtly strong anti-slavery views. In 1805, Brown’s family relocated to Hudson, Ohio a key stop on the Underground Railroad where he and his father, Owen, became more directly involved in efforts to bring the slaves to freedom. At the age of 12, Brown had his first real encounter with the evils of slavery, witnessing the beating of an African-American boy, who was about his age. Brown recalled that the boy was “badly clothed, poorly fed, and beaten before his eyes.” Outraged at what he had seen, Brown swore “eternal war with slavery.” However, it was until the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law in 1850 and the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854 that Brown would make a name for himself within abolitionist circles.

Terror of the Kansas Prairie

Even though Brown continued to make a name for himself within abolitionist circles, it was not until 1856 when the territory of Kansas became a battleground between pro and anti-slavery forces that he became a figure of national significance. Like many others at the time, Brown was outraged by the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which he saw as nothing more than a betrayal of the Missouri Compromise and a craven capitulation to the slaveholding caste by the highest levels of government. In 1855, Brown’s sons—John, Jr, Jason, Frederick, Owen, and Salmon—immigrated to Kansas in search of new economic opportunities and to advance the free-soil cause. Brown struggled with the decision of whether or not to follow his sons to Kansas. At 55, he was an older man and as the patriarch of such a large family, he was also responsible to provide for the welfare of his wife and his younger children. He also was still committed to making the North Elba settlement a success. Nonetheless he could not shake the sense that Kansas would become ground zero in the struggle against slavery. In the end Brown, chose not to follow sons, opting instead to focus his energy on the North Elba project. However, it was also clear that he harbored no objections to their move declaring, “If you or any of my family are disposed to go to Kansas or Nebraska, with a view to help defeat Satan and his legions in that direction, I have not a word to say; but I feel committed to operate in another area of the field.”

Yet as Kansas descended deeper into violence and chaos, Brown could not resist the gravitational pull of the fight. By early spring 1855, the situation was becoming increasingly volatile as hundreds and thousands of well-armed, pro-slavery, “Border Ruffians” crossed over from Missouri on the eve of legislative elections seeking to intimidate Kansas’ anti-slavery settlers, known as Jayhawkers, and to cast fraudulent ballots to impose a pro-slavery state government. In May, Brown received an urgent letter from his son, John Jr., asking for more guns, ammunition, and money to counter the growing threat. “Every slaveholding state is furnishing men and money to fasten slavery upon this glorious land by means no matter how foul,” his son wrote. Not one to shrink from a fight, especially against slavery, Brown was determined to fulfil his son’s request and decided he would deliver the goods himself. That June, Brown attended an abolitionist convention in Syracuse, New York, where he sought to drum up financial support to help purchase firearms and ammunition for his sons and other anti-slavery settlers. He spoke feverishly about the deteriorating situation in Kansas and circulated his son’s letter for added effect. Initially, many of the convention participants were reluctant to respond favorably to Brown’s pleas, fearing that more weapons would only further enflame the situation. At the end of the day, Brown persuaded enough participants to contribute to the cause and he made preparations to travel to Kansas. In August, John Brown loaded up his wagons and headed west with his son Oliver and son in law Henry Thompson. “I’m going to Kansas,” he declared, “to make it a Free state.”

On 21 May, over 800 pro-slavery ruffians led by former U.S. Senator from Missouri David Atchison descended upon the abolitionist stronghold of Lawrence Kansas and proceeded to ransack the town. Thundering into town uncontested, they terrorized the citizenry, looted homes and businesses, and destroyed two newspaper offices, tossing the printing press of an abolitionist newspaper into a nearby river. As the coup de grace, they destroyed the Free State Hotel, built by the abolitionist Emigrant Aid Company, as a temporary residence for newly arrived anti-slavery settlers.

News of the heinous attack spread quickly. Brown and his sons rushed to the defense of the town but were too late to prevent its destruction. Brown was furious. He was appalled by the damage that was done but he was equally incensed that not a single abolitionist fired a gun in defense of the town. About the same time, news from Washington reached Kansas that abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner was nearly beaten to death with a cane by pro-slavery Congressman Preston Brooks, while giving a speech on the Senate floor titled “The Crimes Against Kansas.” Both of these incidents only served to reinforce his belief in the Old Testament concept of justice, “an eye for an eye,” and the folly of non-violent abolitionism.

The attack on Lawrence was a turning point for Brown. One that would put him firmly and irreversibly on the path to a violent war against slavery. No longer willing to sit idly by and frustrated by the caution and inaction of leadership of Kansas’ free state movement, Brown vowed to retaliate for the attack on Lawrence. “Now something must be done… Something is going to be done now,” he told a small group of followers.

In Brown’s mind, pro-slavery forces needed to be taught a lesson, one that would resonate and not be easily forgotten. His next step would thrust him into national prominence and bring about his vision of a violent war against slave power in Kansas. On May 24, Brown, along with four of his sons and three other anti-slavery men descended upon a pro-slavery settlement along Pottawattamie Creek to exact their revenge. There, in the middle of the night, they dragged five pro-slavery men from their homes and brutally executed them with broad swords. Word of what would become known as the Pottawattamie Massacre, quickly spread. Brown repeatedly denied involvement in this criminal action but his growing militant reputation and that of his family made them prime suspects.

