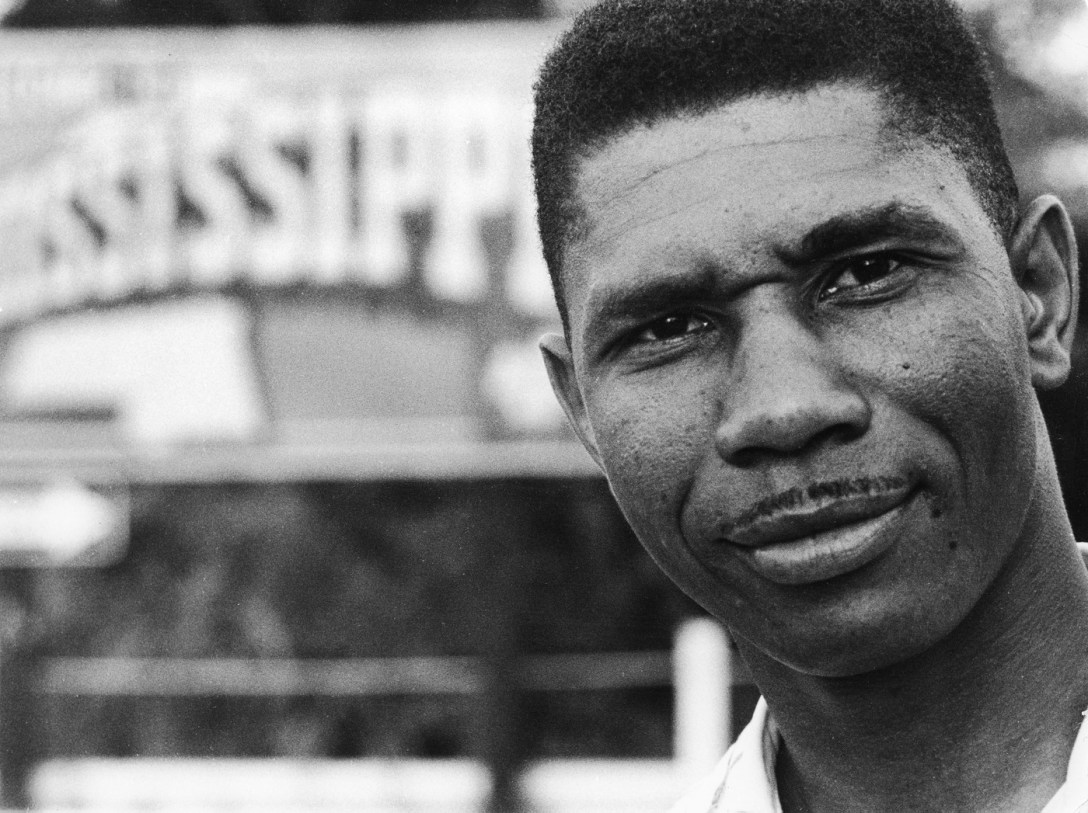

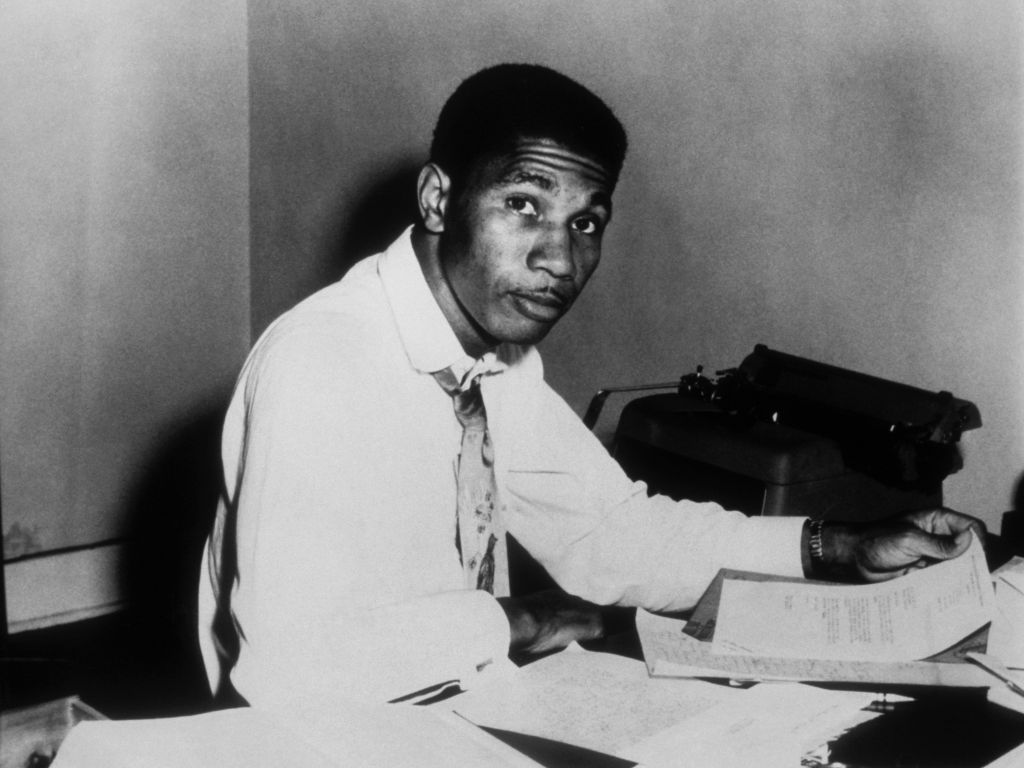

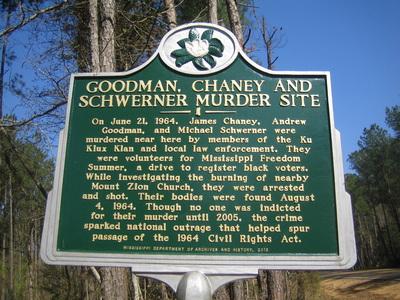

On June 21, 1964 three civil rights activist, Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney were kidnapped and brutally murdered by the Ku Klux Klan in Neshoba County Mississippi. The three were part of what was called Freedom Summer when hundreds of students and young civil rights activists descended upon Mississippi to register and educate the African-American population about their voting rights and to combat the state’s white supremacist power structure that disenfranchised blacks. The murder of Schwerner, Goodman, and Chaney would prove instrumental in the passage of the landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act the following year.

The project was organized by the Council of Federated Organizations, a coalition of the four major civil rights organizations — the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, the Congress of Racial Equality, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. The project set up dozens of Freedom Schools, Freedom Houses, and community centers in small towns throughout Mississippi to aid the local Black population.

Mississippi was chosen as the target of this effort because it had the lowest percentage of registered African-American voters of any state in the Union, only 6.7 percent of eligible black voters. Blacks had been restricted from voting since the turn of the century due to barriers to voter registration and other laws. Many of Mississippi’s white residents deeply resented these “outside