On September 12, 1683, a combined Polish-German army under the leadership of the King of Poland, Jan Sobieski, routed the Ottoman Turks at the Battle of Vienna. For two months, the capital of the Habsburg Monarchy, was besieged by the Ottomans and brought to the point of near surrender before Sobieski’s relief force shattered the Turkish lines, breaking the siege. The battle would prove to be one of the most pivotal in history, a climactic struggle between Christianity and Islam, that would thwart any further Turkish expansion into Europe and put in motion what would become the slow steady decline of the Ottoman Empire over the next 200 years.

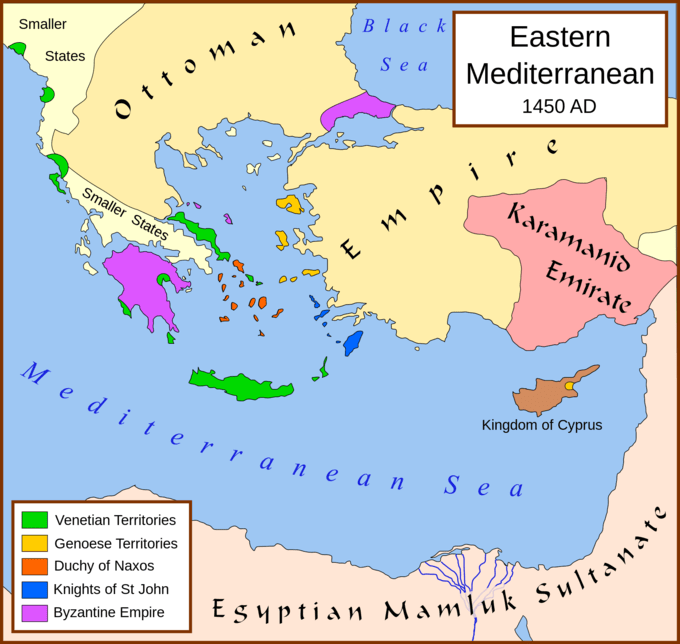

The Ottoman Empire was an aggressively expansionist power that sought to expand beyond its strongholds in Anatolia, the Near East, and the Levant and into the heart of Europe. The Ottomans first crossed the Bosporus and into Europe in 1346, sweeping through the Balkans, subjugating the Serbs, Greeks, Bulgarians, Albanians and other peoples. In May 1453, the Turks seized Constantinople, after an epic siege, closing the curtain on the once powerful Byzantine Empire and putting all of Europe on notice. Over the next century, the Ottomans, under Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent continued their steady advance northward, conquering the Kingdom of Hungary at the Battle of Mohacs in 1526 before finally being halted at the gates of Vienna in 1529. This was the first defeat inflicted on Suleiman, sowing the seeds of a bitter Ottoman–Habsburg rivalry that lasted until the 20th century. In 1566, the Habsburgs once again defeated Suleyman’s army at the battle of Szigetvár again forcing the Ottomans to retreat. However, Ottoman power was beginning to wane and a series of weak Sultans, palace intrigues, and unrest in other far corners of the empire precluded any further advances into Europe for 150 years.

Europe in the mid-17th century was weak, divided, and vulnerable to the Ottoman threat. The Thirty Years war between Catholics and Protestants that ended with the 1648 peace of Westphalia decimated the continent. By the second half of the century, much of Central Europe was still in rebuild mode; relations between Catholics and Protestants remained bitter and France and the Hapsburgs continued to vie for supremacy on the continent. Under these conditions, the Ottoman Sultan Mehemet IV accepted the recommendation of his overly ambitious Grand Vizier (Prime Minister) Kara Mustafa Pasha, that the time had come again to launch a major military campaign against the House of Habsburg. The Sultan sent notice to Habspurg Emperor Leopold I of his intentions, as was practice before declaring Jihad, and personally threated to take the emperor’s head. He also warned Leopold that he would kill the population of Vienna in its entirety unless they accepted Islam.

In late March of 1683, Kara Mustafa, now Serasker or Supreme Commander, and his 170,000 strong army departed Adrianople on the Tonsus river and began their long march north to Vienna. The march was onerous and slow going hampered by early Spring rains, poor roads, disease and illness and an extensive supply train. The Ottoman army reached Belgrade on May 3 where it was reinforced by the arrival of additional Tatar, Arab, Bosnian, Romanian vassals and Hungarian protestants in rebellion against the Habsburgs. After a month of incorporating these new reinforcements, the army resumed its march North, advancing quickly across the Hungarian plain. When word reached Emperor Leopold that the Ottoman Army was approaching Vienna more swiftly than expected he quickly fled the capital for the safety of Linz 135 miles away. Another 60,000 residents allegedly followed suit soon after. In his stead, Leopold left behind a garrison of 15,000 troops under the command of Count Ernst Rüdiger von Starhemberg. Starhemberg was an experienced if not ordinary commander, but he exhibited a steely resolve and swore to “fight to the last drop of blood.”

Kara Mustafa and his army reached the outskirts of Vienna on July 14, one week after Leopold fled the city. He immediately demanded the city surrender, urging the defenders to “accept Islam and live in peace under the Sultan!” Starhemberg and his men vigorously rejected his appeal and over the next two days the Ottoman army encircled the city and prepared for an epic siege. Mustafa focused the Ottoman attack on what he considered to be the most vulnerable section of Vienna’s wall, the southwest. He ordered his artillery forward and once in position his guns began to bombard the city wall but with only marginal effect. The Turks were excellent artillerists, but the caliber of their artillery was too small to bring down Vienna’s reinforced stone wall. Instead, Mustafa altered his strategy and directed his engineers to dig a network of trenches and tunnels, directly toward the city so that they could detonate explosives under Vienna’s wall and exploit any potential breeches. At the same time, Turkish archers fired their arrows indiscriminately over the wall and into the city while the Janissaries fired their arquebuses at the defenders along the wall.