The executions did not have the intended “restraining effect” that Brown sought. Instead they ushered in an extended period of retaliatory violence known as “Bleeding Kansas,” in which the Brown family would play a leading role. In early June, Brown and a band of free-state militia ambushed the camp of a pro-slavery ruffians who were hunting down Brown and his family in response to the Pottawatomie Massacre. After a three-hour gun battle, Brown and his militia defeated the pro-slavery forces in what would become known as the Battle of Black Jack. It was what Brown himself called, “the first regular battle between Free-State and proslavery forces in Kansas” and what would become the opening salvo in his war against slavery.

Over the next six months, Brown steadily emerged as a national symbol in the struggle against slavery as the conflict between pro-slavery and anti-slavery partisans spread across the Kansas prairie. Brown’s standing would peak in August when several hundreds of pro-slavery fighters attacked the free-state settlement of Osawatomie, where Brown resided. With only forty men available, he led a vigorous but unsuccessful defense of the settlement. Although Brown was unable to prevent the destruction of Osawatomie, he did manage to score a major propaganda victory. By the end of the year, Brown was one of the most beloved or hated figures in Kansas. Back east, he had achieved the status of a cult figure among some New England abolitionists and was now known as “Osawatomie Brown” or “Old Osawatomie” and Broadway plays were written about him. Nevertheless, Brown’s rise to prominence was not without great personal cost. In the course of the struggle for Kansas, he lost his son Frederick who was ambushed alone by pro-slavery partisans and his son-in-law Henry Thompson who was mortally wounded at the Battle of Black Jack.

By 1857 the situation in Kansas was stabilizing as free-state forces gained the upper hand. Brown and three of his sons returned east in November 1856, and spent the next two years going back and forth from Kansas to New England raising funds. Brown couched his requests for support it terms of helping free-state settlers in Kansas but in reality he planned to use the money to fight slavery elsewhere. Brown’s experiences in Kansas only further convinced him that the war against slavery could and should be taken to the South where a major blow against the entire system of slavery might be struck. Brown’s focus once settled on Harper’s Ferry.

The Die is Cast

Brown secured the backing of six prominent abolitionists, known as the “Secret Six,” and assembled an invasion force. His “army” grew to include 22 men, including five free Black men and three of Brown’s sons. Among the five free Black men was Dangerfield Newby who joined Brown’s band after his efforts to purchase the freedom of his wife and seven children who were enslaved in Virginia failed. Brown hoped to recruit Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman to his cause boasting, “When I strike, the bees will swarm.” Ultimately, Douglass and Tubman refused to join Brown’s endeavor, sure that the venture would fail. Undeterred, Brown and his co-conspirators rented the Kennedy farm in Maryland, across the river from Harpers Ferry and prepared for their raid.

Brown and his cohorts entered Harpers Ferry under the cover of night the evening of Sunday, October 16. They cut the town’s telegraph wires and quickly seized control of the unsuspecting armory. After taking control of the armory, Brown sent small detachments of men to kidnap several prominent local slave owners, including Col. Lewis W. Washington, a great-grandnephew of the first president. The following morning, the residents of Harpers awoke to news that their town had been overrun by radical abolitionists. Word of the raid quickly spread and armed militia units from nearby Shepherdstown, Martinsburg, and Frederick, Maryland poured into town. Brown and a dozen of his men found themselves surrounded, holed up in a small brick engine house with stout oak doors. Later that night a company of 90 U.S. Marines arrived, led by Colonel Robert. E. Lee and Lieutenant JEB Stuart, and took command of the situation.

Trapped in the engine house, the situation was becoming more bleak. Only four of Brown’s men remained unwounded while the bloody corpses of the slain, including Brown’s 20-year-old son, Oliver, lay on the floor of the engine house. Another son, Watson, lay mortally wounded. On the morning of the 18th, Lee sent Stuart forward under a flag of truce to negotiate Brown’s surrender. Brown asked that he and his men be allowed to retreat across the river to Maryland, where they would free their hostages. Stuart promised only that the raiders would be protected from the mob and receive a fair trial. “Well, lieutenant, I see we can’t agree,” replied Brown.

With Brown now refusing to surrender, Lee ordered the Marines to storm the engine house. In the melee that followed Brown and his cohorts were overwhelmed by the Marines. The whole affair lasted three minutes. Of the 22 men who slipped into Harpers Ferry less than 36 hours before, seventeen men died in the fighting and five, including Brown himself, were taken prisoner. Brown was indicted for treason, first-degree murder and “conspiring with Negroes to produce insurrection,” on October 25. He and his other surviving followers were hanged before the end of the year.

John Brown on Trial

Given the horror and the demands for immediate justice that Brown’s actions provoked in the South, he was quickly brought to trial in Charles Town, Virginia on October 26. In less than a week, Brown was found guilty of treason, first-degree murder and “conspiring with Negroes to produce insurrection.” He was sentenced to death. On December 2, Brown exited the Charles Town jail and escorted to the gallows under the armed guard of six companies of infantry. Before his execution, he handed his guard a slip of paper that read, “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.” Around 11:00 am, a sack and rope were placed on Brown’s head and around his neck. Brown told his guard, “Don’t keep me waiting longer than necessary. Be quick.” And with those words, Brown passed into history.

Brown’s execution stirred strong contradictory emotions in the North and South. In the North, Brown was celebrated as a martyr in the righteous war to end slavery. In the South he was reviled as the manifestation of the region’s worst nightmare. His words would prove prophetic. In little over a year later Lincoln would be elected President, South Carolina would secede from the Union and the nation plunged into civil war.