On January 17, 1781, a combined force of Continental Regulars, dragoons, and militia, under General Daniel Morgan decisively defeated a British Army at the crucial Battle of Cowpens in the backcountry of South Carolina. It was a decisive victory that would boost American morale after the British capture of Charleston and the disastrous defeat at the battle of Camden. It also put in motion a series of events that would push the Redcoats northward culminating in their final defeat at Yorktown and the establishment of American independence.

The British Move South

After their crushing defeat at Saratoga in 1777 and the entry of the French into the war, the British faced the unsavory prospect of becoming bogged down in an increasingly costly war. To hasten a favorable end to the conflict, the British redirected their focus to the southern colonies. The rebellion was always the strongest in the New England and Mid-Atlantic colonies and the British Secretary of State for the American Department, Lord George Germain, believed that Great Britain could expand the war into the south with greater success and less cost by taking advantage of the large number of loyalists there.

In December 1778, the British seized Savannah, Georgia and eight months later repulsed a combined Franco-American effort to retake the city. After re-asserting their authority over Georgia, the British turned their attention to South Carolina. In May 1780, the British captured Charleston and 5,000 American soldiers after a six week siege. Seeking to roll back British gains, the Continental Congress dispatched General Horatio Gates, “the hero of Saratoga,” to command the remaining American military forces in the South, against the recommendation of General George Washington. Gates suffered a humiliating defeat in August at the battle of Camden, where he rapidly fled from the battlefield, leaving his subordinates behind to be taken prisoner.

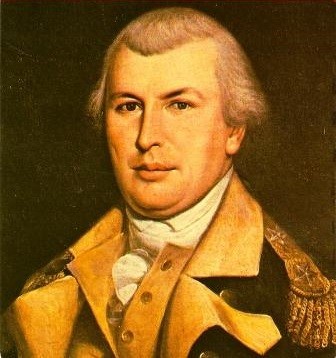

The British did indeed find strong support from loyalists in the cities and population centers of South Carolina like Charleston and Georgetown but they didn’t anticipate the strong resistance they encountered in the backcountry. In the wake of Gates’ defeat at Camden, irregular bands of militia fighters under men like Francis Marion, Thomas Sumter and Andrew Pickens emerged, engaging in hit and run tactics against loyalist and British military forces. In October 1780, General Washington appointed his most capable subordinate General Nathanael Greene, to replace Gates. Greene inherited what for all intents and purposes was a skeleton army and quickly set about trying to replenish its ranks. He placed key men as leaders in several states to secure supplies of all kinds and new recruits. He finally arrived in North Carolina to take command of his hastily formed army in December 1780.

War in the Backcountry

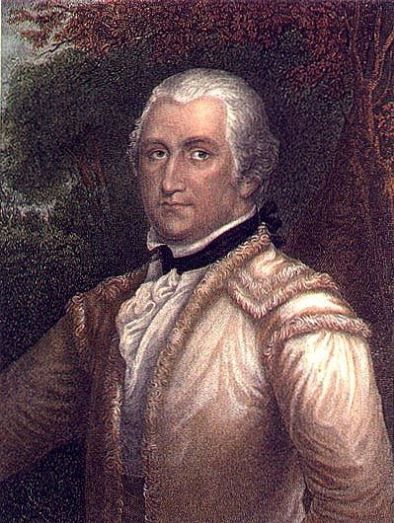

Greene made a bold decision to divide his small army into two. He sent a combined force of 300 Continental regulars and 700 militia under General Daniel Morgan to the western part of South Carolina where a brutal civil war was being fought between patriot and loyalist militias. Morgan, a brilliant tactician was tasked with hampering British operations in the backcountry and to bolster patriot morale. Believing that Morgan’s army was planning to attack the strategically important Fort Ninety Six, held by loyalist forces, British commander General Cornwallis sent the brash and despised cavalryman, Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton and his 1,100 Dragoons to destroy Morgan. Tarleton and his men were widely reviled. Shortly after the fall of Charleston, Tarleton and his men allegedly butchered a contingent of American soldiers under Colonel Abraham Buford who were trying to surrender at the Battle of Waxhaws. The incident would become known as “Bufford’s Massacre” and the subject of an intensive propaganda campaign by the Continental Army to bolster recruitment and incite resentment against the British.