agitators” and any attempt to change their ways. The Ku Klux Klan, the White Citizens’ Council, the Sovereignty Commission and even state and local law enforcement were engaged in a campaign of violence and harassment aimed intimidating these students and discouraging local African-Americans from cooperating with these outsiders. Schwerner, in particular, because of his work and “beatnik” appearance, attracted the attention of the Klan, which put him on their special hit list and gave him the code name “Goatee.”

On June 21, 1964, Schwerner, Goodman, and Cheney went to investigate the burning of the Mt. Zion Church in Neshoba county Mississippi by the Klan that served as a Freedom School. They were stopped by Neshoba County Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price just inside the city limits of Philadelphia, the county seat. Price, a member of the KKK who had been looking out for Schwerner or other civil rights workers, threw them in the Neshoba County jail, allegedly under suspicion for church arson. Price kept them in jail for seven hours till late in the evening, denying them a phone call, before he released them on bail. During this time he organized,a plan with his fellow Klan members to murder the activists. Price escorted them out of town on a lonely dirt road and directed never to return. Shortly after exiting the town limits they were chased down by the Klan, pulled over, abducted and murdered. Schwerner and Goodman were shot in the head. Chaney was beaten and castrated before being shot. Their bodies were buried in a newly constructed earthen dam just south of town.