For several weeks, Vienna’s defenders successfully beat back repeated enemy attacks but by early September their situation had become increasingly more desperate. Food, water, and ammunition were in short supply. Disease was rampant throughout the city and only a third of Starhemberg’s men remained fit for duty. All the while the Ottoman siege lines inched steadily closer.

On September 2, Ottoman engineers finally managed to blast several gaps in a large section of the wall and two days later elite Turkish Janissaries almost penetrated into the city through a 30-foot breech before being driven back by a countercharge led by Starhemberg himself. The situation reached a critical point on September 8, when the Ottomans seized key defensive positions near the city walls. Anticipating a breach in the city walls, the remaining defenders prepared to fight inside the city hand to hand. For the next three days Ottoman forces pressed hard to break into the city but were repelled by the yeoman efforts of Starhemberg’s exhausted troops. The city was on the verge of surrender and the Ottomans on the threshold of a great victory. Vienna’s only hope was the timely arrival of the anxiously awaited relief army.

As all these events were transpiring, the diplomatic efforts of Leopold and Pope Innocent XI were paying dividends as a relief army was gathered northwest of Vienna on September 11, under the guise of the Papal sponsored Holy League. Here, roughly 40,000-50,000 troops from the German states of Bavaria, Saxony, Franconia and Swabia and 18,000 Hapsburg troops under the very capable command of Charles V, Duke of Lorraine joined with 18,000 Polish soldiers, including Poland’s famous Winged Hussars (Heavy Cavalry) under King Jan Sobieski. Sobieski assumed command over the entire relief force given his lofty status and prepared to relieve the beleaguered city the next day.

Kara Mustafa did not take the threat of the relief army seriously enough and refused to give up his dream of taking Vienna once and for all. He rejected the advice of his commanders to give up the siege and focus on the threat posed by Sobieski’s Army. Instead, he kept up the pressure on Vienna, diverting only six thousand infantry, twenty-two thousand Tatar cavalry, and six cannons, to confront the relief force. Moreover, no field fortifications were created, and no defensive lines established. The Ottoman camp was completely open to attack.

Early on Sunday, September 12, the Holy League army began their assault on the largely unprepared and poorly defended Turkish encampment. The left wing of the army under the command of Charles, the Duke of Loraine, struck first. A mix of Imperial Habsburg and Saxon infantry moved downhill bearing a huge white banner with a scarlet cross, the Army of Christ Crucified. The center, composed of Bavarian and Franconia troops followed and one Ottoman military official watching the advance from afar remarked, “It looked as if a flood of black pitch was pouring downhill crushing and burning everything that opposed it.” After sweeping away Ottoman skirmishers, the Holy League force engaged their Ottoman foes demonstrating a tenacity the Turks had not seen before. After heavy fighting and repelling multiple Ottoman counter attacks, the Christians inflicted significant losses on the Ottomans and were poised for a breakthrough by mid-Afternoon.

On the right, the rugged and ravine filled terrain of the battlefield delayed the arrival of the Poles and their cavalry. By 4:00pm the Poles finally reached flat and easy ground suitable for their horses and formed up ready to enter the fight. After praying the rosary, Sobieski sent forward a detachment of 120 hussars—heavy cavalry—to probe for weaknesses in the Ottoman line. The hussars inflicted and received many casualties but demonstrated that the Ottoman lines were weak and vulnerable.

The climactic scene of the battle occurred around 6:00 when Sobieski launched one of the largest cavalry charges in history. Approximately 18,000 horsemen, including 3,000 heavy Polish Lancers or Winged Hussars, led by Sobieski himself, thundered across the battlefield towards the beleaguered Ottoman camps. The charge was massive but meticulously timed, coinciding with a coordinated push by the German and Habsburg forces from the north, who by this time had recuperated from their heavy fighting earlier in the day. The charge quickly broke the battle lines of the Ottomans, who were already exhausted and demoralized and were now fleeing the battlefield in the face of the combined onslaught. Sobieski’s horsemen headed directly towards the Ottoman camps and Kara Mustafa’s headquarters, while the remaining Viennese garrison sallied out of its defenses to join in the assault. Mustafa knew the battle was lost but his will to fight remained undiminished. He tried to rally his forces to no avail. Only the argument that his own death would cause the destruction of the remaining Ottoman troops persuaded Mustafa to break off the melee. Seizing the Holy Banner of the Prophet and his private treasure, the Grand Vizier fled the battlefield in disgrace. When the battle was over and the Holy League was victorious, Sobieski paraphrased Julius Caesar declaring “Venimus, vidimus, Deus vicit.” We came, we saw, God conquered!

The battle for Vienna was a tremendous loss for the Ottoman Empire, which would never again seriously threaten the city. All told, the Ottomans suffered upwards of 70,000 killed, wounded, or missing between the siege and battle. The magnitude of the defeat was not lost to Kara Mustafa who sought to escape the Sultan’s vengeance by blaming his defeat on subordinate commanders, executing those that might inform the Sultan of the Grand Vizier’s mishandling of the Ottoman army. Mehmed IV remained unconvinced. Mustafa would pay for his failure. On December 25, 1683, in Belgrade, the sultan’s emissaries executed the Grand Vizier by strangulation and sent his head to Constantinople.

The Ottoman defeat at Vienna reversed four centuries of expansion and set the stage for the reconquest of Hungary and other lands in the Balkans by the Habsburg’s and their allies. The Ottomans would fight on for another 16 years, before being forced to sign the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699, which would cede much of Hungary to the Habsburgs.