British advance scouts located Morgan’s army on January 12, 1781 and Tarleton’s Dragoons doggedly hunted down the Americans. Morgan, ever the shrewd commander, continued to dodge a major engagement with the British until he could find favorable ground. On January 16, Morgan decided to make a stand at the Cowpens, a well-known crossroads and frontier pasturing ground.

Aware that the British were closing in, Morgan anticipated that Tarleton would conduct a frontal assault on his army the following day and proceeded to set a trap for the overly aggressive cavalry commander. He carefully positioned his forces into three progressively stronger defensive lines. The first consisted of select sharpshooters from Georgia and the Carolinas. Militia under Andrew Pickens constituted the second line. Continental Regulars from Maryland and Delaware made up the third and final line. That evening, Morgan explained the plan to his men. He wanted the militia to fire two shots before retreating and reforming behind the regulars. Morgan hoped his first two lines would slow and deplete Tarleton’s advance before his Contintenals dealt the decisive blow, a double envelopment.

Morgan Springs his Trap

The following day the battle went very much as Morgan had planned. Just before sunrise, Tarleton’s advance guard emerged from the woods in front of the American position and, as expected, he ordered the small group of Dragoons to drive the American skirmishers back. Shielded by trees and other natural obstacles, the American sharpshooters picked off a number of Tarleton’s Dragoons forcing them to retreat. Upping the ante, Tarleton deployed his infantry forward to clear out the skirmishers , who then fell back and joined the second line of militia as planned. The infantry pressed forward and ran into Morgan’s second line consisting of Andrew Pickens’ militia. From there, the Americans, delivered two deadly volleys, thinning the British ranks, before retreating.

After driving back two successive lines of militia, Tarleton believed the Americans to be in full retreat. In the hope of delivering a coup de grace, Tarleton sent forward the 17th Dragoons in a mounted charge. Watching the cavalry advance, Morgan ordered his own dragoons, under Lt. Col. William Washington to meet the attack. Washington and his men charged forward and beat back the British horsemen.

Tarleton finally committed his reserves and sent the 71st Highlanders forward. Instead of facing more militia, they encountered a third and final line composed of Continental Regulars from Maryland and Delaware, who were some of the best trained and most disciplined soldiers in the entire Continental Army. They unleashed a powerful volley which brought the enemy advance to a grinding halt. Morgan subsequently launched a counterattack. In a double envelopment, the Continentals slammed in Tarleton’s center with bayonets while Pickens’ militia and Washington’s horsemen struck the British flanks simultaneously. Tarleton’s line crumbled and what was left of his command fled from the field. The battle was over in less than an hour. It was a complete victory for the Americans. British losses were staggering: 110 dead, over 200 wounded and 500 captured. Morgan lost only 12 killed and 60 wounded.

Aftermath

The Battle of Cowpens proved to be a turning point in the War for Independence in the south, one that would eventually lead to Cornwallis’ surrender ten months later at Yorktown. In the months following the battle, Greene and Cornwallis’ armies clashed in a number of battles in which the Americans were driven from the field but only at great cost to the British. Greene best summed up this dynamic declaring, “We fight, get beat, rise, and fight again.” Greene’s strategy of “bleeding” the British would culminate in the Battle of Guilford Courthouse where Cornwallis was victorious but only at the expense of one-third of his force and some of his best officers. Watching his army wither away, Cornwallis opted to withdraw to his supply base at Wilmington to rest and refit. With his army still not in a condition to engage Greene by the middle of April, Cornwallis decided to shift his operations and began moving north to Virginia, a decision that would eventually lead to his demise at Yorktown.