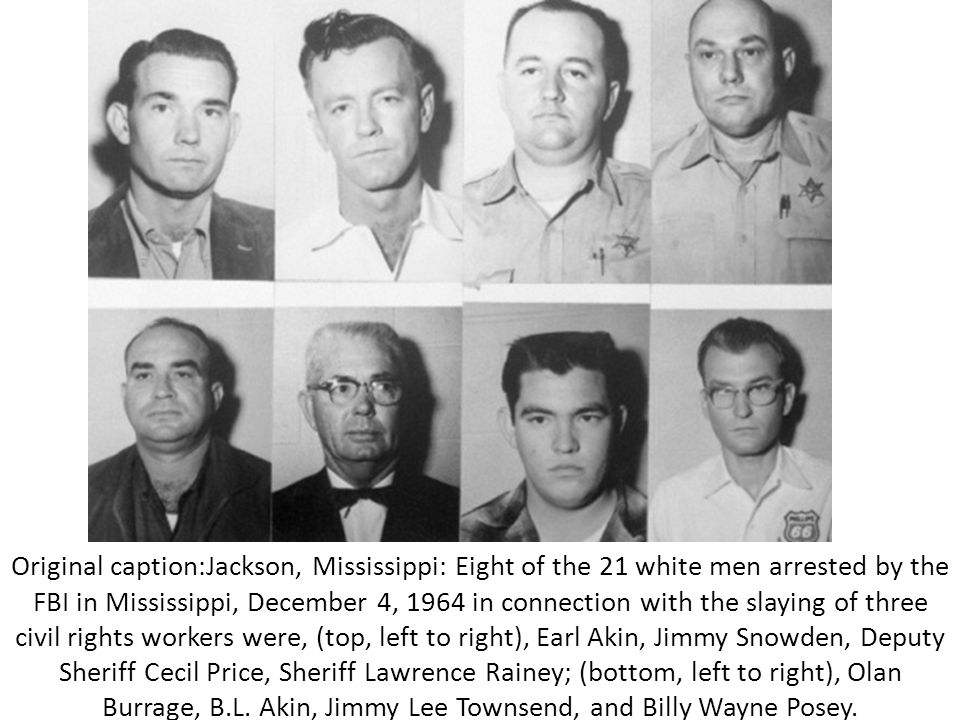

The ensuing FBI search for the three slain civil rights workers grabbed the attention of the nation and finally spotlight on Mississippi’s dreadful record on voting rights and the violent campaign against civil rights that was being waged in that state. On August 4, the remains of the three young men were found. The culprits were identified, but the state of Mississippi made no arrests. With the state unwilling to prosecute the case, nineteen men, including Deputy Price, were indicted on December 4, 1964 by the U.S. Justice Department for violating the civil rights of Schwerner, Goodman, and Chaney (charging the suspects with civil rights violations was the only way to give the federal government jurisdiction in the case). After nearly three years of legal wrangling, in which the U.S. Supreme Court ultimately defended the indictments, the men went on trial in Jackson, Mississippi. Three later an all-white jury found seven men guilty, including Price and KKK Imperial Wizard Sam Bowers. Nine were acquitted, and the jury deadlocked on three others. The mixed verdict was hailed as a major civil rights victory, as no one in Mississippi had ever before been convicted for actions taken against a civil rights worker. None of the convicted men served more than six years behind bars.

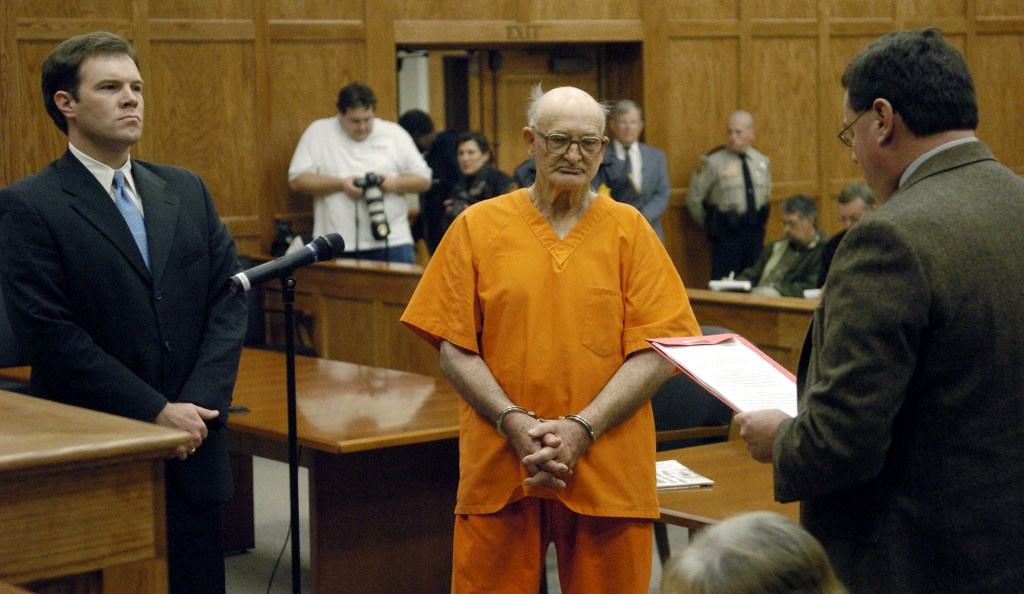

On June 21, 2005, the forty-first anniversary of the three murders, Edgar Ray Killen, was found guilty of three counts of manslaughter for his role in the case. At eighty years of age and best known as an outspoken white supremacist and part-time Baptist minister, he was sentenced to 60 years in prison. He died in prison on January 11, 2018, six days before his 93rd birthday.